The Artists Challenging Taboos to Start a Conversation About Suicide

Niall McCarthy, Hannah Perry and Lauryn Youden use first-hand experiences of loss to critique the systems that can contribute to mental health crises

Niall McCarthy, Hannah Perry and Lauryn Youden use first-hand experiences of loss to critique the systems that can contribute to mental health crises

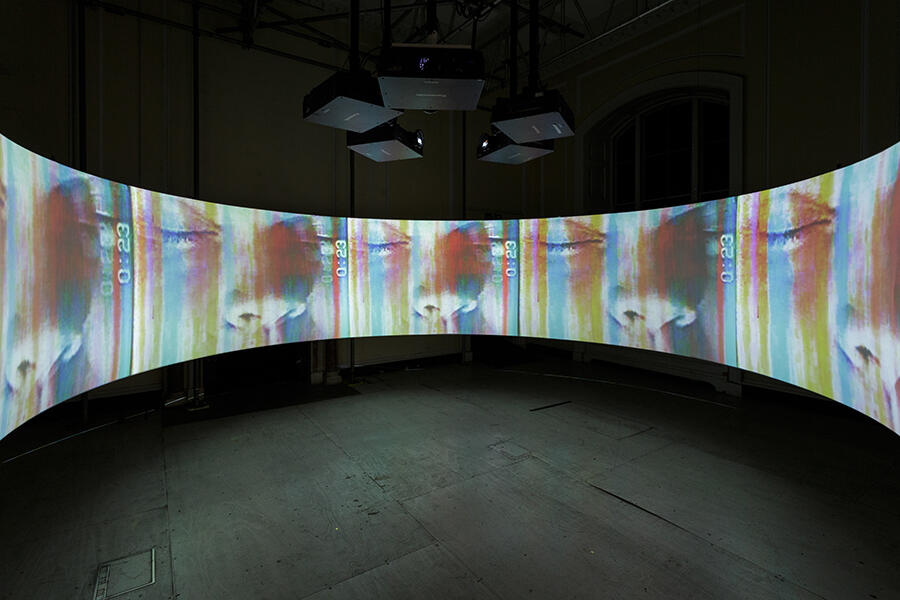

In her 2018 exhibition ‘GUSH’, Hannah Perry presented a fragmented view of the body. Using footage from a custom 360-degree camera, the British artist immersed audiences in contorted physical movements, accompanied by a distorted spoken word track and an instrumental score. The show, at London’s Somerset House, grappled with grief and trauma, exploring the entangled position of a mind and body under pressure. The work was created after the suicide of her friend and collaborator Pete Morrow, and its spoken aspects were infused with his poetry. ‘It was a nice way to incorporate him; we still had this communication,’ says Perry, who was keen to examine the wider failing support structures that impact suicide deaths at a time of austerity. In the years since, rates of suicide in the UK have only continued to increase.

Art history is loaded with works that romanticize a narrative of tortured, suicidal creatives, such as Henry Wallis’s The Death of Chatterton (1856), in which the teenage intellect Thomas Chatterton is sprawled across his bed in a sun-dappled final repose. Many embraced the drama of suicide through mythological tales and literature, from Joseph Wright of Derby’s shadowy impression Romeo and Juliet: The Tomb Scene (1790) to Charles Mengin’s gothic painting Sappho (1877), featuring the Greek poet who leapt to her death after an unrequited love. The few contemporary artists who tackle the issue challenge common misconceptions of suicidal people simply losing control. While they may make work from a personal position, whether through a loved one’s suicide or after experiencing suicidal ideation themselves, they also highlight the broader systemic failures that for some can make living feel impossible.

Perry notes how limited public resources were in the UK at the time of Morrow’s death, with years of austerity leading to the disappearance of much-needed help. ‘When we’re thinking about people who can’t see a way out, it’s impossible not to talk about the social and economic ramifications of what we’re living through,’ she says. ‘Resources at the time seemed fucked up, but now, almost ten years later, it really is in dire straits.’

When the exhibition opened, Perry spoke about the role of masculinity in driving suicide. Government statistics show that approximately three-quarters of suicides in the UK and nearly 80 percent in the US are male, a fact often attributed to men being less likely to ask for help and feeling pressured to ignore vulnerability. Perry feels it’s important to look at the heteronormative structures that drive gendered positions on both sides, whereby women are encouraged towards heavy self-critique and sacrifice to the family structure, and men towards repression of feelings and providing at all costs. ‘These gender biases don’t help anyone.’

Niall McCarthy’s father killed himself when the Irish artist was 15 years old. He began to untangle this experience in his painting in 2023, with Father Lying in a Wheat Field. The work transposes an image of his father’s face in the funeral home onto the rural setting in which he worked as a farmer, and where he died. McCarthy was inspired by Nan Goldin’s 1989 image of her friend Cookie Mueller in her casket: ‘My work up until that time had been looking at landscapes and empty fields. Seeing that photograph made me wonder if I could take a leap and put my dad’s face into the work.’

McCarthy draws upon surreal iconography to capture the disbelief surrounding suicide and his father’s turbulent connection with the landscape. In Requiem (2024), the artist clutches his father, who bears a subtle gunshot wound and is surrounded by bullet casings, with details taken from the coroner’s report and the composition informed by Ilya Repin’s Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581 (1885). In Synthesis (2023), his father’s image crumbles from a rockface and slips into the sea, while Bedroom at Dawn (2025) borrows its pose from one of McCarthy’s last views of his father, as he leant against the window the day before he died. ‘It’s a recurring image of him that’s hard to leave,’ the artist says.

