Rome's new museum, Italy's old politics

Oh, Rome. Such great buildings (the Pantheon – its cupola with the oculus open to the sky, its perfect proportions, the footsore tourists happy for a rest on its benches!).

And great gelato (check the dark chocolate sorbet at Gelateria dei Gracchi, Via dei Gracchi 272 and Viale Regina Margherita 212), and a contemporary art scene putting on a real show and effort on the occasion of last weekend’s opening to the public of the first Italian state museum for contemporary art and architecture, the MAXXI (the acronym stands for Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo, National Museum of 21st century Art): tonnes of shows in institutions, private foundations and galleries, plus an art fair, plus another museum, the MACRO (Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma) opening a new wing. Oh, Rome – but then, of course, the dire politics and a less than happy encounter between contemporary art and architecture.

At the press conference on the occasion of the first exhibitions opening in architect Zaha Hadid’s ambitiously torn and twisted, fair-faced concrete structure (some call it silver boa, some fettucini), the Italian Minister of Culture Sandro Bondi stated that the institution’s completion was a merit of Berlusconi. The statement prompted spontaneous boos and hisses from the mostly Italian journalists, as the right-wing government is in fact known for its hostility towards contemporary art and architecture, suspected to be strongholds of the liberal left. Bondi qualified his remark a few sentences later by saying that of course previous governments had their merits in this too. Hadid sat next to him, patiently, with a ring as big as a knuckle-duster, and a dramatic dress with a standing black collar worthy of an opera star who has seen buffos come and go. (Hadid had to deal with no less than six different Ministers of Culture during the eleven years it took to finish the 150 million Euro building which was initially planned to open in 2005.)

The day after, rumour had it that directly after the press conference Sandro Bondi, enraged by his statement having met with unanimously seeming disapproval, told the president of the museum foundation, Pio Baldi, something along the lines of ‘forget about the money!’, i.e. that the first Italian state museum for contemporary art and architecture would get little further support by the current government. A rumour that sounds believable given that this is the same Cultural Minister who two years ago unabashedly stated that for him contemporary art in general was something he didn’t understand and could see no beauty in; and who recently cancelled his visit to the Cannes Film Festival because of a Berlusconi-critical Italian film being screened there (Draquila – Italy shakes, a satirical documentary by filmmaker, actress and comedian Sabina Guzzanti on Berlusconi’s response to last year’s earthquake in Aquila ). Also, the museum new curator at large, Carlos Basualdo, appointed less than a month ago, when it comes to acquisitions to the museum’s collection, will have to deal with none other than Vittorio Sgarbi – the notorious media figure, politician, and ‘art critic’ who for a while authenticated paintings on a shopping channel, has always readily expressed his disdain for Arte Povera, and who has recently been appointed ‘personal advisor’ to the Cultural Minister in regard to state acquisition of art works, including MAXXI’s (he will also be curator of the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2011).

I wish I could report that Hadid’s building would have served to bolster the standing of contemporary art against this phalanx of hostile political figures. But walking up the huge suspended black staircases dominating the vast entrance hall, the impression is that of a corporate headquarter or designer hotel lobby, when even a huge 1985 painting of a beek-nosed red devil by Roman mystic conceptualist Gino de Dominicis (1947–98, declared antetype of Maurizio Cattelan)

suddenly becomes the decoration above the banister (that’s the crucial difference to the Guggenheim in New York, where the upward-leading spiral is seamlessly integrated into the wall and thus simultaneously a gallery); it get’s even worse with smaller works displayed in huge wall-mounted vitrines.

