Gabrielle Goliath’s Inquiry into Loss, Memory and Mourning

At Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, the artist presents a video that addresses the issue of gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa

At Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, the artist presents a video that addresses the issue of gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa

In the early afternoon of 24 August 2019, Uyinene Mrwetyana, a 19-year-old student at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, was running an errand. She went to the post office in Clareinch to fetch a parcel. Working behind the counter was 40-year-old Luyanda Botho. Having convinced Mrwetyana there was an issue with her parcel, Botho told her to come back later in the day when, unbeknownst to her, the other staff members would have gone home. Upon Mrwetyana’s return, Botho locked the door and proceeded to rape, torture and bludgeon her to death.

On 31 August, a week after the murder – which resulted in national outrage, protests and calls for the government to intervene in the epidemic of violence against women in South Africa – two more women were found dead: Aviwe Wellem, a 21-year-old student who was raped and stabbed in her bed in the Eastern Cape village of Dutywa; and Sisanda Fani, a young mother killed in her car outside a townhouse complex. She had been shot in the head. Between 25 August 2019 and 25 August 2021, there have been 463 fatalities – including three men – in incidents of gender-based violence and femicide.

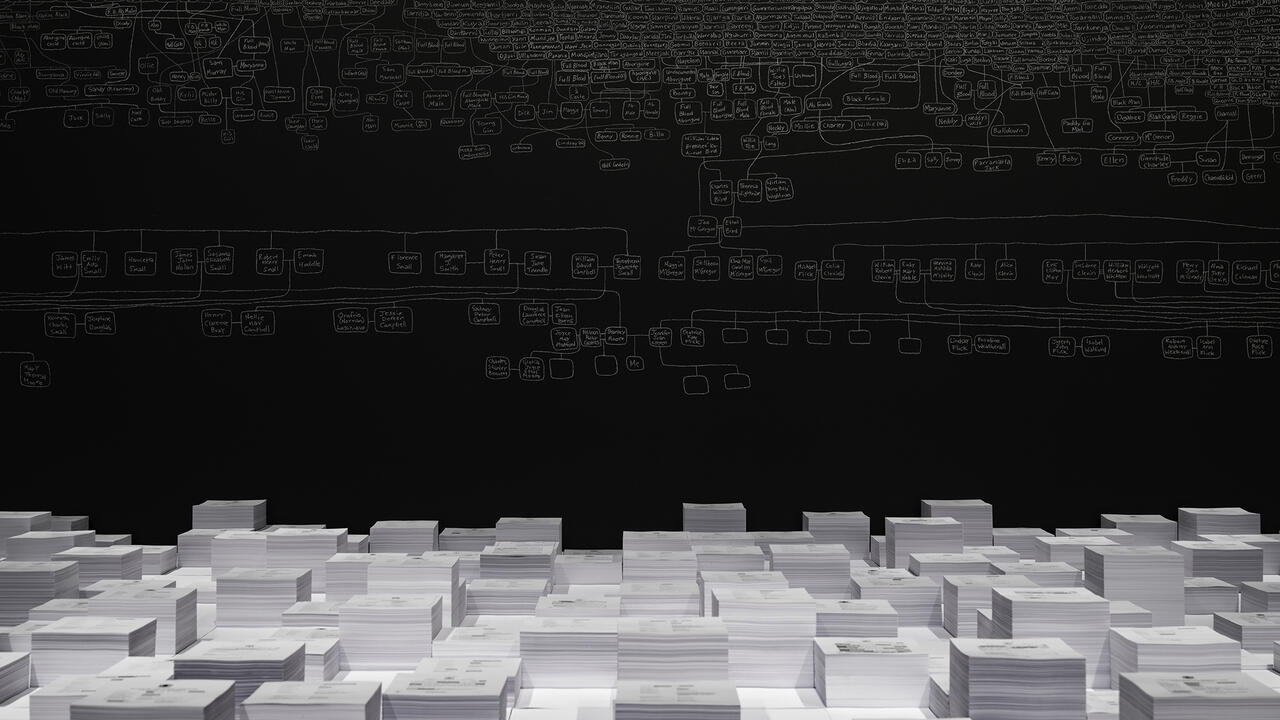

In Chorus (2021), a searing 23-minute, two-channel video and sound installation presented at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, artist Gabrielle Goliath attempts to remember and honour these women – with a focus on Mrwetyana – whose lives were violently cut short at the hands of men. And ‘attempt’ is the operative word here, for how can anyone truly represent loss and the memory of those no longer with us? Goliath herself readily admitted to me, when we spoke recently, that there is an ‘inherent limit of representing traumatic experience’. How can we portray this anguish appropriately in a way that doesn’t reproduce the violence that has already occurred? For Goliath, it lies in the voice of lament, the collective breath, the sound of mourning in ritual.

On the left-hand screen of the video installation, 46 men and women in black and grey gowns – members of the University of Cape Town choir – slowly ascend and take their places on cascading black steps. They stand in total darkness: only their bodies and the faint outline of the platform remain visible. Their expressions are solemn and sad. Some of them knew Mrwetyana. A few of them went to the same school, shared classes together. In unison, they start to hum. ‘The idea of breath and voice in unison – the transition of breath and voice from one person to a chorus, the collective – is holding one another and each other in this moment,’ Goliath explained to me.

On occasion, some of the mourners stop humming to catch their breath, while others continue, covering for their partners. At some points, the sound is guttural, discordant; at others, processional, ritualistic – the staging of a tradition. Halfway through the video, an unbearable sadness creeps in and envelopes you. There is no narrative arc here. There is no resolution. There is no break. There is only prolonged sorrow.

Chorus is a continuation of Goliath’s inquiry into loss and memory that started in 2015 with Elegy, a seven-channel video and sound installation in which individuals voice their lament over the loss of victims to gender-based violence. Four years later, Goliath produced This Song Is For … (2019), a 22-channel audio-visual work featuring evocative songs chosen by survivors of sexual assault recited by an ensemble of women and gender-queer performers. Each piece is led by a single individual, who repeatedly breaks from song into solemn humming.

In Chorus, however, there is a shift. On the one hand, Goliath moves from representations of individual mourning to the powerful act of lamenting as a group. In so doing, Goliath signals that this grief is not only for the deceased’s loved ones or South Africans to bear, but one that transcends geography. On the other, the installation’s right-hand screen features an empty dais devoid of singers – perhaps denoting the absence of the departed women. Yet, the silence on this side serves to magnify the sense of mourning and yearning for a South Africa free from the tragically normative violence that incited this work, in a country where, according to the South African Police Service, a woman is murdered every three hours.

In such circumstances, works like Chorus feel inevitable. Goliath, however, insists that the work is not to be seen in this light, telling me: ‘It’s not holding towards a future of black, brown, queer death as inevitable, but towards life, and to commemorate these losses.’ It confronts trauma without evoking violence or the feeling of suffering – even though the constant humming might, at times, make us uncomfortable. It immerses the viewer in what is at stake here: that the lament and ritual mourning of this violence is not only to be borne by those personally affected but, really, by all of us.

Gabrielle Goliath’s ‘Chorus’ is on view at Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, until 10 December.

Main image: Gabrielle Golaith, Chorus, 2021, 2-channel video & sound installation, variable dimensions. Courtesy: © Goodman Gallery Johannesburg, Cape Town and London