Farming is brutally hard, both physically and emotionally. By placing his father within the landscape, McCarthy draws attention to this pressure. His paintings also analogize his father’s death with the ecological erosion that dissolves the land surrounding the family home. The works confront the religious and masculine ideals that were prevalent at the time, two decades ago, in Ireland. ‘Society was very conservative,’ McCarthy tells me. ‘When you don’t have a diagnosis, you’re fumbling around in the dark. There was no way he was going to tell the GP how he felt. I didn’t feel angry with him. I felt much more let down by the society of the time that he couldn’t be helped.’

Lauryn Youden likewise confronts the structures that can push people away from community and towards suicide. The Canadian artist’s works are created within the wider context of her chronic illness and disability. She is wary of artists using suicide as a ‘cheap trick’ in their work, highlighting the dangers of exploring this subject without providing critique of the ableist, capitalist systems that impact it. Youden’s grandmother died by suicide, and she witnessed a shame passing through the family, taking shape in a misogynistic view of women dealing with mental illness.

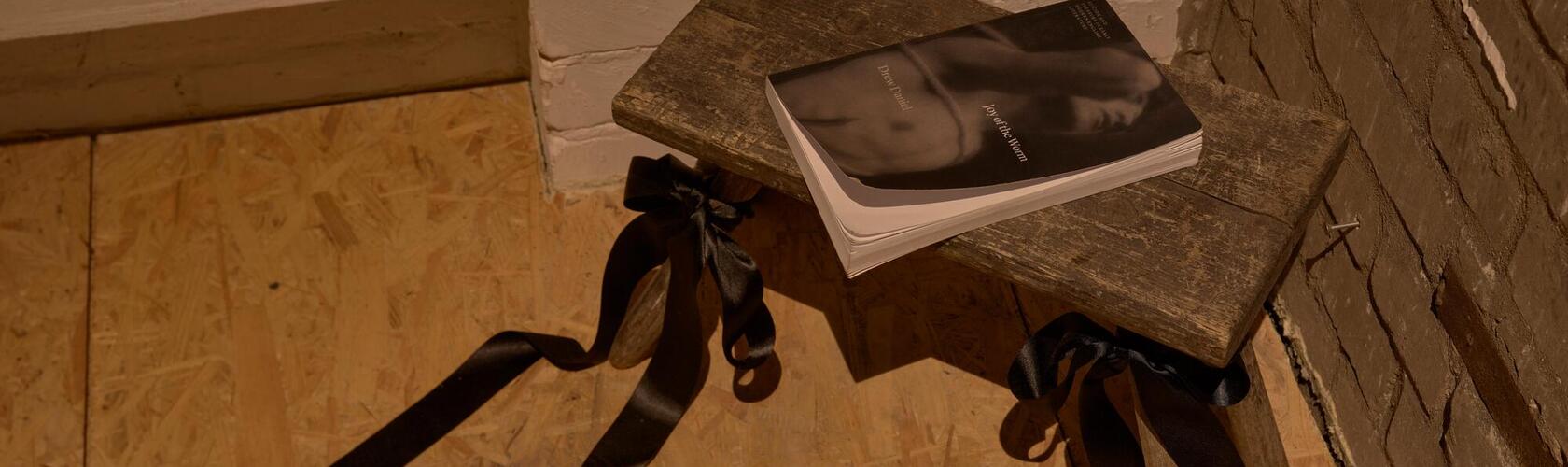

Her recent exhibition ‘Even a Worm Will Turn’ (2025) at Number 1 Main Road in Berlin was inspired in part by Drew Daniel’s book The Joy of the Worm (2022), in which the writer explores early literary examples of self-killing, where humour, camp and romance are not additions but essential tonal structures that shape how the act is understood. ‘Shakespeare used techniques that allow the audience to experience a range of emotions. [In his plays], we witness intense things that are a part of life, that many people don’t want to face,’ Youden tells me. She utilizes the camp visual aesthetics of her work to disarm the viewer, making use of ribbons, tulle and glitter alongside medications and gifts that embody the support network that has kept Youden alive. In ‘Even a Worm Will Turn’, a black rope embellished with pink ribbons hung ominously over a battered copy of Daniel’s book.

‘I’ve been careful not to romanticize mental illness in my work,’ Youden says, ‘but being stuck with one single view really limits or cuts us off from survival mechanisms, and one of those is humour. That’s why there are these subtle winks in my work: not to make light of a serious topic but to show that joy and humour can be found in dark places. It’s critical to recognize them for what they are: tools for survival.’ Youden’s unconventional approach draws on films such as Midsommar (2019), which presents two polarized visions of suicide – the first, when the protagonist’s sister kills herself and her parents; the second, when two elders choose to jump from a cliff as part of a community ritual – against brightly coloured visuals and a pastoral setting. Through her use of camp embellishments and humour, Youden aims to open a space in which talking about suicide is less frightening and questions can be asked about mental health. ‘Having the topic become more approachable allows for an interdependency to build,’ she says. ‘I believe there is always some level of support people can provide, but if they’re too intimidated or overwhelmed by the situation, it keeps mutual support from taking shape.’

Main image: Lauryn Youden, ‘Even a Worm Will Turn’, 2025, exhibition view, Number 1 Main Road, Berlin. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Eric Tschernow