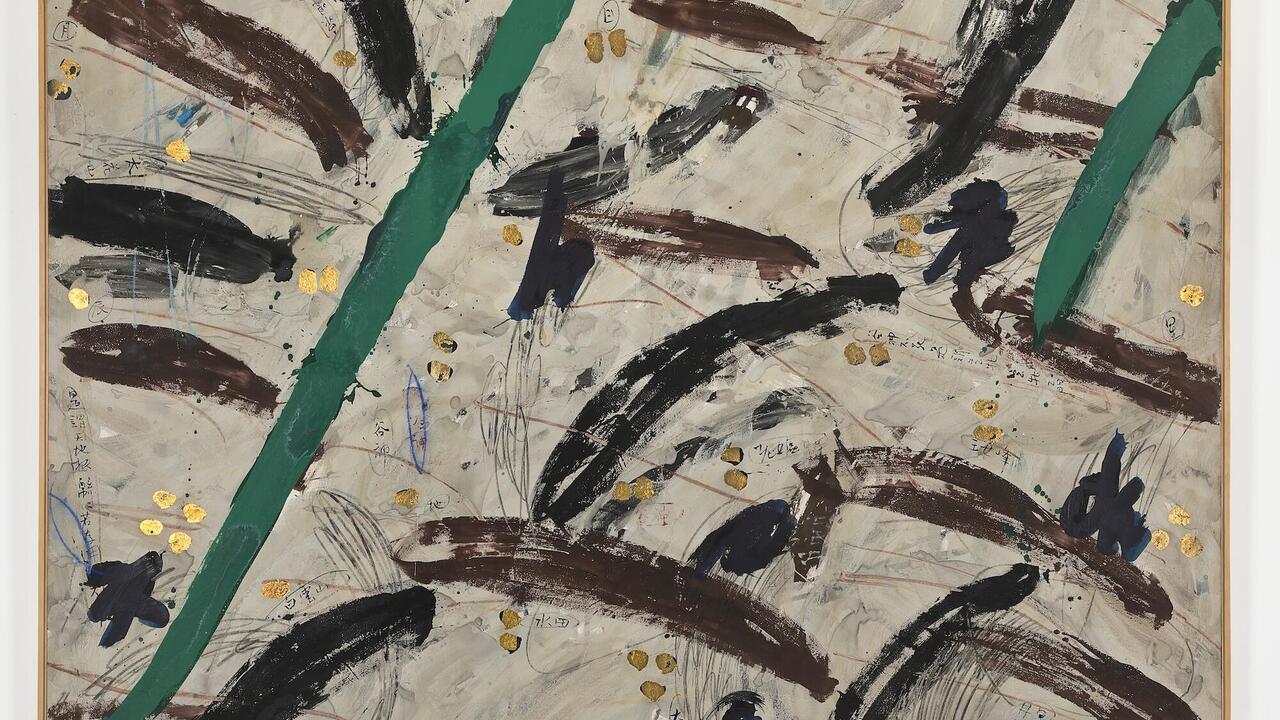

Ironically, the great early work of De Dominicis – including his seminal 1971 video Attempt to Fly, involving the elegant but hapless jump down a slope with flapping arms, or a photo documenting his attempt to cause square ripples with a stone thrown into a lake – is displayed in a conventional white cube, part of an older casern building that Hadid integrated into the front façade. Up on the tilted top floor however, the exhibition continues with De Dominicis’ hit and miss late, largely painterly work, crammed into a labyrinth of walls hastily built for the exhibition, making you feel like you’re visiting an art fair on a sinking ship.

The disadvantages of the building in regard to display are perpetuated by unfortunate curatorial decisions in the collection, which includes some 300 works by a slightly random-seeming selection of international and Italian artists of the last 40 years or so. Two large Thomas Ruff photos are positioned directly across from an elevator, and a wall work by Lawrence Weiner, combined with a huge tapestry work by William Kentridge, awkwardly sits at the end of a bended dead end hall dominated by a huge pedestrian ramp leading downstairs, into a glass-fronted corridor that finally, truly makes you feel you’re in an airport, walking towards your gate. Again, ironically, the one part that works ok is a long stretch – with works by Gerhard Richter, Tony Ousler or the Kabakovs – that is almost white cube-ish.

Over at MACRO, the municipal Museum of Contemporary Art Rome, French architect Odile Decq designed a new wing. Previously, she has been praised for her yacht designs, and unfortunately, she applied some maritime themes to this art space, tucked between existing neighbouring buildings: a huge red bulbous ship of an auditorium sits in the middle of her structure, producing a lot of junk space all around it. On the first floor there are footbridges leading around the red ship, and another footbridge leads into and along the one major exhibition hall she added to the existing ones in the old part of the museum. Looking down at three huge exhibits (a Jannis Kounellis set of sails, a Subodh Ghupta pile of steel kitchenware, and a gigantic Mario Schifano canvas) from that footbridge, I couldn’t help but be reminded of similar footbridges leading through safari park jungles, with the art works turned into wild animals. In the old part of the building, there was a set of no less than six artists’ solo shows, all by men.

