Artists Rally Against ICE in Los Angeles

As the US crackdown on migrants continues, Los Angeles’s activists and artists are responding to the threat to their communities

As the US crackdown on migrants continues, Los Angeles’s activists and artists are responding to the threat to their communities

In the early 2000s, artist Anabel Juárez moved from the Mexican state of Michoacán, where she was born, to Los Angeles County. Then 15 years old, she reeled from the cultural changes accompanying her new life. ‘I didn’t speak the language right into high school,’ she tells me in a recent conversation. ‘I had to adapt to a new place, to a new language, to new everything.’ During that fraught time, Juárez found some solace in seeing ‘a lot of familiar faces in terms of other people who were also migrants at school, around the neighbourhood’.

When Juárez later began working with ceramics, she felt drawn to crafting intricate leaves and buds in her pieces. She moulded huge slabs of clay into spindly, bright sunflowers; her flowerpots brimmed with a confluence of native Californian plants and migrant varietals that had taken root and flourished. Culling from stories told by her father, a lifelong gardener, Juárez reflected on how the natural life cycle of plants related to her own experience as a migrant, specifically in ‘what it means to adopt a new land’. Her floral pieces are sometimes interspersed with objects, like a single gardening glove, symbolic of the oft-invisible migrant labour that goes into maintaining the elaborate floral displays and immaculate lawns of Southern California: ‘I would see flower vendors showing up for work in the morning,’ she says, ‘and I would go home late at night and they would still be out working.’

Juárez has been making ceramic pots and flowers for many years, some of which she exhibited at Anat Ebgi in 2025; she will be showing again at Frieze in 2026. Her works, along with those of other LA artists who have long dealt with topics of migration and labour, have taken on a weightier significance following brutal crackdowns by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) ramping up since summer 2025 across the city. ICE raids have resulted in thousands of people – many of them migrants from Central America – being imprisoned in detention centres; a recent ProPublica report found that ICE had detained nearly 200 US citizens in raids. The detainment and deportation of some immigrants have been so shrouded in secrecy that neither their families nor their attorneys even know where they are, let alone how to reach them.

