Why the Perception of Indigenous Art is Changing

Exhibitions at Tate Modern and Fondation Opale, and Frieze Week presentations of artists by Tony Albert, Makinti Napanangka and Robyn Kahukiwa signal a decisive shift

Exhibitions at Tate Modern and Fondation Opale, and Frieze Week presentations of artists by Tony Albert, Makinti Napanangka and Robyn Kahukiwa signal a decisive shift

‘This is not just a pretty picture or a nice story’, said the Yolŋu artist Naminapu Maymuru-White in an interview about the works she was making for last year’s Frieze London. ‘This is the truth. This is our reality.’ The reality of indigenous artists – including Aboriginal, First Nations, Māori and Torres Strait Islander people – is something which visitors to UK galleries and museums this year will increasingly encounter for themselves.

In London this October, Indigenous Australian works will be shown by Australian gallery Sullivan+Strumpf at Frieze London and D'Lan Contemporary at Frieze Masters. Concurrently with the fairs, Tate Modern will be showing a survey of Emily Kam Kngwarray: the first large-scale exhibition of the late artist’s work ever to be held in Europe. An iconic figure in twentieth century Australian art, Kngwarray was an Anmatyerr woman, who spent her life entirely in the Sandover region of Australia’s Northern Territory, though her reputation expanded far beyond: in 1993, she was one of three artists to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale.

Beginning her career late in life — she completed over 1,000 after the age of 70 — Kngwarray began painting in batik, then moving to canvas. Her works are prized by advocates of Indigenous Australian art, including the actor Steve Martin, who has lent several pieces to the Tate exhibition. In 2017, her work Earth’s Creation I (1994) achieved approximately $1.3 million at auction: then the second ever highest price reached by an Aboriginal artist. This year, her estate joined the roster of Pace Gallery.

The Tate’s Kngwarray retrospective, which originated at the National Gallery of Australia, is indicative of the institution’s recent emphasis on supporting Indigenous artists from across the globe. This year’s Hyundai Commission in the Turbine Hall has been awarded to Sámi artist Máret Ánne Sara, whose work draws on her family’s heritage of reindeer herding in northern Norway. During the 2024 Venice Biennale – which featured Australian First Nation artists including Marlene Gilson and the Māori Mataaho Collective, who received that year’s Golden Lion – Tate’s Maria Balshaw announced to a crowd in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco a four-year commitment to increase its holdings of Indigenous art, supported by the AKO Foundation. Sixth months later, Maymuru-White’s works were among the acquisitions the Tate made at Frieze London via the Tate Endeavor Fund, adding to the national collection a series of 17 paintings in natural pigments on bark, exhibited in a display supported by Breguet and curated by Jenn Ellis.

Calel’s The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge (‘Ru k’ ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el’, 2021) — an evolving installation of stones and fruits — from Proyectos Ultravioleta at the 2023 edition of Frieze London. In an historic first, the institution agreed to be custodians, rather than ‘owners’ of the work, for a 13 year term, including a commitment to support a Kaqchikel cause of Calel’s choice.

But Tate Modern is far from the only UK institution platforming Indigenous art in this moment: this summer, the Camden Art Centre in London is exhibiting the first institution exhibition in the country of Duane Linklater, an Omaskêko Ininiwak artist from Canada; at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Galery, the first international exhibition of Santiago Yahuancari – artist, activist and leader of the White Heron clan of the Uitoto people, based in northern Peru – is on view until January 2026, before travelling to Sao Paulo and Mexico City. Among Yahuancari’s often astonishing mythological and historical panoramas, the exhibition features a video by the artist’s son, Rember Yahuarcani, whose own work will be featured at Frieze London by Josh Lilley, alongside a solo show at the gallery’s London space. Also concurrent with Frieze London, fair exhibitor Phillida Reid will present at the gallery an historic exhibition of works by Aotearoa New Zealand artist Robyn Kahukiwa. Put together with Kahukiwa before her death in April this year, this will be the artist’s first exhibition in London in over a quarter century, comprising works loaned by public and private collections alongside pieces newly shared by her estate. Spanning three decades of painting and drawing, it offers a chance to encounter one of the prominent Māori artists in New Zealand in a vivid new light.