I liked Jorge Peris’ strangely idiosyncratic space of on-site salt stalactite formations, and aquariums filled with plankton; and there was an interesting documentary exhibition devoted to Graziella Lonardi Buontempo, a collector and prime mover of the early 1970s Roman art scene (she co-masterminded two seminal exhibitions, “The Vitality of the Negative in Art” and “Contemporanea”).

A reminder of a bygone era where new things seemed possible even in the Eternal City of the emperors and popes. Zaha Hadid and Odile Decq are arguably the first women ever to have built noteworthy public buildings in Rome – at a time when for Berlusconi, the only way women can come to a position of power is if they are former showgirls of one of his TV channels, appointed to his Cabinet. Disregardingly both Hadid and Decq’s structures are part of a larger problem of contemporary architecture around the world: often it threatens to reduce a building’s supposed function – in this case, the display of art for visitors’ engagement and contemplation – to a mere side-aspect of its seemingly actual function to provide visible landmarks for economical urban development statements, and photo opportunities for gala events, in the vein of a boom era that is now over. The MAXXI makes this apparent in that Hadid put the biggest emphasis on the building’s lobby, and it’s bird’s eye view (in fact it seems designed for a bird’s eye view).

Given this background, the inaugural presentation of the MAXXI (and the new MACRO wing) confront the Italian contemporary art scene with a difficult burden: in the face of right-wing flack against contemporary art (and contemporary architecture) in toto, they have to embrace it, help to make it develop well despite the difficulties, like a beloved but ill-bred child. For if they don’t, the MAXXI will be the paradigm for future politicians to turn down public engagement with other institutions or developments, saying ‘see, it didn’t work with the MAXXI, why should it work in this case’.

In some way the scene is thrown back to what it is familiar with in Italy’s art centre Milan: the good things are more or less thanks to private initiative. Two private foundations, Fondazione Giuliani, and Nomas Foundation. I failed to make the fairly long trip to Nomas, which is quite a bit north of the city centre, but I have heard good things about performance projects involving Ryan Gander and Tris Vonna-Michell, and last year’s exhibition by Rossella Biscotti, for which she transplanted the abandoned, isolated larger-than-life bronze heads of fascist monuments into the modest space (_The Heads in Question_, 2009), a succinct gesture at a time when Silvio Berlusconi, only last week, compared his political decision-making to Mussolini’s. At Fondazione Giuliani, there was a group show with a sculptural emphasis, with a greatly stubborn piece blocking a doorway by Manfred Pernice, and another well-working piece by aforementioned Jorge Peris (a ceiling coming down at you once you enter the space, blocked only by a ladder standing around).

A group show entitled Things You Never Saw, comprised of works from five private collections highlighted the range of good work that resides in Italy, though the sloppy instalment between makeshift walls in an otherwise spectactular former hospital hall near St. Peters Cathedral made it hard to fully appreciate it. A piece by Jimmy Durham was impressive nevertheless: an Ikea-style office, with sofa and copier etc., covered in thrown cement (we all know the feeling). It’s from the collection of Maurizio Morra Greco (full disclosure: in 2008 I curated a show at Morra Greco’s foundation in Naples), who showed me around and explained the backgrounds of the different collectors, one of whom, Annibale Berlingieri, is a Marchese in his eighties, whose father once urged him to do something useful, so he became a collector. As one might suspect, the father wasn’t too excited about the weird art the son bought; but maybe he would have been relieved to learn that eventually one of the works, Eight Elvis by Warhol, of 1963, was sold for 100 Million Dollars last year (no big Warhol’s here, but still a nice Lucio Fontana for example).

