Gretchen Bender’s ‘Visual Worlds at the Century’s End’

Once labelled a ‘TV terrorist’, the video artist returns with her first posthumous retrospective at Red Bull Arts New York

Once labelled a ‘TV terrorist’, the video artist returns with her first posthumous retrospective at Red Bull Arts New York

In the second half of the 20th century, TV invaded the American home, reconfiguring and rewiring the social and emotional coordinates of the nuclear family. Like Hollywood director Steven Spielberg, the late multi-media artist Gretchen Bender, born in 1951, was in the first American generation to be raised on TV. While the two Baby Boomers took radically different paths in their work, both share an origin story that focused on television in their now quintessentially 1980s-work. Spielberg rose to prominence with high-tech blockbusters like E.T. and Poltergeist (which he produced) – movies in which the occult and the extra-terrestrial invade the American family (usually broken) via a television set. For Bender, labelled a ‘TV terrorist’ by one Los Angeles-based newspaper, the old CRT TV monitor is a kind of Rubik’s Cube: a hard, sculptural object that she plays with over and over, assembling and reassembling the electronic boxes into various patterns and shapes.

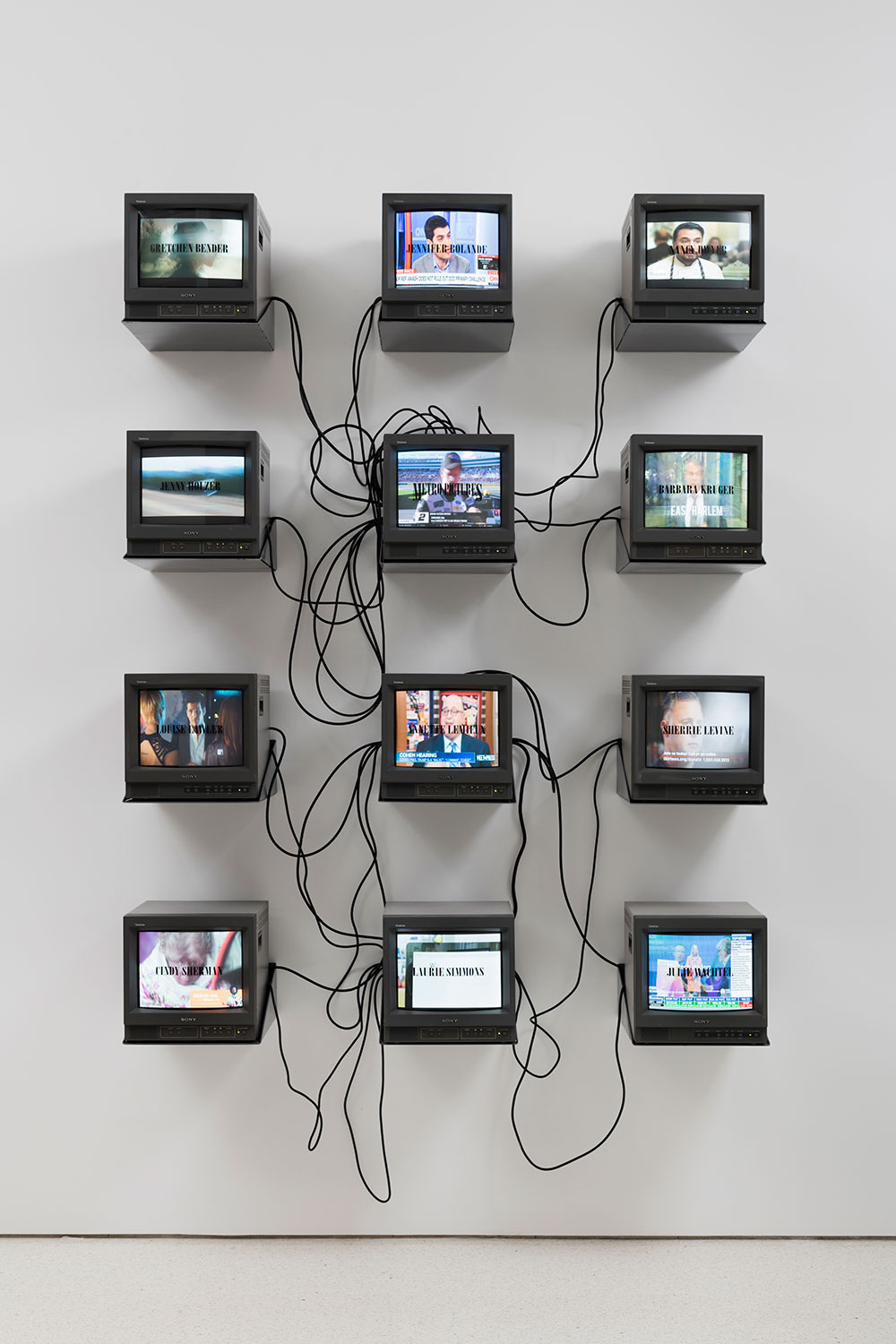

Curated by Maxwell Wolf, Bender’s first posthumous retrospective, ‘So Much Deathless’, consists of video works, silkscreens, photographs, sculptures and multi-media collaborations with artists like Stuart Argabright and Bill T. Jones. The show culminates in the astonishing tour-de-force, Total Recall (1987), an 18-min installation consisting of 24 monitors and three projection screens. In TV Text and Image (1986) and Aggressive Witness-Active Participant (1990), Bender experiments with present-day newscasts, which play on the muted screens of monitors mounted to walls like paintings. Echoing Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger’s meta-phraseologies, Bender stencilled words and axioms like, ‘Nostalgia’, ‘Dream Nation’, ‘Relax’, ‘I’m Going to Die’, ‘Class Race Gender’, ‘People with AIDS’ and the names of the 11 participating female artists across the monitors, creating her own oppositional texts and calling our attention to what she referred to, in a 1987 BOMB magazine interview with Cindy Sherman, as corporate television’s ‘equivalent flow.’