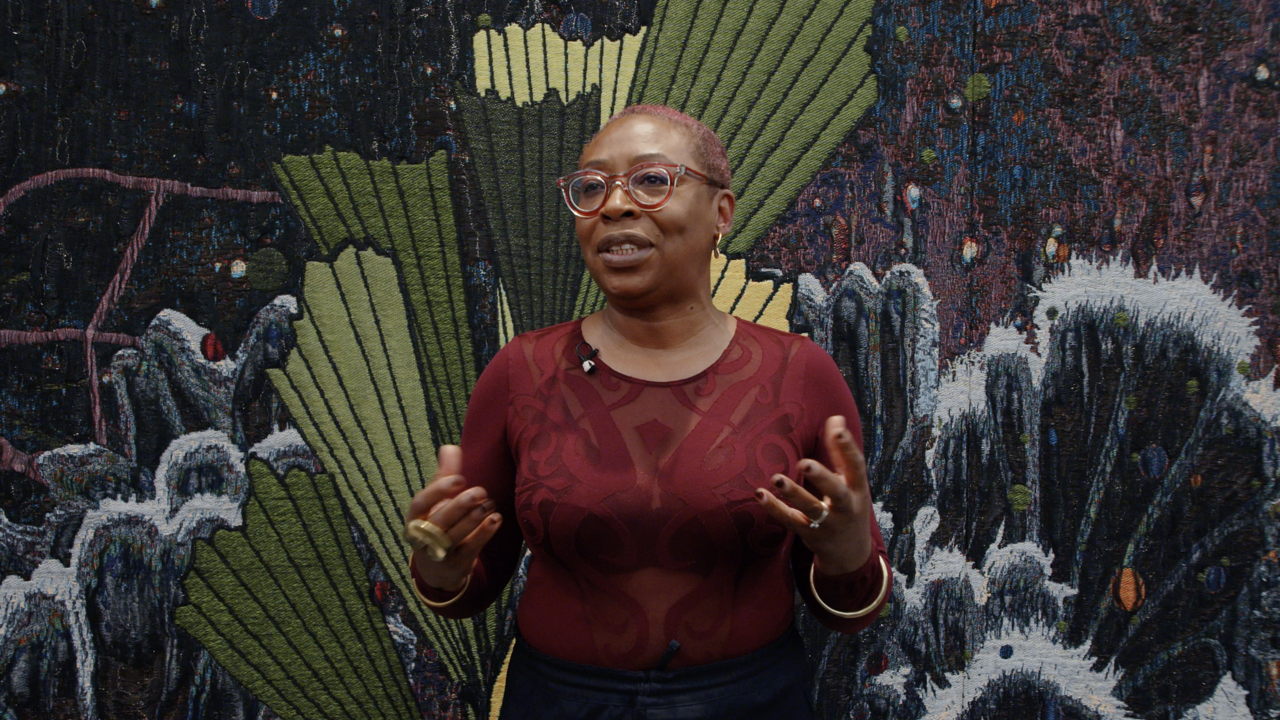

For Ursula Sullivan of Sullivan+Strumpf, the burgeoning presence of Indigenous artists in such settings parallels a psychological shift among collectors. ‘I think there's a change that is happening’, she says, ‘where it's like “my American or European or British or whatever view is not the only view and I’m open to other stories. I’m open to other ideas”’. Mounting a show at Frieze’s No. 9 Cork Street in 2023, she says ‘we wanted to sort of bring something from different parts of the world’ – which included Samoan-Australian artist Angela Tiatia and First Nations artist Gunybi Ganambarr, who works from the extremely remote Gängan homeland. ‘There was a sense of discovery’, she adds, with visitors to the show acquiring work for collections in London, Europe and the Americas. ‘It was really quite something for us to see, coming from Australia, where we don't necessarily always get that audience, even online. So that certainly changed things for these artists.’

Drawing on centuries of collective memory, Indigenous Australian art has long been treated as something of a specialist subject, with some collectors focussing on supporting the artists from a particular art centre, such as Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, where Maymuru-White works. Introducing the work to new audiences, Sullivan says, meant ‘we had to do a lot of talking and a lot of explaining and a lot of opening people's eyes.’ But what helps span this cultural difference, she believes, is both the materiality of the work - paintings on bark, she notes, are ‘something that's different to what people might already have’ – and the universality of its themes. ‘The stories that a lot of Indigenous artists are talking about are stories that are really universal’, Sullivan reflects. ‘Particularly with Naminapu, there's birth and deaths […] how when we pass, we go up into the stars, and then we're with our family.’ Recently, sales of the artist’s work have been made to a private museum in Indonesia, and collectors in Singapore. For Sullivan, the Tate acquisition from Frieze London cements the ‘real desire to see it is contemporary.’