Another highlight was the small, but concise Philip Guston show at Museo Carlo Bilotti (another collector foundation, initially private, however now under the municipality of Rome). It consisted of a cycle of works that Guston did on a hiatus at the American Academy in Rome, 1970–71, after his show of figurative work at Marlborough Gallery New York had met with abrasive derision, turning him into the official traitor of abstract expressionism. In Rome, his new language of simplified comic stumps and hoods and shoe soles collided productively with the Roman stumps of columns and former glory. One painting is a homage to his Italian painter heroes (de Chirico, Titian etc.), simply stating their name next to a white canvas on an easel, and a switched-on light bulb – a true comic style rebus with a deadpan denouement.

Another interesting show is on at the Istituto Svizzero, or Swiss Institute, co-curated by Kunsthalle Basel’s Adam Szyzmcyk and the Institute’s Salvatore Lacagnina (formerly director of Galleria Montevergini in Syracuse, Sicily). It’s inspired by Malcolm Lowry’s short story ‘Strange Comfort Afforded by the Profession’, in turn inspired by a visit to the Keats-Shelley-House in Rome (the show extends to it, as well as to a neighbouring Franciscan cloister, an antiquarian bookshop, and the Non-Catholic Cemetery of Rome, where Keats and Shelley buried). I especially liked the Duchamp-reappropriations by conceptual veteran Franco Vacari; and Ross Birrell’s and David Harding’s twin video installation of two Cubans singing Guantanamera – one by José Andres Ramirez from Guantanamo, the other by exiled by Rennes Barrios from Miami; the song’s national hero José Marti is claimed both by pro-Costra and exiled Cubans alike. Finally I want to shortly mention Nathaniel Mellor’s show at gallery Monitor, which brought his short film The Seven Ages of Britain Teaser to Rome (Mellors presented it in one room, and the animatronic rubber face starring in it, lying helplessly on the floor, in another). Produced for the BBC it features the ‘Seven Ages of Britain’ history show’s presenter David Dimbleby voicing a mask made from his own face, which is the protagonist of a strangely absurd post-Monty Python moment involving ancient gladiators and current special effects, letting dumbness collide with sophistry. Which, thinking of buffo figures like Bondi and Sgarbi, makes the work all the more appropriate to be shown in Rome these days.

PS: some more links –

Caravaggio, on until 13 June (terrible exhibition architecture, terrible wall texts, terribly crowded, but of course still worth the visit, bringing together authentic Caravaggios from around the world)

Christopher Wool at Gagosian Rome

De Chirico at the Palazzo delle Expositioni, and a new large installation in response

to De Chirico by Giulio Paolini

Turin artist duo Botto & Bruno at Galleria S.A.L.E.S.

VEDO COSE CHE NON CI SONO, curated by Sebastian Cichocki, at the Istituto Polacco, feat. work by Wojciech Bakowski, Tania Bruguera, Oskar Dawicki, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Sanja Ivekovic, Deimantas Narkevicius, Agnieszka Polska, Katerina Seda, and Piotr Uklanski

Another noteworthy group show, at Federia Schiavo Gallery

A show about Michigan 1970s band/artist collective Destroy All Monsters (which featured Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw), presented by the DEPART Foundation and Rome-based NERO Magazine at the American Academy in Rome.

Nice new small hotel where I staid – if you like a nice chat with the owner (she’s very nice and put fresh flowers in the rooms).

Great unconventional food at Pastificio San Lorenzo (thank’s Mario Codognato for pointing us there)

great conventional food at that Hosteria, corner of Via Giovanni Battista de Rossi, and Largo 21 Aprile, near the Villa Massimo (thank’s Heidi Specker for taking us there).

Oh, Rome. Such great buildings (the Pantheon – its cupola with the oculus open to the sky, its perfect proportions, the footsore tourists happy for a rest on its benches!).

And great gelato (check the dark chocolate sorbet at Gelateria dei Gracchi, Via dei Gracchi 272 and Viale Regina Margherita 212), and a contemporary art scene putting on a real show and effort on the occasion of last weekend’s opening to the public of the first Italian state museum for contemporary art and architecture, the MAXXI (the acronym stands for Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XXI Secolo, National Museum of 21st century Art): tonnes of shows in institutions, private foundations and galleries, plus an art fair, plus another museum, the MACRO (Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma) opening a new wing. Oh, Rome – but then, of course, the dire politics and a less than happy encounter between contemporary art and architecture.

