The Further Adventures of Parlando, Melisma and the Cookie Monster

A brief history of unique singing techniques

A brief history of unique singing techniques

A female voice rises and falls, a siren song of deep sighs and guttural moans punctuated by glottal clicks and exhaled split tones: a wave of sound that never pauses for breath. It’s unnerving, like being underwater without knowing when you’ll surface. Joan La Barbara’s seven-minute Circular Song (1974–5) employs the breathing technique of trumpet players. It rides on what she refers to as the ‘crack’ of the voice: that catch and crackle in the throat which is sometimes experienced on waking from fitful sleep. A pioneering work of Extended Vocal Technique (EVT), Circular Song appears on La Barbara’s seminal Voice is the Original Instrument (1976), a record that also includes multi-phonic singing (the simultaneous sounding of two or more pitches), circular breathing, ululation, ‘vocal fry’ and the glottal clicks that have become her signature sounds.

La Barbara’s unique vocals connect many histories. While touring Europe in the 1960s with composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich and performing predominantly in galleries – in those early days, Glass and Reich’s ‘un-musical-music’ found favour in art spaces rather than the concert hall – La Barbara encountered the work of Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman and Dennis Oppenheim. Reneging on her claustrophobic early training as an opera singer, she looked instead to adopt the mechanics of process-based art and minimal composition in order to develop the voice as a solo and multi-faceted instrument. It was a synthesis of effects that drew upon the natural sounds of popular soprano Cathy Berberian (gasping, coughing, laughing), the scat singing of Ella Fitzgerald, Mel Tormé’s ‘Velvet Fog’ voice and the teachings of her mentor and collaborator John Cage. Her virtuosic understanding of the voice saw her premiere a number of landmark compositions that included vocal parts written for her, such as Reich’s Drumming (1970), Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach (1976), and the title role in Robert Ashley’s tetralogy Now Eleanor’s Idea (1985–94).

Synthesis – of sound, image and movement – has also been key for pioneer vocalist and composer Meredith Monk, who, for many years, has used the voice as glossolalic material, an expressive form bubbling up from within that connects ancient and modern oral folk culture. Hailing from New York, Monk’s Vocal Ensemble was formed in 1978 and produced a series of groundbreaking choral works that connect her signature abstract singing language with bodily movement. In Dolmen Music (1980–81), six singers respond to the bowing of the cello; as the arm moves across strings so the breath rises and falls, creating a mesmeric call and response between performers. In Turtle Dreams (1983), minimal vocal phrasing moves from piercing siren call to child-like syncopated moan: Monk’s sound is one of playful engagement with the rhythmic structure of the voice, exploring how, as a material, it connects performers to each other and also to the audience or, as she calls it, ‘the congregation’.

Extended Vocal Technique – also known as Extra Normal Vocals – is the study and categorization of unique singing techniques. In short: odd mouth sounds. As I write, my four-month-old son is serenading me with a series of outlandish fluting squeals and low raspy sounds. These strange bubbling social noises are his first attempts to be understood. They are also temporary. Soon, rules will be learned and the particularities of vocal range and language fixed. Described by British composer Trevor Wishart as the ‘struggle to retain what was’, EVT looks to reclaim and extend the sonic peculiarities of the voice.

The voice has a material form: air molecules that, when vibrated in the throat, act on the ear. If the voice can be thought of as the original instrument then it follows that it is also the first material we play with. Can we think of the voice as a material like clay, paint or steel? It can certainly be stretched and pulled, modulated over time as timbres shift and accents are gained or lost. We believe in the voice as inalienable, unique like a fingerprint. Take, for example, a telephone conversation: the question ‘Who’s speaking?’ and the reply ‘It’s me’ insist upon the sovereignty of the individual’s voice. Yet, as we move from analogue to digital communication technologies, the voice is fractured and made alien to its source. Internet telephony – digital utilities like Skype and Google Hangouts – have a higher fidelity than older analogue systems, yet they also produce a thinner and more flexible version of the voice. We are made increasingly aware of its elasticity as we hear a loved one’s words taking on flat metallic tones due to a bad Internet connection. As the software falters, the voice drifts in and out, becoming phantom-like: haunted by the media that produces it.

