Work in Progress: Africanus Okokon

In new hybrid paintings that will be shown at Frieze Los Angeles, the artist conjures an image of forgetting

In new hybrid paintings that will be shown at Frieze Los Angeles, the artist conjures an image of forgetting

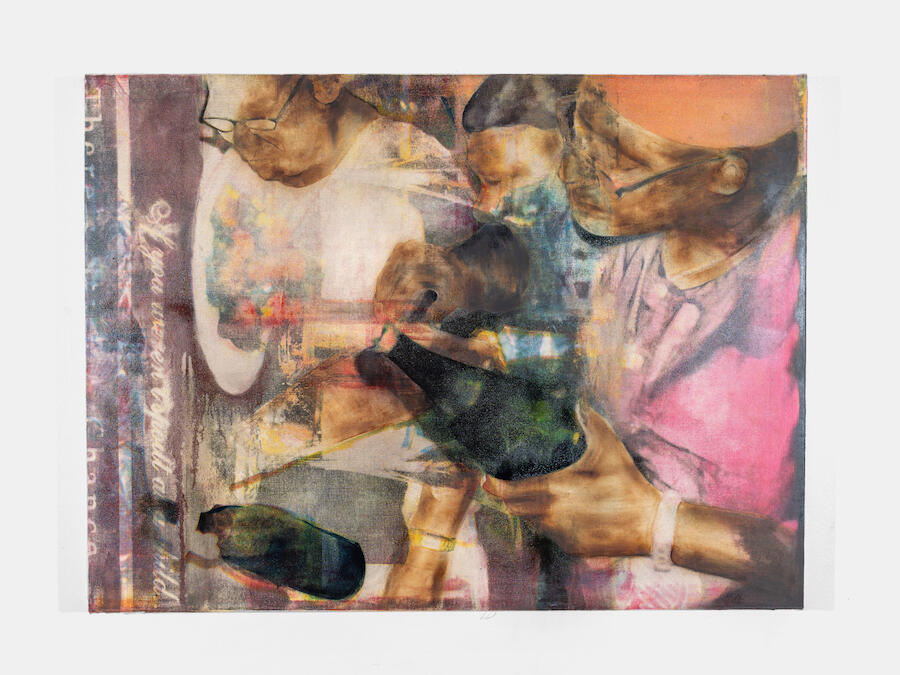

Africanus Okokon describes himself as ‘a painter who rarely picks up a paintbrush and a filmmaker who rarely picks up a camera.’ His latest paintings stem from family photo albums from Ghana and printed advertisements. Figures recede and emerge through layers of silkscreen, ink and burned coconut milk. Across painting, moving image and sound, Okokon explores how and what we remember and forget, and how the prevalence of mass-produced imagery distorts and devours our personal memories.

Ahead of his solo show with Ochi in Focus at Frieze Los Angeles, Okokon discusses his visual and sonic sampling, what it means to memorialize materials that are made to be discarded and how he makes a painting move.

Livia Russell Tell me about your new work for Frieze Los Angeles.