At the press conference on the occasion of the first exhibitions opening in architect Zaha Hadid’s ambitiously torn and twisted, fair-faced concrete structure (some call it silver boa, some fettucini), the Italian Minister of Culture Sandro Bondi stated that the institution’s completion was a merit of Berlusconi. The statement prompted spontaneous boos and hisses from the mostly Italian journalists, as the right-wing government is in fact known for its hostility towards contemporary art and architecture, suspected to be strongholds of the liberal left. Bondi qualified his remark a few sentences later by saying that of course previous governments had their merits in this too. Hadid sat next to him, patiently, with a ring as big as a knuckle-duster, and a dramatic dress with a standing black collar worthy of an opera star who has seen buffos come and go. (Hadid had to deal with no less than six different Ministers of Culture during the eleven years it took to finish the 150 million Euro building which was initially planned to open in 2005.)

The day after, rumour had it that directly after the press conference Sandro Bondi, enraged by his statement having met with unanimously seeming disapproval, told the president of the museum foundation, Pio Baldi, something along the lines of ‘forget about the money!’, i.e. that the first Italian state museum for contemporary art and architecture would get little further support by the current government. A rumour that sounds believable given that this is the same Cultural Minister who two years ago unabashedly stated that for him contemporary art in general was something he didn’t understand and could see no beauty in; and who recently cancelled his visit to the Cannes Film Festival because of a Berlusconi-critical Italian film being screened there (Draquila – Italy shakes, a satirical documentary by filmmaker, actress and comedian Sabina Guzzanti on Berlusconi’s response to last year’s earthquake in Aquila ). Also, the museum new curator at large, Carlos Basualdo, appointed less than a month ago, when it comes to acquisitions to the museum’s collection, will have to deal with none other than Vittorio Sgarbi – the notorious media figure, politician, and ‘art critic’ who for a while authenticated paintings on a shopping channel, has always readily expressed his disdain for Arte Povera, and who has recently been appointed ‘personal advisor’ to the Cultural Minister in regard to state acquisition of art works, including MAXXI’s (he will also be curator of the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2011).

I wish I could report that Hadid’s building would have served to bolster the standing of contemporary art against this phalanx of hostile political figures. But walking up the huge suspended black staircases dominating the vast entrance hall, the impression is that of a corporate headquarter or designer hotel lobby, when even a huge 1985 painting of a beek-nosed red devil by Roman mystic conceptualist Gino de Dominicis (1947–98, declared antetype of Maurizio Cattelan)

suddenly becomes the decoration above the banister (that’s the crucial difference to the Guggenheim in New York, where the upward-leading spiral is seamlessly integrated into the wall and thus simultaneously a gallery); it get’s even worse with smaller works displayed in huge wall-mounted vitrines.

Ironically, the great early work of De Dominicis – including his seminal 1971 video Attempt to Fly, involving the elegant but hapless jump down a slope with flapping arms, or a photo documenting his attempt to cause square ripples with a stone thrown into a lake – is displayed in a conventional white cube, part of an older casern building that Hadid integrated into the front façade. Up on the tilted top floor however, the exhibition continues with De Dominicis’ hit and miss late, largely painterly work, crammed into a labyrinth of walls hastily built for the exhibition, making you feel like you’re visiting an art fair on a sinking ship.

The disadvantages of the building in regard to display are perpetuated by unfortunate curatorial decisions in the collection, which includes some 300 works by a slightly random-seeming selection of international and Italian artists of the last 40 years or so. Two large Thomas Ruff photos are positioned directly across from an elevator, and a wall work by Lawrence Weiner, combined with a huge tapestry work by William Kentridge, awkwardly sits at the end of a bended dead end hall dominated by a huge pedestrian ramp leading downstairs, into a glass-fronted corridor that finally, truly makes you feel you’re in an airport, walking towards your gate. Again, ironically, the one part that works ok is a long stretch – with works by Gerhard Richter, Tony Ousler or the Kabakovs – that is almost white cube-ish.