There is no definitive list of EVT, nor, for that matter, much in the way of literature on the subject. Rather, it’s a stand-in term that’s used to track changes in vocal normalcy. It differs from place to place, and is culturally subjective. What is considered desirable for one part of the world – in traditional Korean pansori performance, for example, singers purposefully develop grooves and nodules on the vocal chords – can be a sign of bad health in another. Despite its appealing refusal to be fixed, there are muddied trails that suggest a past and possible future for EVT.

Between Song and Speech

Sprechstimme is a vocal style that combines elements of both song and speech. Imagine speaking the words of a song – the lyrics or libretto – but following the rhythm and pitch of musical notation. You can hear it in Bob Dylan’s unusual diction, Mark E. Smith’s laconic drawl or Rex Harrison’s pedagogic warble in My Fair Lady (1964). The first acknowledged instance of Sprechstimme – and, significantly, EVT – is in the composer Arnold Schoenberg’s 21-part melodrama Pierrot Lunaire (1912). What set it apart from earlier melodrama was the preciseness of the Sprechstimme notation, and the lack of improvisation on the singer’s part; speech that was no longer solely dramatic but instead part of the music.

Metalize, Liquify, Vegetalize, Petrify…

Extended vocals are not solely the preserve of singers and composers. James Joyce’s attention to the breakdown of language, and his application of nonsense syllables, would inspire composer Luciano Berio’s first vocal work, Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958), performed by Berberian. Writing in 1916, Futurist Filippo Marinetti called for superior forms of vocalizing that would ‘metalize, liquify, vegetalize, petrify and electrify his voice, grounding it in the matter of vibrations itself’. The Dadaist Hugo Ball constructed sound poems from syllables and individual letters, whilst Kurt Schwitters opened his Ursonate (1922–32) with the line ‘Fumms bö wö tää zää Uu, pögiff, kwii Ee.’

The Screamers

Long before punk and heavy metal used harsh vocals, screaming could be found in forms as diverse as the blues and experimental rock. In the 1950s, prior to the widespread use of amplification, the screams of blues man Howlin’ Wolf were legendary. The result of a practical need to be heard over the music and crowds in the dancehall, they also became vital to the rhythm and declamatory power of his songs. Meanwhile, Berio’s score for Sequenza III for Female Voice (1965) includes ‘emotional markings’ and suggestions for the singer’s temperament, gesture and expression that result in some unholy squeals and roars. The heady meeting of rock and roll with the avant-garde found full vent in another of New York’s female vocal pioneers. Mixing the teachings of primal scream therapy with hetai, a Japanese vocal technique from kabuki theatre, Yoko Ono revolutionized rock vocalizing with her ‘shout from the heart’ on her debut solo album Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band (1970). At the end of the track ‘Why’, you can hear John Lennon gleefully shout to the engineer, who is obviously reeling from the experience, ‘Did you get that?!’

[Missing Image]

The Prosthetic and Assisted Voice

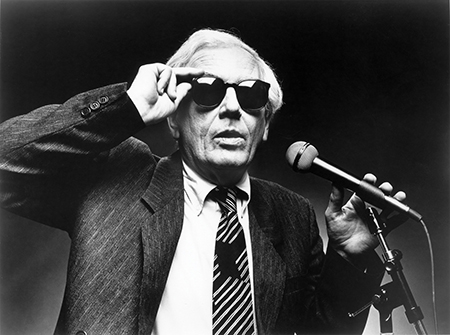

In a career spanning half a century, the ear of us composer Robert Ashley has been tuned to the rise and fall of speech and the subtleties of vocal effect that amplification allows. Ashley’s The Wolfman was first presented at Charlotte Moorman’s ‘New York Avant Garde Festival’ at Judson Hall in 1964. Described as an amplified improvisation of vocal sound, it consists of four components – minute variations of the mouth, tongue, lips and breath – to be played alongside the accompanying Wolfman Tape, a droning layer of ‘found’ sounds from the radio and past Ashley recordings. Dressed in the suit and shades of the then-popular lounge-singer, the performer, in the glare of the spotlight, leans in to the microphone and softly exhales. The result, when amplified at a high volume, is a wall of extreme and often room-clearing sound. Due to the intense volume of the piece, the vocal part has often wrongly been thought of as a scream; rather, it is a voice constrained, on the edge of audibility. With the aid of technology, it becomes a monstrous instrument.