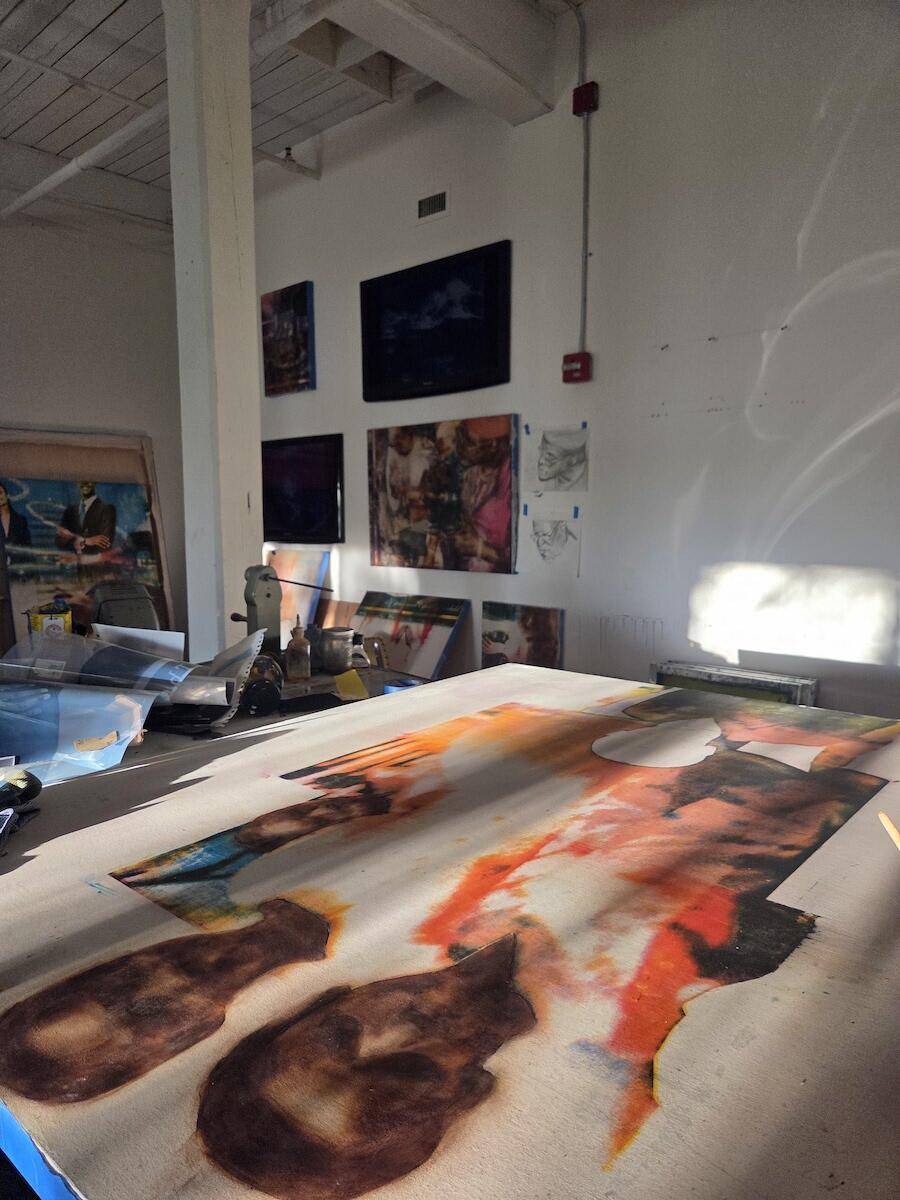

Africanus Okokon I’m super-excited to share this new body of work. It’s a series of paintings, works on paper and a video piece that are all interconnected. Each piece evolves out of the previous piece in a way that’s organic. The two-channel video speaks to the paintings and the works on paper. It’s a complete closed loop of works.

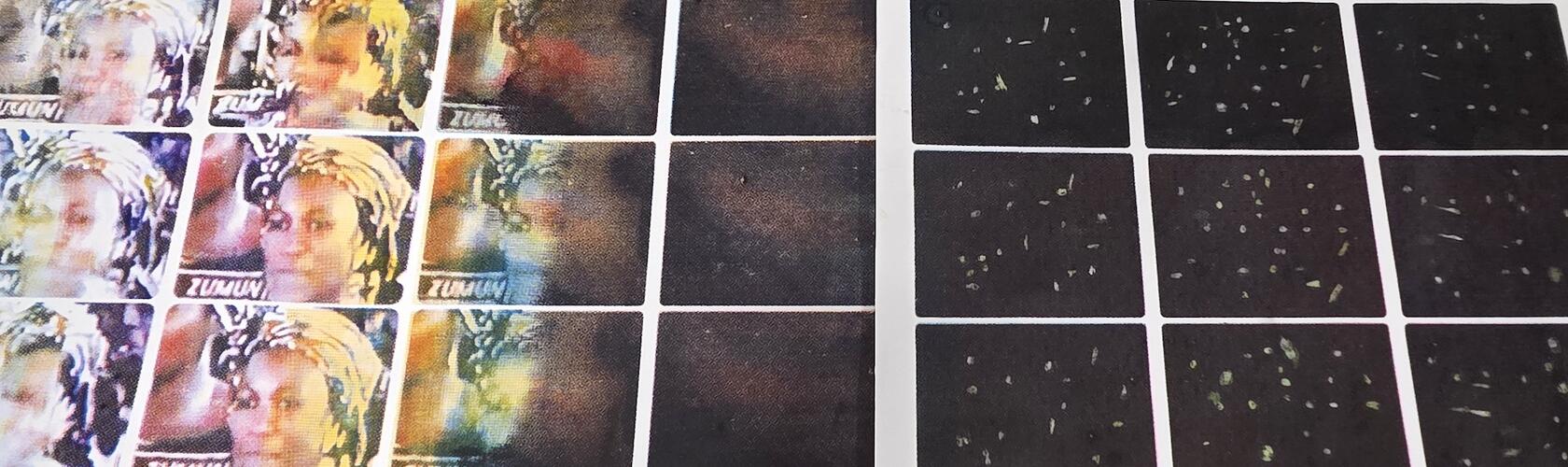

LR Your latest paintings combine silkscreen, coconut milk and collage. How did you develop this unusual process?