What is changing, then, is perception. The French-born, Switzerland-based collector and patron Bérengère Primat tells me that when she began her journey, ‘Aboriginal art was often viewed through an ethnographic lens, as something separate from contemporary art.’ For Primat, the transformative moment took place in an exhibition in Paris in 2002, showing works from the collection of dealer Arnaud d’Serval. ‘I remember walking into that space and being instantly captivated—the works radiated a depth and energy that felt almost tangible. It was not just an aesthetic experience; it was visceral, like stepping into another way of seeing and understanding the world.’

Primat set herself the mission of understanding the art on its own terms, travelling to Australia to visit art-making communities, and spending time with artists and their families: ‘witnessing firsthand the connection between art, Country, and ancestral memory.’ ‘I listened to stories, learned about Country and the Dreaming, and let the works themselves guide me.’ She also read, citing writings by Aboriginal Australians Marcia Langton and Hetti Perkins, among others, as key sources. What emerged from the research was a recognition of ‘how profoundly contemporary and innovative these works truly are, even while being rooted in ancient traditions.’

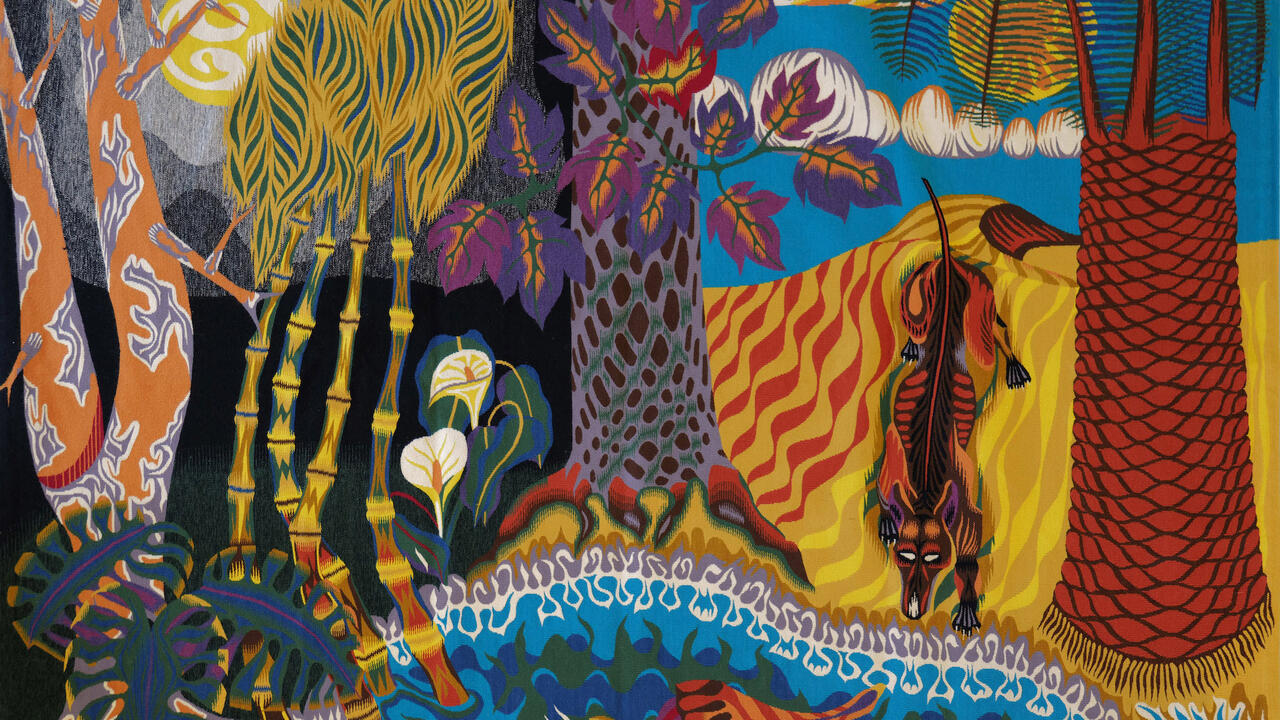

In 2018, she established in Lens, Switzerland Fondation Opale: Europe’s only art centre dedicated to Indigenous Australian art. A private, non-profit foundation, funded primarily through Primat’s own resources, it is testimony to its founder’s singular drive and focus. Aiming to ‘present Aboriginal art as a living and evolving contemporary practice’, in Primat’s words., its exhibition programme has variously explored themes such as music and absence, considered the influence of Indigenous Australian artists on the work of Yves Klein, or examined the activity in one community in a single year (‘Papayuna, 1971’). A particular hallmark of these exhibitions has been the dialogue between Aboriginal artists and those from other traditions: for example, this summer’s brilliantly conceived pairing of Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori and visionary American painter Forrest Bess, entitled ‘Beneath the Reflections of the World’. When I ask why this has proven such a focus, she replies: ‘Because they break down artificial boundaries.’ ‘Aboriginal art has too often been seen as “other,” when in fact it speaks to universal themes’. Including, say, a Pipilotti Rist video installation alongside ancient works from Arnhem Land, in ‘Before Time Began’ (2019-20), ‘highlights these shared questions while respecting the distinctiveness of each voice.’ In this way, Primat hopes, the programme ultimately ‘challenges audiences to reconsider their assumptions about what contemporary art is and where it comes from.’