Vocoded

Half a century after Marinetti’s call to metalize the voice, his wishes were answered by the vocoder. Short for ‘voice encoder’, the vocoder is an analysis/synthesis system used to reproduce human speech in bright electronic tones. In 1969, children’s music producer Bruce Haack released The Electric Lucifer. The album mixed the heavy sounds of psychedelic rock with Haack’s homegrown electronics, including ‘Farad’ – a prototype vocoder named after physicist Michael Faraday – which was used to process the lyrics and words of Haack’s friend and business partner Chris Kachulis. Two years later, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) would make use of the vocoder in the sung chorus and music of Wendy Carlos’s abridged version of the fourth movement of ‘Ludwig Van’s’ Ninth Symphony (1824) for the film’s soundtrack. Special mention needs to be given to a work that straddled the gap between performance art and mainstream pop: Laurie Anderson’s ‘O Superman’, which hit number two in the British singles charts in 1981. Part of her epic performance work United States (1983), ‘O Superman’ used Sprechstimme and vocoded voice, prefiguring the flattened emotional and melancholic register of what has today become commonplace for pop singers such as Imogen Heap, in her vocoded 2005 hit Hide and Seek. The Cookie Monster Death Growl

From an early age, Nicholas Bullen – founder member of the British ‘grindcore’ band Napalm Death – was drawn to the ring-modulated and processed voices of fantastic fiction, from Doctor Who (1963–ongoing) to the Britsh sci-fi series The Tomorrow’s People (1973–9) alongside novelty children’s records such as Big Bopper’s Purple People Eater Meets the Witchdoctor (1958). For Bullen, a committed C-60 demo-tape trader, the radical vocal sounds of hardcore punk arrived courtesy of the Royal Mail: from bands such as Disharge and Asylum in Britain, America’s United Mutation and Negative FX, Scandinavia’s Rattus and Japan’s GISM. He would experiment with the record deck, slowing down his Bauhaus LPS to 16rpm rather than 45rpm, which lead to a fascination with vocal re-pitching. The vocal style heard on Napalm Death’s first record, Scum (1987), is expressed in short guttural bursts, a roar of aggressive sound and gnomic political sloganeering that connects the social and political philosophy of anarchism with DIY punk ideology. It introduced a vocal technique variously referred to as the ‘death growl’, ‘unclean vocals’ and ‘Cookie Monster vocals’, after Sesame Street’s sugar-addicted, growling blue puppet.

Melisma and Auto-Tune

In 1992, Whitney Houston’s cover of the Dolly Parton song ‘I Will Always Love You’ (1973) spent 14 weeks at the top of the us Billboard charts. Significantly, it foregrounds another key form of EVT: melisma, or the singing of a single syllable while moving between several different notes. With roots in Gregorian chant and Indian ragas, it filtered into modern Western music through gospel and soul. Traditional melisma has been surpassed by technology with the advent of the pitch correcting software Auto-Tune, which synthesizes the vocal fluidity of the soul voice, bending sharp or flat notes to a pre-determined scale. Its founding pop moment was Cher’s 1998 song ‘Believe’ and, by 2005, rapper T-Pain had lathered pitch-bending like syrup across every syllable, using Auto-Tune as instrument for his album Rappa Ternt Sanga.

Human Beat-Box & Donald Duck Talk

EVT has its funny side. Combine the character of Larvell Jones from Police Academy (1984) – played by Michael Winslow, ‘the man of 10,000 sound effects’ – with the surreal mindscapes of Andy Kaufman and early Robin Williams, and you have something that approaches stand-up comedian Reggie Watts. A former musician and hiphop artist from Seattle, Watts isn’t a regular punch-line comedian. Like Kaufman, he plays a legion of characters, moving at dizzying speed between gangsta rapper, soulful crooner and British professor. Watts works with a number of key EVT techniques. He uses human beat-box, producing vocal percussive beats from old-school hiphop to a spoof of us dubstep producer Skrillex. ‘Buccal speech’, also known as ‘Donald Duck Talk’, can also be heard; it’s the sound you make by trapping and expelling air bubbles between the upper jaw and the cheek. On the recording Why Shit So Crazy? (2010), Watts recounts the (fictional) last words comedian George Carlin said to him; what follows is a stream of extended vocals from ‘buccal speech’ through to ‘vocal fry’. A lowering of the voice and loose closure of the glottis to produce croaky overtones, ‘vocal fry’ originated in the San Fernando Valley, California, with teenage girls, coupled with a pattern of speech in which every sentence ends with a question (sometimes referred to as the ‘moronic interrogative’). As a study by scientists at Long Island University in Brookville, New York, recently argued, the ‘vocal fry’ register has now become a widespread speech pattern found amongst college-age women in the US.

