Electrifying Memory

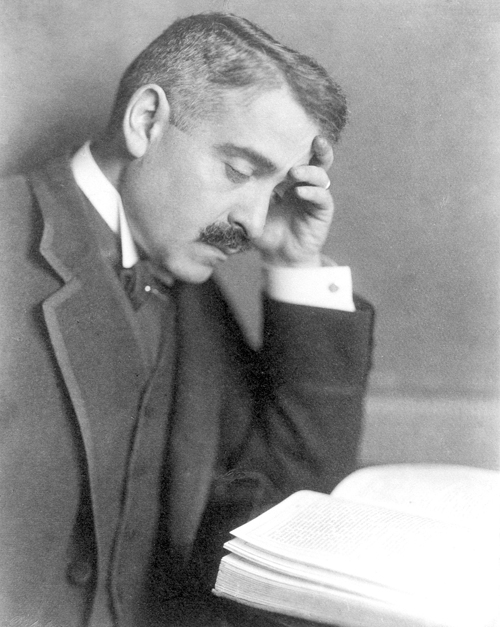

A Hamburg exhibition and a new collection of his writings shed another light on Aby Warburg

A Hamburg exhibition and a new collection of his writings shed another light on Aby Warburg

Aby Warburg didnt like listening to the radio. The ‘grand seigniorial scholar’, as Walter Benjamin called him, also disliked other technological achievements of his time. The telegram and the telephone are destroying the cosmos, Warburg claimed in a 1923 lecture about his visit to the Pueblo Indians in the southern USA in 1896. The instantaneous electric connection, he wrote, is robbing humanity of the space required for devotion and reflection, causing a relapse into the state of phobic, mythical thought.

Metaphors of electricity, which fascinated and scared him, are found throughout the work of the Hamburg art historian and cultural theorist. Seismographs who must receive and transmit waves is how Warburg describes Friedrich Nietzsche and the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, two thinkers who strongly influenced him. But Nietzsche, he adds, collapsed under the pressure of these waves, while Burckhardt may have suffered their extreme oscillations, but never fully and unreservedly said yes to them, thus preserving for himself a space of mental distance.

Today, the avenues of thought opened up by Warburg in his studies are still a regular source of inspiration not only for scholars from a wide range of disciplines, but also for artists. Suhrkamp recently published a new edition of his writings, and an exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle reconstructs Warburgs previously unknown activity as a curator.

Where European culture was concerned, his research focused primarily on the afterlife of antiquity, with a deliberate emphasis on the idea of life. For Warburgs vision of antiquity is very different to the classicist one devised by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the 18th century. For a long time, Winckelmanns praise of the noble simplicity and quiet grandeur of Greek sculptures was the yardstick by which not only the art of antiquity but also contemporary art was measured.

The legacy of antiquity on which Warburgs studies focus, on the other hand, is shaped not by peace, prudence and proportion, but, among others, by Nietzsches Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geist der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, 1872). In this work, Nietzsche contrasts the level-headed Apollonian, one-sidedly emphasized by Winckelmann, with the ecstatic Dionysian and casts antiquity as a realm fraught with tension between these two poles.

One place where Warburg discovered a set of tensions indicating the afterlife of antiquity was in the Italian Renaissance paintings of Andrea Mantegna, Antonio Pollaiuolo and Sandro Botticelli, on whom he wrote his doctoral thesis. His attention here focuses in particular on accessories of motion, including flowing garments depicted in striking formations, in which he sees expressive and emotionally charged artistic techniques that draw on sources including Greek vase painting.

Warburg also uses the term ‘engram’, coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Semon to denote a permanently inscribed mental trace in memory. The electrical energies stored and transformed within human memory across historical periods and cultures express themselves in pathos formulas, the best-known concept in Warburg’s thinking. He first used it in the lecture ‘Dürer and Italian Antiquity’ delivered in 1905 at a teachers congress in Hamburg.