Primat is a lender to the Tate’s Kngwarray exhibition, which she recommends ardently as ‘a truly remarkable retrospective […] a powerful insight into the evolution and depth of her practice.’ The opening, she notes, was a special moment, bringing together a community of the artist’s collectors, admirers, colleagues and kin. ‘It felt like a gathering of her world,’ she observes. An iteration of the retrospective will travel to Fondation Opale in 2026.

For those curious to explore contemporary Aboriginal Australian art more deeply, presentations at the fairs offer an excellent point of entry. At Frieze London, Sullivan+Strumpf’s stand will include works by Maymuru-White as well as new work by Tony Albert. Raised ‘off land’ in Brisbane, Albert was a founding member of the urban-based Indigenous collective ProppaNOW, and his work often explores the engagement between Aboriginal people a white majority society. Showing at Frieze London, Albert’s work plays with the legacy of Margaret Preston, a white Australian artist who championed Indigenous Australian art, adapting and appropriating it into her own modernist language. Sourcing examples of Preston’s work that were reproduced s kitsch home décor or tourist souvenirs, Albert combines them into his own compositions, exemplifying the complex tensions of what he calls ‘Aboriginalia’.

Meanwhile at Frieze Masters, D’Lan Contemporary will dedicate their stand to Makinti Napanangka and Naata Nungurrayi, who were deeply influenced by Emily Kam Kngwarray, and who began painting the year she passed. Founded in 2016 by D’Lan Davidson, a former Sotheby’s head of Aboriginal art, D’Lan Contemporary operates spaces in Melbourne, Sydney in New York. The first Australian gallery to exhibit at Frieze Masters, last year their presentation of Goowoomji Nyunkuny Paddy Bedford saw 13 sales on the fair’s opening day, netting some $1.3 million.

What will continue to turn the dial for collectors new to this area of contemporary practice? ‘I think you buy it because you understand and accept and appreciate what you're acquiring’, Sullivan suggests. After a pause, she adds: ‘there's a real heart in collecting this work.’

Sullivan+Strumpf and Pace exhibit at Frieze London

D'Lan Contemporary exhibit at Frieze Masters

‘Robyn Kahukiwa’ is on view at Phillida Reid, London from 19th September to 1st November

‘Rember Yahuancari:: Here Lives the Origin’ is on view at Josh Lilley, London from 16th October to 20th November

‘Beneath the Reflections of the World’ is on view at Fondation Opale, Lens until 16th November

‘Santiago Yahuancari: The Beginning of Knowledge’ is on view at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester until 4th January 2026

‘Emily Kam Kngwarray’ is on view at Tate Modern, London until 11th January 2026

Main image: Installation view, ‘Beneath the Reflections', Fondation Opale, 2025. Photo: © c-lumento