In People in Pain (1988), a 42-feet-long, heat-set vinyl cenotaph, recreated by Philip Vanderhyden for the 2014 Whitney Biennial, Bender illuminates 90 in-production movie titles – a list she culled from trade magazines like The Hollywood Reporter and Variety magazine in 1987. The warped black vinyl sculpture looks like a pool of television monitors melted into one crumbled movie screen. As in the seminal series, ‘The Pleasure is Back’ (1982), the power of roll call and nomenclature, both subliminal and exposed, is treated as theatrical exposition. Bender, like Jean-Luc Godard before her, experiments with the connotative power of typography (opening titles, intertitles, end titles), which she treats visually. Each title is at sea in its own rippled frame, as well as in a ‘cannibalistic river’ (BOMB) of representation. Bender’s titles, in People in Pain, and more generally, are cultural encryptions. They signal, forecast and lay the ground for future works. Shown both before and after the films premiered, memory here is the arbitrary commemoration of both anticipated and lost meaning, forgotten and remembered movies – the mourning of not just vinyl, or outmoded representational forms like cinema, but materiality in general.

The neon titles of People in Pain first appear at the end of Total Recall. The latter is a brilliant and elaborately coordinated televisual symphony of film fragments, corporate logos, TV promos, computer graphics, news broadcasts, movie titles and the faces of Hollywood stars. What is so interesting about Bender’s use of found footage in her video work is the physical way in which they are rendered and abstracted, resulting in something uncanny and ominous, familiar and secret. In his essay ‘Screen Memories’ (1899), Sigmund Freud writes that the screen memory is the memory that comes in to hide and express typically unconscious mental content. Bender uses found footage similarly. The movies of the 1980s, teleported via TV, certainly functioned this way. Mass media is a screen memory for our increasingly mediated lives. Lives that have become the songs we listen to, the things we buy, the celebrities we fantasize about, the sex we watch others have.

As television became a conduit for the transmission of different media from different times, movies, advertising, music, news footage, video games and pornography became virtual surrogates for lived experience. Jaws (1975), which appears as a fragment in Total Recall, was a staple in my own ‘80s childhood because of the WPIX channel, one of the television stations and logos Bender samples, along with AT&T (which she referred to as the Death Star), General Electric, RCA, CBS, Toshiba, HBO and Fox. The WPIX’s famous ‘Circle 11’ logo predated the existence of the World Trade Center buildings, which it closely resembled, and which I grew up seeing out of my window. The WPIX channel, also known as 11 WPIX Plaza, ran movies every weekend, movies that were edited for syndication; movies that I watched for the first time at home – on TV or VHS – rather than at the theatre. These movies were taken out of social and temporal context, and I rarely saw them from start to finish, resulting in a kind of hauntological time-loop.

In Total Recall, Bender shatters and decentralizes the logos of both the movie event and the single movie screen, opting instead for an ensorcelling kaleidoscope of multiple screens and channels that pulse visually and sonically – set to Stuart Argabright’s jarring, hypnotic score – highlighting the more possessive and fetishistic mode of spectatorship that arose in the 1980s with the advent of home video. In fact, Bender’s expanded cinema emerges directly out of the repeat viewings enabled by the VCR and remote control: the option to fast forward, rewind and freeze a film over and over. An affect of death, as theorist Laura Mulvey argues in Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image (2005), that delays and repeats cinema. Yet, Bender doesn’t simply shun the mesmeric power of mass media. Rather, she turns it into an audio-visual primal scene, charting the ‘making and unmaking of visual worlds at the century’s end,’ as she put it in her proposal for So Much Deathless, another expanded cinema project Bender never finished due to her death in 2004. Only the four-page proposal, exhibited in a vitrine in the gallery, remains.

Total Recall – first installed at The Kitchen in 1987 – takes its title from a line in Philip K. Dick’s 23-page short story, ‘We Can Remember It for You Wholesale’ (1966). Bender’s installation debuted eleven years after Dick’s story was published, and three years before Paul Verhoeven’s 1990 adaptation, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sharon Stone. One of the last of the non-digitally composed special effects movies, Verhoeven explains in a DVD featurette: ‘I thought it was extremely important, from a philosophical level, to make a movie that had two levels. And that you could never say: now we are in a dream or now we are in reality.’ Bender conceives of something similar, a current: ‘I quickly got caught up in the way in which TV moves,’ she told Sherman. ‘The movement, not even the sequence, but the movement that flattened content.’

In Verhoeven’s Total Recall, Schwarzenegger’s Douglas Quaid, in a state of ‘psychosis’, tells Melina (Rachel Ticotin), the lover on Mars he’s forgotten: ‘I don’t remember you. I don’t remember us. I don’t even remember me.’ Rekall Incorporated’s Dr Edgemar (Roy Brocksmith), who sells memories, tells Quaid, ‘You’ve got to want to return to reality.’ Bender’s Recall (in which a mysterious voice proclaims, ‘I sold you. You sold me’), like Dick’s and Verhoeven’s, is concerned with the hysterical interflow between the real and the virtual, conjuring questions about what is actual and what is imaginary; what is alive and what is dead; what we remember and what is remembered for us. The ways in which we, as viewers and media citizens, have to want or even fight for these things to be distinguishable.

Main Image: Gretchen Bender, People in Pain (detail), 1988 / 2014, ninety titles, silkscreen on paint and heat set vinyl, neon, transformers. Courtesy: © The Gretchen Bender Estate and Red Bull Arts New York; photograph: Lance Brewer