AO This is the newest iteration of a process that has been in development for a long time. The materials of the paintings are silk screen, ink, oil and coconut milk that I burn to trigger the Maillard effect, which is a chemical change in organic material where sugars and proteins are chemically reorganized, resulting in browning. The longer I hold the heat gun to the surface, the darker the material becomes.

I paint from photographs, but not in a way that’s neutral. I’m really thinking about the copy versus the original. We have grown up in a world where we’re told that the photograph represents a certain truth. But it’s not a full truth; it’s only a ghost of a lived experience. It doesn’t encompass the totality of our senses, and even our senses are imprecise. The Maillard effect feels intimately linked to photography because the marks aren’t applied. They emerge through this burning process. I’m not drawing with milk or painting with milk or photographing with milk. It’s a passive transformation, the same way that when you develop a photograph you’re not drawing with light. I’m a painter who rarely picks up a paintbrush and a filmmaker who rarely picks up a camera.

I spent a long time figuring out how to use the coconut milk most effectively. I landed on coconut milk because it browns in a way that’s much richer than any other type of milk I’ve tried. It’s a material that speaks to blackness, source, trade and identity. Coconut milk is emblematic of West Africa, but the plant is not actually native to that area. It was brought there through trade with the Portuguese. This continental movement of the material is an interesting history to work with.

LR How do you use printed material in your paintings?

AO I often make certain rules for myself when I’m building a body of work. One rule I made for myself with this series of paintings is that all of the source material needed to come from some type of physical, printed media. The photographs that I’m pulling from are from family albums my uncle gave me a couple of years before he passed away. I brought them back to the US from Ghana.

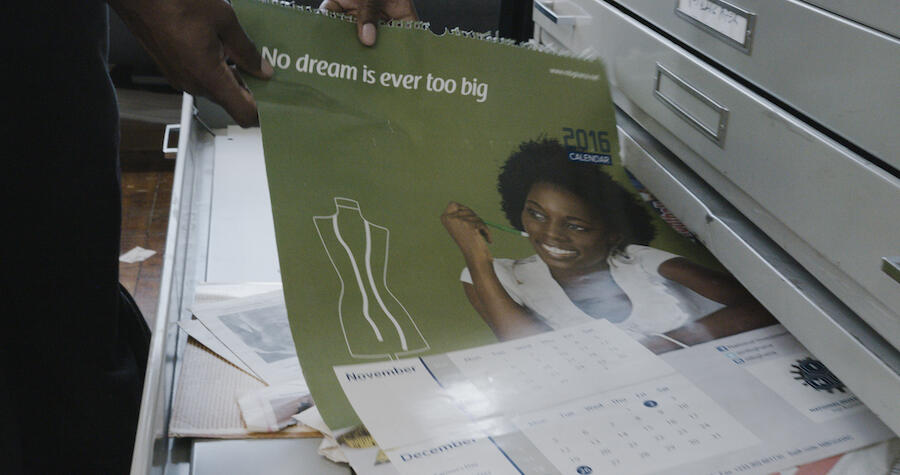

The printed material, such as the advertisements, is all from mass-produced media centring on the continent of Africa, but made for a diasporic – or aspirationally diasporic – audience. I’m thinking through my family’s legacies and how these images travel. I’m the first generation of my family to be born abroad.

We’re inundated with images all day, every day. How does mass-produced content leak into our lived experiences or alter the way that we remember them? I keep all my junk mail. My basement is full of boxes of saved packaging, newspapers and mail – all material that might find its way into an artwork in the future. Mass-produced images are made to be forgotten immediately. They’re made to go from mailbox to eyeballs to trash. I’m interested in what it means to keep these materials and memorialize them.

LR How do you choose an image to work from? Is it for its contextual anchor or its potential for encounter with other materials?

AO How I select images is pretty intuitive. I look at the family photographs and really meditate on them. I’m not just trying to illustrate each image. I’m trying to extract something from it. When I look for mass-produced images to pair with these photographs, I’m thinking about the harmony or dissonance that happens during that encounter. Collage is putting two disparate things in proximity so that something else emerges. The mass-produced images I’m sampling are estranged from their context. A new context begins when the viewer starts to decode the images with their own lived experience, own mood and own particular set of conditions.