Over at MACRO, the municipal Museum of Contemporary Art Rome, French architect Odile Decq designed a new wing. Previously, she has been praised for her yacht designs, and unfortunately, she applied some maritime themes to this art space, tucked between existing neighbouring buildings: a huge red bulbous ship of an auditorium sits in the middle of her structure, producing a lot of junk space all around it. On the first floor there are footbridges leading around the red ship, and another footbridge leads into and along the one major exhibition hall she added to the existing ones in the old part of the museum. Looking down at three huge exhibits (a Jannis Kounellis set of sails, a Subodh Ghupta pile of steel kitchenware, and a gigantic Mario Schifano canvas) from that footbridge, I couldn’t help but be reminded of similar footbridges leading through safari park jungles, with the art works turned into wild animals. In the old part of the building, there was a set of no less than six artists’ solo shows, all by men.

I liked Jorge Peris’ strangely idiosyncratic space of on-site salt stalactite formations, and aquariums filled with plankton; and there was an interesting documentary exhibition devoted to Graziella Lonardi Buontempo, a collector and prime mover of the early 1970s Roman art scene (she co-masterminded two seminal exhibitions, “The Vitality of the Negative in Art” and “Contemporanea”).

A reminder of a bygone era where new things seemed possible even in the Eternal City of the emperors and popes. Zaha Hadid and Odile Decq are arguably the first women ever to have built noteworthy public buildings in Rome – at a time when for Berlusconi, the only way women can come to a position of power is if they are former showgirls of one of his TV channels, appointed to his Cabinet. Disregardingly both Hadid and Decq’s structures are part of a larger problem of contemporary architecture around the world: often it threatens to reduce a building’s supposed function – in this case, the display of art for visitors’ engagement and contemplation – to a mere side-aspect of its seemingly actual function to provide visible landmarks for economical urban development statements, and photo opportunities for gala events, in the vein of a boom era that is now over. The MAXXI makes this apparent in that Hadid put the biggest emphasis on the building’s lobby, and it’s bird’s eye view (in fact it seems designed for a bird’s eye view).

Given this background, the inaugural presentation of the MAXXI (and the new MACRO wing) confront the Italian contemporary art scene with a difficult burden: in the face of right-wing flack against contemporary art (and contemporary architecture) in toto, they have to embrace it, help to make it develop well despite the difficulties, like a beloved but ill-bred child. For if they don’t, the MAXXI will be the paradigm for future politicians to turn down public engagement with other institutions or developments, saying ‘see, it didn’t work with the MAXXI, why should it work in this case’.

In some way the scene is thrown back to what it is familiar with in Italy’s art centre Milan: the good things are more or less thanks to private initiative. Two private foundations, Fondazione Giuliani, and Nomas Foundation. I failed to make the fairly long trip to Nomas, which is quite a bit north of the city centre, but I have heard good things about performance projects involving Ryan Gander and Tris Vonna-Michell, and last year’s exhibition by Rossella Biscotti, for which she transplanted the abandoned, isolated larger-than-life bronze heads of fascist monuments into the modest space (_The Heads in Question_, 2009), a succinct gesture at a time when Silvio Berlusconi, only last week, compared his political decision-making to Mussolini’s. At Fondazione Giuliani, there was a group show with a sculptural emphasis, with a greatly stubborn piece blocking a doorway by Manfred Pernice, and another well-working piece by aforementioned Jorge Peris (a ceiling coming down at you once you enter the space, blocked only by a ladder standing around).

A group show entitled Things You Never Saw, comprised of works from five private collections highlighted the range of good work that resides in Italy, though the sloppy instalment between makeshift walls in an otherwise spectactular former hospital hall near St. Peters Cathedral made it hard to fully appreciate it. A piece by Jimmy Durham was impressive nevertheless: an Ikea-style office, with sofa and copier etc., covered in thrown cement (we all know the feeling). It’s from the collection of Maurizio Morra Greco (full disclosure: in 2008 I curated a show at Morra Greco’s foundation in Naples), who showed me around and explained the backgrounds of the different collectors, one of whom, Annibale Berlingieri, is a Marchese in his eighties, whose father once urged him to do something useful, so he became a collector. As one might suspect, the father wasn’t too excited about the weird art the son bought; but maybe he would have been relieved to learn that eventually one of the works, Eight Elvis by Warhol, of 1963, was sold for 100 Million Dollars last year (no big Warhol’s here, but still a nice Lucio Fontana for example).