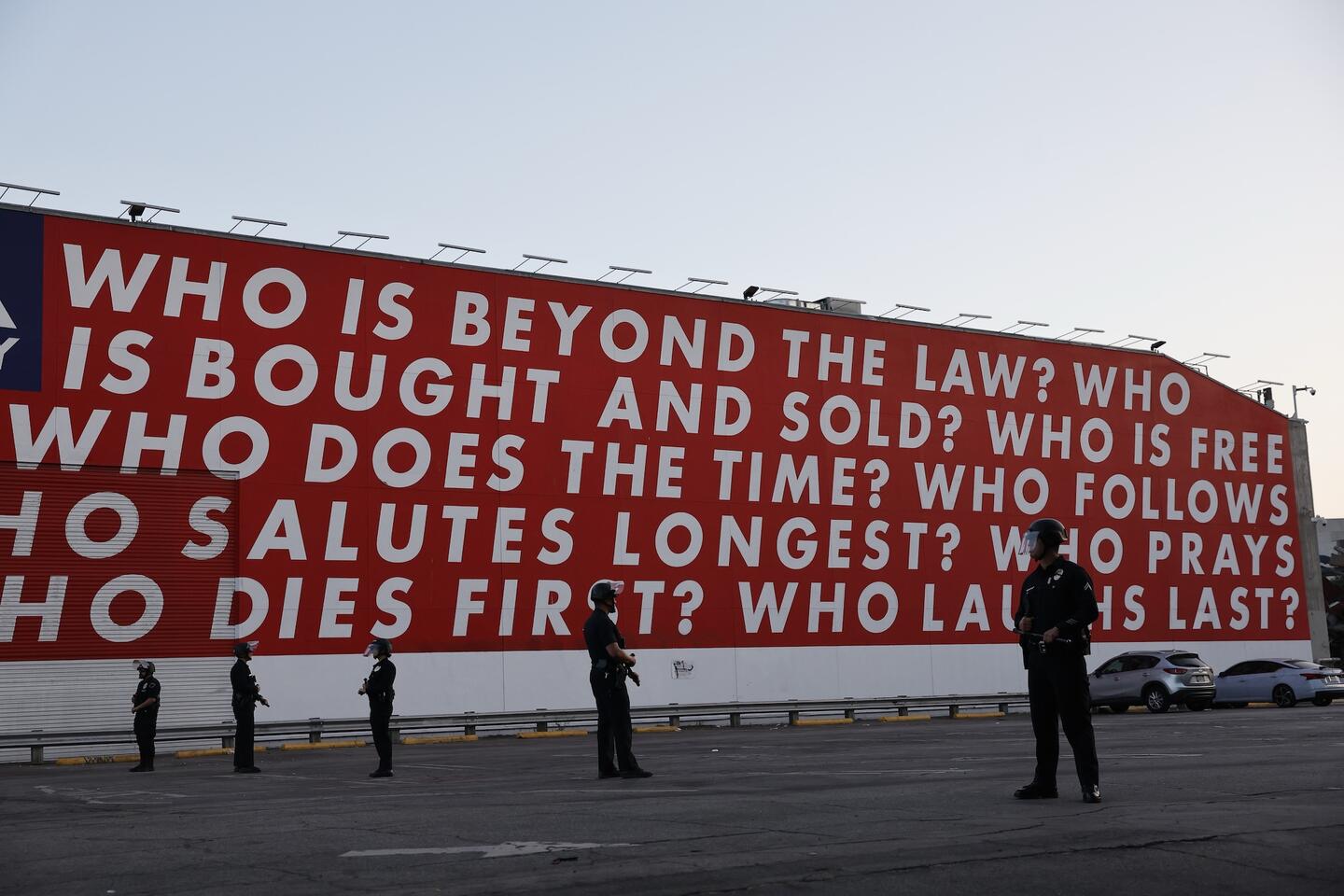

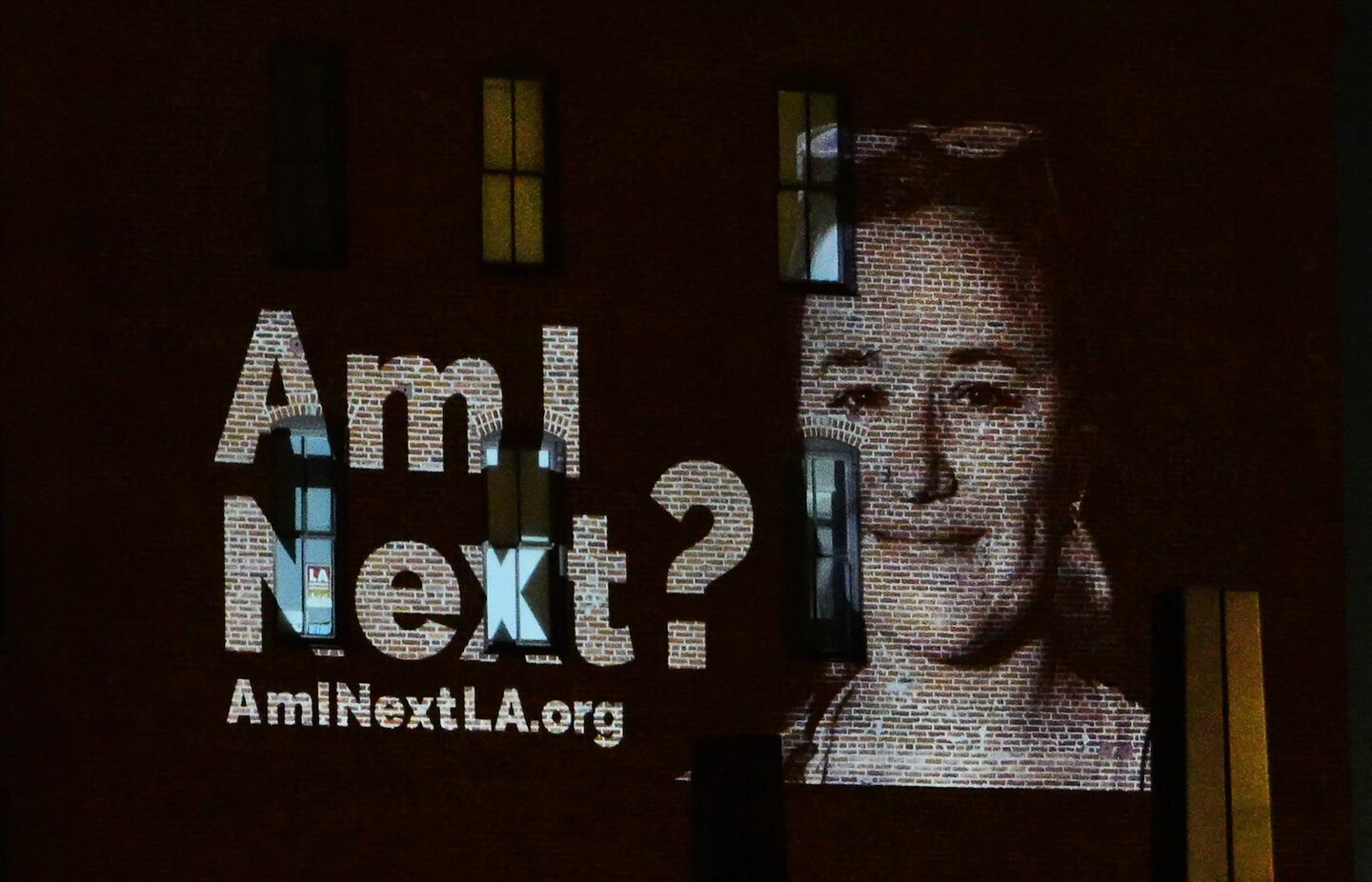

In response, Angelenos took to Downtown streets in protest. During these demonstrations, one particular sign became a familiar sight and a rallying cry: an image of a teal-and-white neon spelling out ‘DEPORT ICE’. The LA-based artist Patrick Martinez created the orginal neon sign back in 2018, but during the protests this past summer, he began making and selling prints of it, with proceeds going to organizations that help protect immigrant rights. ‘I’m consistently putting these messages out there,’ he says when I speak to him. ‘People are getting deported in large numbers now. The brutality of what’s happening on the streets of Los Angeles and other places in America is overt, and it’s here to send a message.’ Martinez considers his neon protest works as ‘warning signs’ to cut ‘through the fog and the haze of all this confusion’.

Martinez, whose work is featured in the campaign for this year’s fair, considers himself as both a landscape painter and an archivist. He has been threading documentation of recent ICE raids into his ongoing ‘Pee-Chee’ series; previously, he has immortalized the victims of police brutality in his riff on the school stationery staple; now, the LAPD officers have been replaced by ICE agents. ‘I want to cement these happenings, because the images get lost in news reports or social media,’ says Martinez of these recent works. Like Juárez, Martinez has long spotlighted immigrant rights in his work. ‘This is the type of work that I’ve been making, and I’ve been pretty urgent about it,’ he explains. ‘It’s just more amplified now.’

I want to cement these happenings, because the images get lost in news reports or social media.

Since early summer, constellations of local communities, individual artists and collectives have sprung into action to help protect immigrants, with groups including Art Made Between Opposite Sides (AMBOS), which fosters advocacy on both sides of the US-Mexico border through art initiatives, and which has created activations at Frieze in the past, distributing crucial materials with mutual aid networks. Others have organized rotating ‘ICE watch groups’ to keep an eye on locations where raids tend to happen, such as restaurants and Home Depot parking lots. Longstanding institutions like Self-Help Graphics & Art have printed ‘Know Your Rights’ cards to distribute. In July, photographer Thalía Gochez organized an exhibition, ‘The Land Will Always Remember Us’, at Mid-City’s Amato Studio. It showed Latino artists’ work and bouquets made by Doña Sylvia, Gochez’s flower vendor, who had stopped working out of fear. When Jorge Cruz, a fruit vendor who often made the rounds of gallery openings and who participated in Ruben Ochoa’s project at Frieze LA in 2023, where he sold fruit from a custom-designed cart, was at risk of deportation in the fall, the art community rallied around him.

