Thomas Zipp

Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK

Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK

White Dada (2008) was composed of two areas: a replica lecture theatre and a period-style gallery filled with Dada-esque works. Where the former space was large, high-ceilinged and bright, the latter was small, dark and low. Zipp’s aesthetic was immediately recognizable in both. Muted colours, fluorescent ‘chandeliers’, faces with silver tacks for eyes, a portrait of Martin Luther: all were familiar from recent installations. At the same time Zipp summoned the frisson of historical authenticity. To enter the windowless smaller space, with its benches and hessian-covered plinths, was to remember that the talismanic sites of avant-garde activity were often the back rooms of dingy cafés.

Zipp alludes to a range of conceptual systems. In the smaller room medical images were prominent: wards, nurses, surgery and a page from a textbook detailing procedures for dealing with mental illness, including electric shock treatment and ‘narcotherapy’. This latter term then connected with the drug references of the dried poppies and teaspoons nearby. The effect was to suggest a continuum between state control and transgressive behaviour, one implication being that these practices are linked rather than antithetical. Such assertions of complicity between elements normally seen as opposed are common in Zipp’s work. In its overt evocation of the avant-garde, however, ‘White Dada’ made explicit the artist’s concern with the relationship between radical art and other social and political forces. It was in the conjugation of the show’s two spaces that this relationship was most succinctly examined.

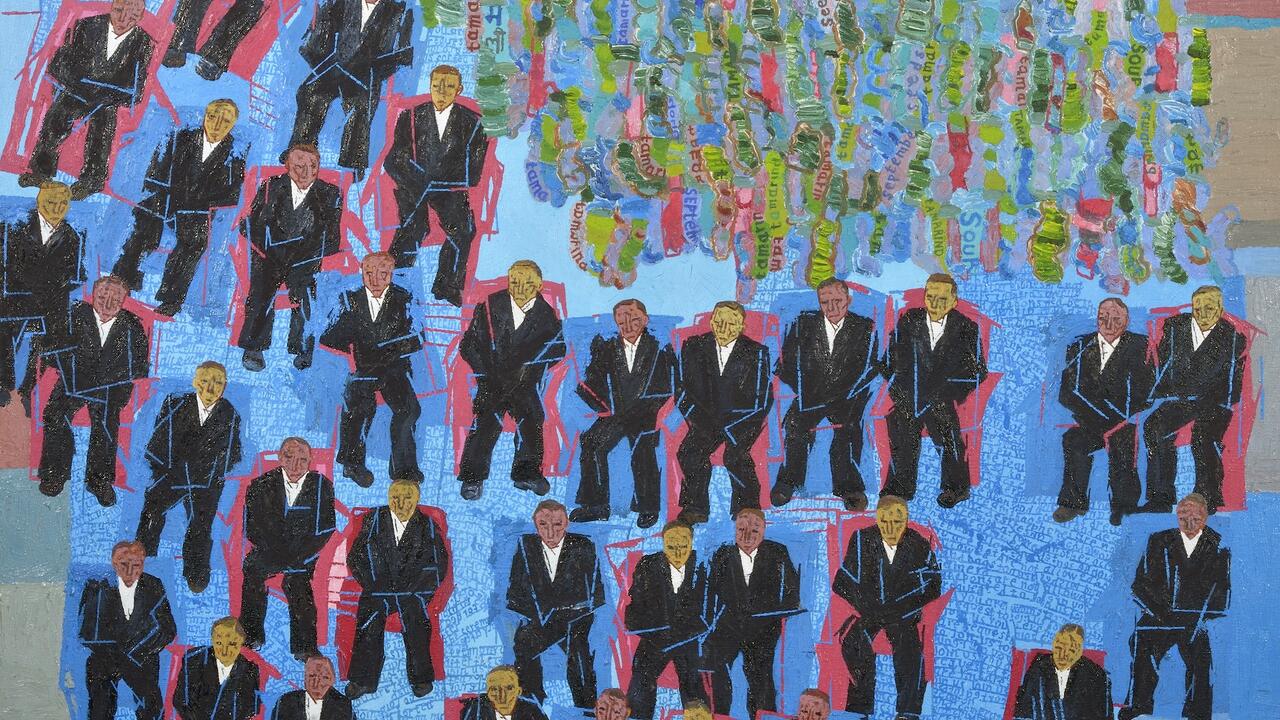

The lecture theatre’s wood panelling and tiers of uncomfortable seats suggested some 19th-century Mitteleuropean institution. Rather than the recalcitrance of the Cabaret Voltaire, the mood was one of aspiration to power and the intellectual mainstream. Botanical paintings were regularly spaced on the walls, interspersed with a repeated manifesto attacking bourgeois values and exhorting violence and ecstacy in time-honoured style. An imposing light-coloured, semi-abstract figure stood to the right, the abstract Hans Arp of its head balanced on a Jacob Epstein torso. Hanging above it was a Constructivist diagram of fluorescent tubes. The connotations were of a confident Utopian Modernism: it was year zero in the circular hall, and the large sculpture a template for the new man.

If Zipp was careful to distinguish between two forms of the avant-garde, he did not assert a banal opposition between an emancipatory Dadaism and its rivals: this would have contradicted the idea of complicity explored in the smaller room. Hence the disciplined atmosphere of the lecture hall was in turn complicated by the tokens of adolescent rebellion that occupied its centre: drum kit, organ, distortion pedals, a microphone and amp. Zipp and his band DA (Dickarsch, or ‘fat ass’) showcased their improvised rock on the opening night with a torrent of screaming that Hugo Ball might well have approved of. As a result the austere theatre and the shabby back room could not be seen as independent. Rather, the latter – with its benches along the walls, where the band waited – was a kind of antechamber for the former. In this way Zipp implicated each historical (and political) space in the other while reaching forward to touch us in the present.

The amp emitted a powerful hum, letting us know it was live and so inviting the viewer to take up the instruments and perform. By doing so we may perhaps have maintained some kind of fidelity to the event that took place here, traces of which could still be seen: the carpet stained with ash and alcohol, the wooden tiers covered in dusty footprints. And yet this was at odds with the melancholy that the empty lecture hall exuded. We were too late: the players had left the stage and the audience for anything we might do ourselves had already departed. Such ambivalence extended to the status of the band’s performance. By connecting with them through performing ourselves, could we really channel the distant creative event of Modernism? Or was the gig, like its surroundings, simply a facsimile, history repeated as farce?

The excesses of DA’s performance may have suggested the latter, seeming merely to assert tired ideas of art as transgression. Yet Zipp’s conception of Modernism as constituted though a contradiction between creativity and control demands a more complex analysis. The performance stands or falls on the question of whether it is grasped under the mannerist sign of irony or as part of a larger exploration of the contradictions at the heart of both Modernism and the last hundred years of German art and society. Zipp’s ability to pose this formal question suggests that his work does indeed afford a useful purchase on the receding event of Modernism, even as it dramatizes the problems and tensions endemic to it.