Another highlight was the small, but concise Philip Guston show at Museo Carlo Bilotti (another collector foundation, initially private, however now under the municipality of Rome). It consisted of a cycle of works that Guston did on a hiatus at the American Academy in Rome, 1970–71, after his show of figurative work at Marlborough Gallery New York had met with abrasive derision, turning him into the official traitor of abstract expressionism. In Rome, his new language of simplified comic stumps and hoods and shoe soles collided productively with the Roman stumps of columns and former glory. One painting is a homage to his Italian painter heroes (de Chirico, Titian etc.), simply stating their name next to a white canvas on an easel, and a switched-on light bulb – a true comic style rebus with a deadpan denouement.

Another interesting show is on at the Istituto Svizzero, or Swiss Institute, co-curated by Kunsthalle Basel’s Adam Szyzmcyk and the Institute’s Salvatore Lacagnina (formerly director of Galleria Montevergini in Syracuse, Sicily). It’s inspired by Malcolm Lowry’s short story ‘Strange Comfort Afforded by the Profession’, in turn inspired by a visit to the Keats-Shelley-House in Rome (the show extends to it, as well as to a neighbouring Franciscan cloister, an antiquarian bookshop, and the Non-Catholic Cemetery of Rome, where Keats and Shelley buried). I especially liked the Duchamp-reappropriations by conceptual veteran Franco Vacari; and Ross Birrell’s and David Harding’s twin video installation of two Cubans singing Guantanamera – one by José Andres Ramirez from Guantanamo, the other by exiled by Rennes Barrios from Miami; the song’s national hero José Marti is claimed both by pro-Costra and exiled Cubans alike. Finally I want to shortly mention Nathaniel Mellor’s show at gallery Monitor, which brought his short film The Seven Ages of Britain Teaser to Rome (Mellors presented it in one room, and the animatronic rubber face starring in it, lying helplessly on the floor, in another). Produced for the BBC it features the ‘Seven Ages of Britain’ history show’s presenter David Dimbleby voicing a mask made from his own face, which is the protagonist of a strangely absurd post-Monty Python moment involving ancient gladiators and current special effects, letting dumbness collide with sophistry. Which, thinking of buffo figures like Bondi and Sgarbi, makes the work all the more appropriate to be shown in Rome these days.

PS: some more links –

Caravaggio, on until 13 June (terrible exhibition architecture, terrible wall texts, terribly crowded, but of course still worth the visit, bringing together authentic Caravaggios from around the world)

Christopher Wool at Gagosian Rome

De Chirico at the Palazzo delle Expositioni, and a new large installation in response

to De Chirico by Giulio Paolini

Turin artist duo Botto & Bruno at Galleria S.A.L.E.S.

VEDO COSE CHE NON CI SONO, curated by Sebastian Cichocki, at the Istituto Polacco, feat. work by Wojciech Bakowski, Tania Bruguera, Oskar Dawicki, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Sanja Ivekovic, Deimantas Narkevicius, Agnieszka Polska, Katerina Seda, and Piotr Uklanski

Another noteworthy group show, at Federia Schiavo Gallery

A show about Michigan 1970s band/artist collective Destroy All Monsters (which featured Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw), presented by the DEPART Foundation and Rome-based NERO Magazine at the American Academy in Rome.

Nice new small hotel where I staid – if you like a nice chat with the owner (she’s very nice and put fresh flowers in the rooms).

Great unconventional food at Pastificio San Lorenzo (thank’s Mario Codognato for pointing us there)

great conventional food at that Hosteria, corner of Via Giovanni Battista de Rossi, and Largo 21 Aprile, near the Villa Massimo (thank’s Heidi Specker for taking us there).