With this heightened attention, some artists have had to adjust their traditional modes for disseminating work. Tanya Aguiñiga, the founder of AMBOS, says that the organization has been shifting its operations in response to the ICE clampdown. ‘We have to be more discreet about stuff and sadly just more distrusting of opening things up to everybody,’ she tells me. ‘We have to make sure that we can protect the most vulnerable communities.’ Even the way some artists’ work is received has changed: earlier this year, an AMBOS installation created with migrants at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University in Malibu, which included a fabric strip with the words ‘Abolish ICE’ and ‘Save the Children’, was censored. Without an explanation to the artists, the piece of fabric was hidden from public view, says fellow AMBOS member Natalie M. Godinez. She points out that the same piece was commissioned by the Hammer Museum for the 2023 ‘Made in LA’ biennial, an exhibition that seems like a lifetime ago, considering ‘how different the political landscape is from then to now’, she says.

In Godinez’s view, more can be done beyond vital grassroots mutual aid work and individual actions, especially from local institutions capable of accommodating sanctuary spaces. ‘I wish some of the bigger museums would have responded in that way, just because they have the resources and the space,’ she said during our recent conversation. ‘There’s always more that we could do,’ Martinez adds. ‘But, having said that, I think that the current administration has done its job of scaring people, and art is the same. Everything’s in peril right now. I think that museums are in the same position, where they are probably scared of getting attacked, so I understand. But we have to find a middle ground.’

Amid the uncertainty, artists like Juárez are continuing to make work as they always have with the same goal in mind: to honour immigrants. ‘When I began making these works, it wasn’t really as a response to the current environment and atmosphere,’ she says. ‘It’s really me reflecting on migration and resilience, and it comes from my own lived experiences as someone who migrated, as someone who is living in this community, and these people being afraid. But also – in spite of being afraid – still showing up to work. Because we have to, right?’

This article first appeared in Frieze Week Los Angeles 2026.

Further Information

Frieze Los Angeles 2026, 26 February – 1 March 2026, Santa Monica Airport.

Limited early-bird tickets are available now, or become a Frieze Member for priority access, multi-day entry, exclusive guided tours and more.

For all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to the newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram and Frieze Official on Facebook.

Main image: Protestors carrying signs designed by Patrick Martinez, Los Angeles, 2025. Photograph: Patrick Martinez