Up Close

Fair exhibitors discuss exceptional pieces they will show at Frieze New York 2017

Fair exhibitors discuss exceptional pieces they will show at Frieze New York 2017

Behind every artwork is a story or two, and the gallerists often tell them best. Caroline Roux quizzed nine exhibitors about some exceptional pieces they will show at Frieze New York 2017...

The London dealer Bernard Jacobson has devoted much of his career to Robert Motherwell (1915–1991). Carefully acquiring works by the American artist since 2003, Jacobson has also written the man’s biography. The latter was no easy feat: Motherwell was the original force behind the New York School, a prolific writer, generous teacher (Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly were among his many students at Black Mountain College), and married four times. His complete oeuvre includes 800 collages and 500 prints and hundreds of paintings.

This one, until five years ago in the collection of Norman and Irma Braman, is number 163 from the ‘Elegy for the Spanish Republic’ series, which the artist began in 1948 and continued up to his death. In this series, Motherwell continually returns to the image of the dead bull (in black, for mourning): a motif to suggest the power and brutality of the Spanish Civil War. “Motherwell’s is a complex story,” says Jacobson. “And this is a great part of it.”

The American artist Robert Morris (b.1931) began making felt works like Untitled (1967) in the late 1960s, though few are in circulation, making this a rare sight at an art fair. “He had an exhibition of felt works with Leo in 1968,” says legendary dealer Leo Castelli’s widow Barbara Castelli, “that travelled to Sonnabend in Paris and Sperone in Turin, this piece was on the invitation for the latter,” she adds. Morris found more appreciation in Europe than in his home country, so while some felt pieces sold, others never made it back to New York. “They were just destroyed,” explains Castelli, “the artist and the gallery felt they were doing something important, but they didn’t worship the objects themselves.” Trailing to the floor, this dense piece is an investigation of weight, made with heroic purity from a single piece of material. The gallery is presenting Untitled at the fair with a sound work by Keith Sonnier (b.1941), not seen since its exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1970, in which two microphones placed near to one another create interference: a deft pairing of broadcast and absorption.

The late Carol Rama (1918–2015) was a self-taught artist with a fearless streak, who began her career with paintings that were erotic, obsessive and often branded obscene by the government of 1940s Italy, where she lived. In 1945, one of her shows in Turin was closed down by police.

Over the ’50s, she moved away from the gurative depictions, making works with no less restless energy, but fewer grounds for censorship. These incorporated a number of three-dimensional elements, from syringes and pieces of glass to bicycle tires – her favoured material of the ’60s. The poet and writer Eduardo Sanguinetti gave such works the name ‘Bricolages’. This striking example from 1964 includes beads, curled metal shavings, nail polish and oil paint on a Masonite ground. Regardless of the materials, it is Rama’s extraordinary sensitivity to composition that prevails.

Tickets for Frieze New York 2017 are available here.

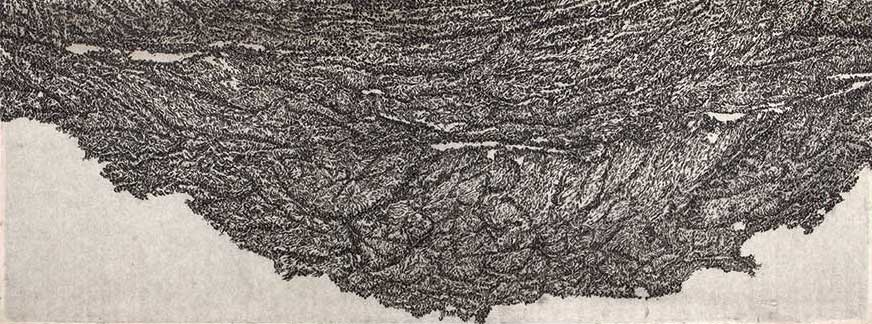

Since the late 1960s, Giuseppe Penone (b.1947) the Italian artist responsible for Palpebre (‘Eyelid’) (1990), explored the relationship between man, nature and art. He’s now best known, perhaps, for large-scale sculptures of trees in bronze and wood which reveal the similarities between them and the human body – skin becomes bark, limbs branches, the torso the trunk. His earlier career also involved resonant live works, some in which he was the protagonist, others where through his interventions living trees became the performers.

Other strands of practice relate more subtly to the body, such as the Palpebre (‘Eyelid’) series, begun in 1975. For these, he sprinkled resin onto his eyelids, and took away an imprint of it with adhesive tape. This he then photographed, projected onto paper, and transcribed it in pencil and other materials. The result, as in this example from 1990, is a delicacy and intimacy – despite its three and a half meter span – where the act of drawing by hand brings the work back to the body itself. At the fair, it assumes place in a presentation dedicated to the Arte Povera with which Penone is associated.

“He’s the grandfather of American colour photography,” says Greg Lulay of William Eggleston (b. 1939). Of this image from ‘The Democratic Forest’ series, Lulay explains “the images are rich on a visual and narrative level – here you have a view of America, Pop Art references in the signs, and the color blocking which moves to abstraction.”

The photograph was taken in Memphis where Eggleston, now aged 78, still lives. The series to which it belongs, made between 1983 and 1986, is a huge body of work, in which Egglestone treats every subject – whether mundane, curious or magnificent – with the same measured eye. “There is no subject matter that’s central or more important,” says Lulay; instead, “the framing is everything.”

Some of these images have only been published in books, or not yet reproduced at all. While Eggleston historically chose to work with the dye transfer process for the intense saturation of colour it provided, the technique is no longer available, so the artist has turned to printing with pigment-based inks, which allows for larger formats. Eggleston, is still carefully selecting works to be presented in this technique, and thus shown for the first time – this is one of his choices.