This lecture centres on two important works from the prints collection at Hamburg’s Kunsthalle: Albrecht Dürer’s early drawing Der Tod des Orpheus (The Death of Orpheus, 1494) and the only known copy of a Northern Italian copperplate engraving (1470-1490) from the school of Mantegna that served Dürer as his model.

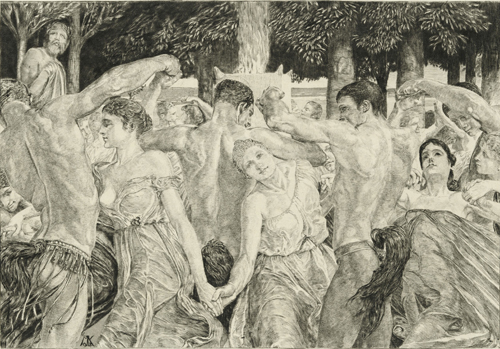

The theme of the pictures exemplifies the struggle between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. After the death of his beloved Eurydice, Orpheus renounced the love of women and used his music to honour the sun god Apollo. Dionysus, the god of ecstasy, punished Orpheus for this by sending Maenads from his entourage to beat him to death. Warburg shows that Dürers representation is a pathos formula pointing back not only to the engraving on which it is based, but also to pictures on Greek vases. Over the course of his artistic development, Dürers pendulum swung increasingly towards the Apollonian, as in his proportional studies of the Apollo of the Belvedere (BCE c.120—140). During his stay in Italy, this move towards the ideals later upheld by Winckelmann brought accusations that his works were ‘not according to ancient art’— an indication that antiquity was associated at the time more with expressiveness than with classicism.

This lecture is also included in the 900-page Suhrkamp edition Werke in einem Band (Works in a single volume, 2010) which offers extensive commentary on all texts, corrects the smoothing-over performed by previous editors and contains numerous pieces seen here for the first time. Warburg published little during his lifetime, many works having survived only as handwritten manuscripts and card indexes. A great deal has still to be looked through. The version of the lecture included in the Suhrkamp volume, for example, is not the full original manuscript, but only a version slightly supplemented in comparison to the previous abridged printings, as in the edition of Warburgs writings from 1932, edited by his colleagues Gertrud Bing and Fritz Saxl. This pioneering work has never been updated. Instead, the original texts are still often quoted from Aby Warburg. An Intellectual Biography, a lively account with a wealth of material published in 1970 by Ernst H. Gombrich (for many years director of the famous Warburg Library which was transferred from Hamburg to London in 1933).

What Gombrich, too, doesnt mention is the fact, which has until now amazingly remained unknown, that Warburg planned an exhibition to illustrate his 1905 lecture with original prints, writing to the director of Hamburgs Kunsthalle, Alfred Lichtwark, to request the loan of ten works from its prints collection. From the available sources, it is not even possible to ascertain whether or not this modest show actually took place.

Be this as it may, Marcus Hurttig has put together a reconstruction of the show at the Kunsthalle, supplemented by Renaissance prints showing how often the accessories of motion appeared. But they also feature in art made around 1905, as seen in works by Max Klinger and Otto Greiner depicting dances and festivities.

If one also looks at other pictures from the Kunsthalle collection, one finds emotional and expressive material above all in the work of the painters who joined in 1905 to form the group ‘Die Brücke’ (The Bridge). Warburgs lecture, then, coincided with the birth of German Expressionism, which painted pathos formulas into pictorial spaces that appeared to be traversed by electrical pulses. It is even claimed that Warburg was the first to use the term Expressionists in 1910. The links between his ideas and contemporary art, on the other hand, consist less in direct engagement than in intentional parallels. Mention has often been made of the similarity between Warburgs ‘Mnemosyne’ atlas (begun 1923, left unfinished on his death in 1929) and collage techniques developed at the same time. Today, for example, Danish artist Henrik Olesen applies the approach used for the atlas in his rereading of art history, into which he collages the history of the persecution of homosexuals. As in Warburgs case, this allows him to expose the fears crystallized in pictures. Might collage be the form of instantaneous connection that reopens the mental space short-circuited by electricity?

Translated by Nicholas Grindell