Why Was New York So Afraid of Allan Sekula?

Shamefully, the artist was not awarded a solo show in the art-world capital until six years after his death

Shamefully, the artist was not awarded a solo show in the art-world capital until six years after his death

Down the hall from artworks about labour conditions at the US–Mexico border, a slide projection shows police launching tear-gas cannisters at an unarmed multitude. In some images, curtains of chemicals close around their targets; in others, bleary-eyed casualties cope with the aftermath.

Yet the exhibition in question is not a journalistic expo of Donald Trump-era atrocities. Nor is it the 2019 Whitney Biennial, which was dubbed ‘The Tear Gas Biennial’ due to the controversy surrounding Whitney Board of Trustees vice chair and chemical-weapons magnate Warren B. Kanders, who was finally ousted last week following eight months of protests. Rather, this show is ‘Allan Sekula: Labor’s Persistence’ and, despite its contemporary relevance, the slide installation Waiting for Tear Gas [white globe to black] (1999–2000) dates, in fact, to the 1999 anti-globalization demonstrations in Seattle against the World Trade Organization, two long decades ago, which set a brutal new standard for police violence in the face of peaceful protest.

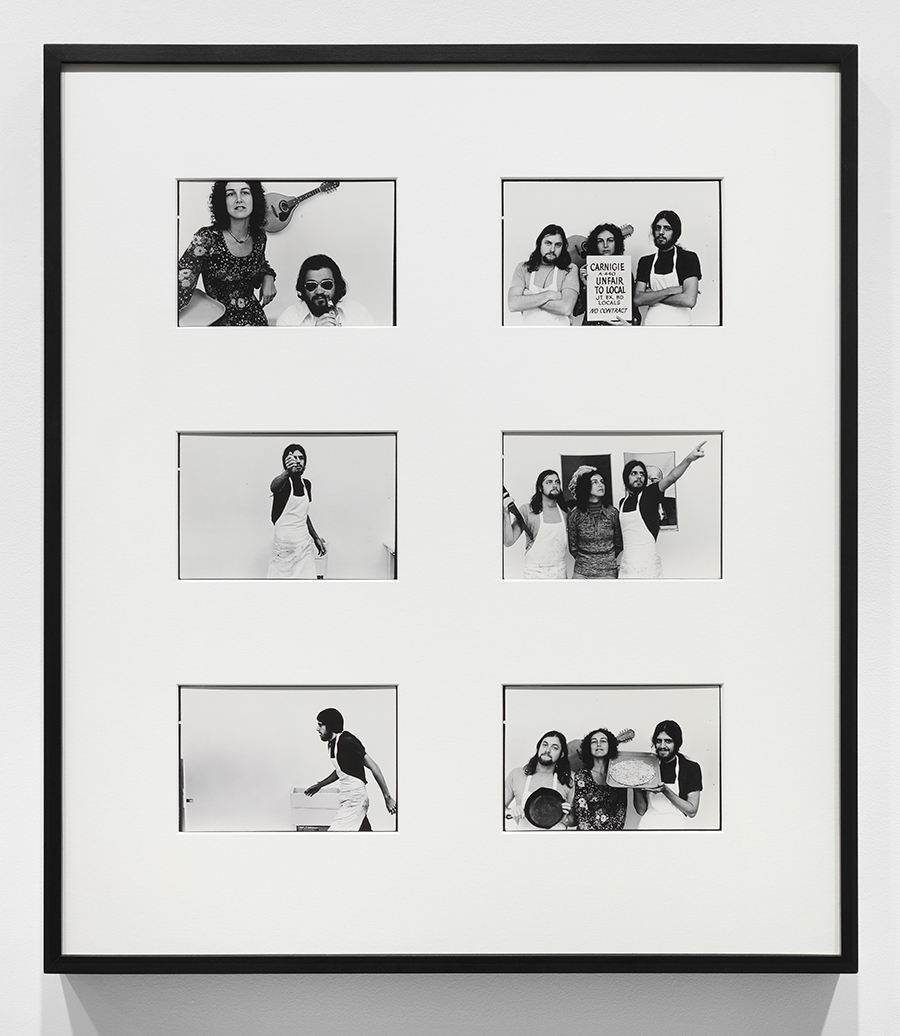

Over a 40-year career, Sekula – a theorist, historian, photographer and artist – sustained a commitment to conceptualist documentary with a critical-realist orientation, highlights of which are showcased in this mini-retrospective, an abridged version of the Spring show at the gallery’s more capacious London location. The labouring body under conditions of globalized capitalism is the artist’s perennial subject. A local/global dialectic is evident already in the early work This Ain’t China: A Photonovel (1974) – a parafiction about a failed unionization effort in a pizza shop – and becomes more salient as he turned his camera first to the shipping ports near his Southern California home, then to the international trade that binds those ports to the world. His practice increasingly adopted a maritime theme, specifically through the visual idiom of the container ship, which today accounts for about 90 percent of non-bulk cargo. Works like Freeway to China (1998–99), TITANIC’s wake (1998/2000) and the career-defining Fish Story (1989–95) develop a critique of container-capitalism through careful ensembles of images and texts in formats from books to installations. In the present exhibition, however, many works appear only in the form of token images, which limits the contextual rigour and conceptual play of more complete presentations. Another regrettable elision is the absence of film in the show. Sekula may have stubbornly resisted the moving image until late in his career, but films like The Lottery of the Sea (2006) and The Forgotten Space (2010) have become indispensable in even the most synoptic accounts of his oeuvre.

These curatorial decisions are all the more consequential given that this is Sekula’s debut solo show at a New York gallery. To be clear: Allan Sekula – contemporary of Martha Rosler, favourite of Benjamin Buchloh, author of the landmark text ‘The Body and the Archive’ (1986) – was not awarded a monographic gallery exhibition in New York until six years after his death at the age of 62. Such an oversight should seize this art-world capital with a shudder of collective shame (as if such things were possible). His exclusion reveals a rare point of unanimity in an otherwise polyvocal art scene. But why was New York so afraid of Sekula?

Possible answers spring to mind: the work can look banal at first; it requires substantial temporal and intellectual investment from its audience; both its political and aesthetic commitments fell out of fashion during Sekula’s lifetime; its unmistakable Marxism repelled art’s principal financiers (namely corporations and the super-rich) while refusing all customary aesthetic consolations. An image from Waiting for Tear Gas offers yet further insight, however. In one slide, a woman holds up a small black sphere to the camera. Another slide decodes the marble-sized enigma through its discarded shell: a 20-centimetre black cylinder that delivers 42 rubber ball rounds called ‘Stingers’ – a ‘less-than-lethal’ form of ammunition to control crowds by ‘pain compliance’. Plainly legible, the name ‘Stinger’ is a trademark of the manufacturer, Defense Technology, a subsidiary of Safariland, the very company owned by Kanders. There, 20 years ago, was an artwork warning of realities that New York art institutions preferred not to see. As the ban on this artist begins finally to be lifted, we might reasonably wonder how different the intervening decades might have been had we lived in an art world that excluded Kanders and exalted Sekula, and not, as it happened, the other way around.

‘Allan Sekula: Labor’s Persistence’ continues at Marian Goodman Gallery through 23 August 2019.

Main image: Allan Sekula, Cannery, Sanzal from ‘Dead Letter Office’, 1996–1997, triptych of Cibachrome prints, 50.5 × 198.8 × 6.3 cm. Courtesy: Allan Sekula Studio and Marian Goodman Gallery