Edward Krasiński

Bunkier Sztuki, Kraków, Poland

Bunkier Sztuki, Kraków, Poland

‘ABC’, the recent exhibition of works by Edward Krasiński, curated by Andrzej Przywara for Bunkier Sztuki, a municipal gallery of contemporary art in Kraków, is the long-awaited homecoming of the artist, who passed away in 2004 at the age of 79. The first survey show in Poland after the artist’s death and the first large exhibition since the 2004 retrospective at Generali Foundation in Vienna, ‘ABC’ ranges from Krasiński’s early paintings and drawings to his late installations, but also a vast array of documents uncovered through arduous research – exhibition plans and models, documentary films and photographs, manuscripts of the artist’s aphorisms (such as ‘I was born when I wasn’t yet’) – even a one-inch-long piece of perforated telex tape with the word ‘blue’, which Krasiński sent to the 1970 Tokyo Biennial 5,000 times as an emergency replacement for his signature blue tape strip, which was delayed in transit by sea.

During World War II Krasiński studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in occupied Kraków, and after the war he attended the Academy of Fine Arts. His professors were Polish Post-Impressionists (colourists) and Symbolists, but he socialized with a younger bohemian crowd: late-avant-garde painters, book and magazine illustrators, stage designers, actors, writers and photographers. In 1965 the 40-year-old artist held his first solo exhibition at the now defunct Krzysztofory Gallery, a dark cellar with vaulted ceilings and brick walls, at that time the showcase of local Modernists. By then Krasiński had been living in Warsaw for ten years, where in 1966 he became one of the founders of the Foksal Gallery.

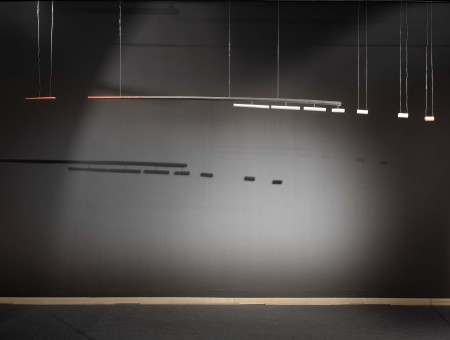

The first gallery of the Bunkier show features a reinstallation of the original Krzysztofory exhibition, comprising a group of dramatically spot-lit and modestly scaled sculptures. Flat, linear and tubular forms made of wood and cables, painted black and white with touches of red, are set low on the floor or suspended at various heights. Some bear anthropomorphic features, reminiscent of contours of faces or torsos, while others imply a kind of kineticism. Grand Spear (1962), for instance, is a long, pointed, spear-shaped piece of wood suspended horizontally in the air with a series of smaller pieces hung in succession behind it, painted in gradations of grey, white and red. The spear’s aerodynamic shape and its suspension on thin strings suggest that it is flying, and the small pieces seem to be traces of the spear’s thrust. Sculptures such as this one have been unearthed in the artist’s former studios in Warsaw and Zalesie. Some of them were in an incomplete state and have been meticulously reconstructed with the aid of original photographs and by incorporating the fragments that survived.

The artist started using photography as part of his sculptures as early as the mid-1960s. At the same time he also choreographed performative acts to be photographically documented in sequences, often taken by his friend the artist–photographer Eustachy Kossakowski. The rigorous conceptual structure of this oeuvre is counterbalanced by the frequent use of figuration and a penchant for idiosyncratic narratives. Linguistic and visual puns undermine the formal logic of Krasiński's work. In ‘Interventions’, a series of assemblages produced since the 1970s, axonometric representations of interiors seem to concede the impossibility of accurately rendering spaces on two-dimensional surfaces. In addition, a series of large, suspended rectangular mirrors create fragmented reflections of the exhibition space and its viewers, which appear now and then as fleeting portraits. These mirrors further complicate the problem of space in many of Krasiński's installations, implicating the viewer in the interplay of represented space and the space of the exhibition.

The truly revelatory coup of the show is a group of figurative works from the late 1950s that Krasiński published in Polish style and culture magazines such as Ty i Ja (You and Me) or Polska, which published international and Polish fiction writing, short prose and poems. These magazine illustrations testify to Krasiński's ongoing rapport with literature. Stylistically and thematically they belong to a local variation of the neo-Surrealist Grotesque that typified the brief so-called thaw in Communist Poland after Stalin’s death. Sundials fitted with pendulums, jazz trumpets, pistols, cat-eyed ladies and ladylike cats, crescent moons and lone figures in deserted landscapes populate these tiny masterpieces. A larger painting shows an iconic portrait of a female skeleton with some real hair styled as a wig around the skeleton’s painted mannequin head. These unusual works reveal some important sources of Krasiński's vocabulary, not only in Surrealism but also in the sombre, funereal and ascetic aspects of the Baroque and in the tradition of 19th-century Polish Romanticism that reaches far into the 20th century, with its focus on omnipresent death, unrequited love and political and emotional exile. They are snapshots from the abyss that suddenly opens wide in the midst of mundane life.