[Missing Image]

Demons, Aliens, Angels, Zombies

Perhaps the most beguiling instance of EVT in cinema is that of Mercedes McCambridge in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). McCambridge provided the dubbed voice of the demonically possessed child, Regan, played by Linda Blair. It was a voice that rasped, snarled and growled its way into being. In order to achieve the voice, McCambridge used sleep deprivation, cigarettes, egg yolks and liquor. Friedkin explains: ‘It was really something else. She’d just sit there in that chair looking at the screen and go, “Aaaaaaaarghh”, and you would hear these things multiplied in her throat; these strange counterpoint noises; little skittering whistles and strange creaking rattles.’ In order to preserve the mystery of Blair’s possession, onscreen early releases of the film appeared without McCambridge’s credit. It was later added following a court case in which the actress stated: ‘All of the devilish vocality is mine, all of it!’ In Alien Resurrection (1997), Sigourney Weaver’s character Ripley is cloned, and her DNA intertwined with the Alien Queen, resulting in a half-human, half-alien child. The newborn’s first and last moments – before being memorably sucked out into space – were voiced by La Barbara, with a terrifying mixture of alien sounds and primal human utterance; a decade earlier La Barbara had provided the angelic voice for Emmannuelle Béart in the American fantasy comedy Date With an Angel (1987). Mike Patton is amongst the latest vocalists to employ EVT, bringing the experimental voice work of his band Fantômas to his voice-over for the walking dead in Will Smith’s post-apocalyptic science-fiction film I Am Legend (2007).

The Topological Twist and Slight Return

From our first playful sounds through to the walking undead, the voice is central to our understanding of self and continues to be a draw for artists and musicians alike. In contemporary art, this is not simply to do with the social connotations of the voice, but also the possibilities of it as a material form, aided by new forms of production and distribution. For British artist Mark Leckey, use of extended technique – from a cappella and the digitally processed voice to DJ Screw’s ‘chopped and screwed’ vocal slowdowns – connects his work to the pop traditions of street and working-class culture, R&B and black electronic dance music. Florian Hecker’s hybrid sound/text trilogy – Chimerization, Hinge and forthcoming CD: A Script for Synthesis (2012–13) – features performers including La Barbara and Joan Jonas, working with an experimental libretto written by Iranian philosopher Reza Negarestani. Presented in three languages – English, German, and Farsi – it connects with Dada’s persistent use of multiple spoken languages. Rather than define Hecker’s process as a form of vocal extension, a closer description would be a ‘topological twist’, with sound and voice digitally melded together. A more direct relation to evt is to be found in Tino Sehgal’s recent untitled work for ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’ at the 55th Venice Biennale. A small group of performers were gathered together on the floor. One of these performers broke into a rudimentary form of human beat box – part Schwitters Ursonata, part beat-boxer Doug E. Fresh – and conjured the words to Heap’s melancholic ‘Hide and Seek’; ‘Mm, what’d you say? What you say?’, connecting the vocoded voice back to the human larynx.

A new generation of female artists and vocalists, largely from Norway, continue to explore the voice in experimental pop, from Jenny Hval to the sound sculpting of Maja S.K. Ratkje and Stine Motland. In Natural Enough (2011), Tori Wrånes sings while being hung from a tree by a braid in her hair. In New York there are examples of new vocalizing, including Jace Clayton’s stock-market-linked algorithmic work Gbadu and the Moirai Index (2013) and C. Spencer Yeh’s split-screen video installation Infinite Modular Vocal Interaction System (Eliza Study No.3) (2010) demonstrating his wide repertoire of vocal technique. EVT is a century-old form that recognizes no boundary. The ear, unlike the eye, cannot be shuttered; it takes in all sound without prejudice.