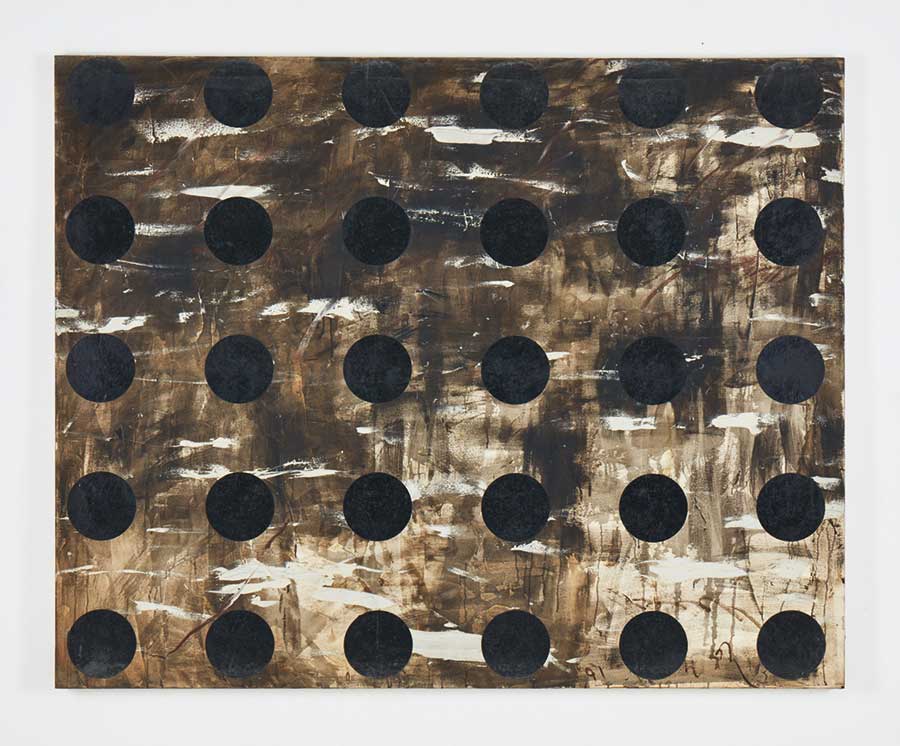

Kim Yong-Ik (b.1947) was studying forestry at an agricultural college when, one December night in 1967, he realized he was on the wrong path. A year later, aged 21, he was enrolled in Hongjik University in Seoul, and on his way to becoming an artist. Ever since, Kim has striven to work outside of any prevailing group or genre: not least the modernist movement which has dominated Korean art practice in the 1970s. The artist claims that his persistently questioning and independent stance has even affected his physical and mental health, so Diana Kim of Kukje Gallery tells me.

In the early 1990s, Kim began a series of Polka Dot paintings, including this Untitled from 1991. In these works, Kim takes the most perfect geometric form, the circle, and creates rigorous arrangements, before corrupting the painting with dust and stains and occasional scribblings of his own thoughts. It’s a critique of Modernism and its perfectionist ideals, and a compelling one at that.

Tickets for Frieze New York are available here.

Frontally orientated, but projecting into space, Lynda Benglis’s (b.1941) Swinburne Egg I (2009) has a hybridity that reflects the memory of the body in motion. The body plays a key role in Benglis’s art, as any who remember her iconic 1974 Artforum advert will know; here, the physicality of the work evinces the artist’s tactile engagement with wire and foam, from which a cast is taken. The contradiction felt between the hard permanence of the material and the eetingness of the bodily gestures that determined the work’s form lends it an entrancing indefinability: as Ellen Robinson notes, it’s hard to say if such works “are light or heavy, soft or hard, fugitive or stable.” Emphasizing this instability, Robinson quotes Benglis’s own comments on the series: “the way the light comes through in the middle, from beneath the surface, makes them very eerie and alive. And that light changes according to different conditions of light, whether natural or artificial”.

Though Exposed Prosthetic (2016) is just a few centimeters high, Ron Nagle (b.1939) “makes tiny things invested with the majesty of the Taj Mahal,” as critic Dave Hickey has written. Starting to work with clay in high school, Nagle trained with Peter Voulkos, and today holds a place with Voulkos and Ken Price as one of the major postwar American ceramicists. The piece belongs to a body of work intended to be seen from above, or in the round. Nagle often speaks of his works of as three-dimensional paintings: the still lifes of Giorgio Morandi, encountered at the Ferus Gallery, have been a lasting inspiration. A similar dedication to the intimate study of form is apparent in this work, despite its arresting artificial colors (a legacy of Nagle’s interest in California hot rod culture, through which he also learned to spray paint). Nagle’s original gifts extend beyond his distinctive handling of colour, form and texture: a sometime musician, in 1973, he made sound effects for ‘The Exorcist’, including trapping bees in jars. A similar sense of controlled energy can be felt in this work.

That Marcius Galan (b.1972) once studied architecture is apparent in Erased composition (green 15) (2014): the São Paolo- based artist “is fascinated by space and how it defines our behavior,” says Galeria Luisa Strina’s Maria Quiroga, noting one work at Brazil’s Inhotim sculpture park which conjurs the illusion of a glass wall across the corner of a room. “He’s interested in urban planning and diagrams and systems derived from economics or geography, and then he tries to disrupt them,” she adds. Galan’s work with erasers began in 1999, when he started accumulating the colorful residue from rubbing out drawings to create new ones. He recently returned to the idea, this time developing a visual system from the reduction of the erasers themselves, as here. This gradual consumption is another of the artist’s preoccupations, linking him to many Brazilian forebears. “We have always been interested in Concrete art in the gallery,” Quiroga adds “Marcius continues that story.”

Tickets for Frieze New York 2017 are available here.