What might an image of forgetting look like? I’m interested in collapsing time periods into one surface. That’s how memory and forgetting works. We don’t store memories in computer folders. We just try to recount something from this cloud of what we have.

One thing I noticed after I had made this body of work is that all the advertisements that I selected have time somehow embedded in their language. One 2016 bank calendar says No dream is ever too big. Another ad says If you weren’t spoiled as a child, there’s still a chance. They’re all selling this intangible, potential future. You’ll see this text in the paintings.

These advertisements will feel very different at Frieze Los Angeles to how they feel in my studio. I’m interested in that transformation. Los Angeles has such a rich history of artists – Robert Heinecken, Mark Bradford, John Baldessari – using material from mass media.

LR Does your relationship to the personal photographs change as you paint them?

AO Once you depict a photograph in a painting, it stops describing a situation or a memory or a moment, and it turns into something else. I see finished paintings as completely different objects, even though they’re drawn from photographs. Robert Heinecken describes photographs as ‘objects about something’, not images of something. The way I see the photographs hasn’t changed, because they remain their own contained thing.

I apply a CMYK silk screen to parts of the photograph, I paint parts, and I use the Maillard process of the coconut milk on other parts. Even the CMYK is imperfect and the colours are all wrong. They look nothing like how they look in the photograph. The painting comes in and starts commenting on the peculiarity of the applied material.

LR As the photograph disappears, your painting emerges. How does it feel to navigate this process of addition and subtraction?

AO It felt very generative. When a painting feels like it’s moving, when it feels unstable, when it feels like it’s about to change into something else, that’s when I can step away from it. This transformation is also happening in my video piece Give the picture (2022/26) that will be at Frieze Los Angeles. The video consists of photographs from the photo albums that are turned into fleeting moving images, mass-produced 16mm films that I’ve hand-processed, painted on, scratched and rescanned as an animation, and videos filmed off a television screen, which have been reprinted and re-photographed. It was important in the process of making this video piece that – like with the paintings – every single image has had a physical form before you see it on the screen. You’ll see the source images from the paintings, but they will instantly disappear, return and vanish again. It speaks to how we remember or forget things, like when something’s on the tip of your tongue and it feels like it has gone somewhere else.

The sound in the video is sourced from a cassette tape that was found in the same room as the photo albums. That sound has been transformed, looped and processed into something completely different. When I was working on Give the picture, I was listening to a lot of minimalist and post-minimalist composers, like Terry Riley and Julius Eastman, as well as techno, dub and house. These very different types of music had a similar effect on the psychic state. Time disappears when you’re listening to a piece of music that has that type of repetition.

LR Tell me about the daily rehang of your presentation at Frieze.

AO The paintings are all different versions of each other. In order to remember how the air felt that one day, you might have to forget what your friend was wearing. That’s what I’m trying to communicate with the images. The paintings will change each day at the fair, and the works rehung in their place will speak to the ones that were hung there before. My works on paper are frames from the video, each one representing one second from the video.

LR You began Give the picture in 2022, when you were at NXTHVN art centre in New Haven. What was your experience of NXTHVN?

AO NXTHVN was a great place to make work. I was there right after graduate school. When you’re part of an academic cohort, people are constantly seeing your work and giving you feedback. It’s difficult to sustain that after you graduate. Often, you have a close circle of people that you trust to look at your work, but the work is largely made in a vacuum. At NXTHVN, it was really helpful to have eyes constantly on my work, informing me about how people are perceiving it. There was a lot of freedom to try new things and to experience my work in ways that I wouldn’t have otherwise been able to experience. While I was there, Give the picture was installed in the basement space of Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. I’d never seen my work at that scale. At Frieze, the piece will be on two monitors. I’m interested in how that might feel different; they’ll be almost person-size.

LR As an interdisciplinary artist, you’ve described your studio as a ‘machine’. How do you work across moving image, sound and painting?

AO Right now, the studio feels really generative because I’ve started to work on music for another upcoming piece at the same time as finishing these paintings. It feels very freeing to jump from making something with a sampler and my headphones for a few hours, then painting, then testing a video work. I triangulate those three processes to see how they are all interconnected.

Further Information

Frieze Los Angeles 2026, 26 February – 1 March 2026, Santa Monica Airport.

Limited full-price tickets are available now, or become a Frieze Member for priority access, multi-day entry, exclusive guided tours and more.

For all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to the newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram and Frieze Official on Facebook.

Main Image: Works in progress in Africanus Okokon’s studio. Courtesy: the artist