The Rich Film Heritage of Central Asia

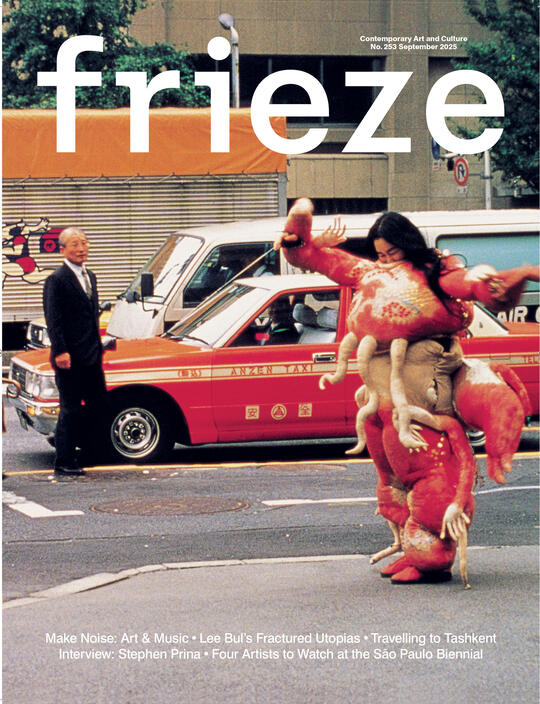

Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt revived a groundbreaking Uzbek film festival, reflecting on how its Cold War–era screenings bridged global cinema and fostered south-south solidarities

Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt revived a groundbreaking Uzbek film festival, reflecting on how its Cold War–era screenings bridged global cinema and fostered south-south solidarities

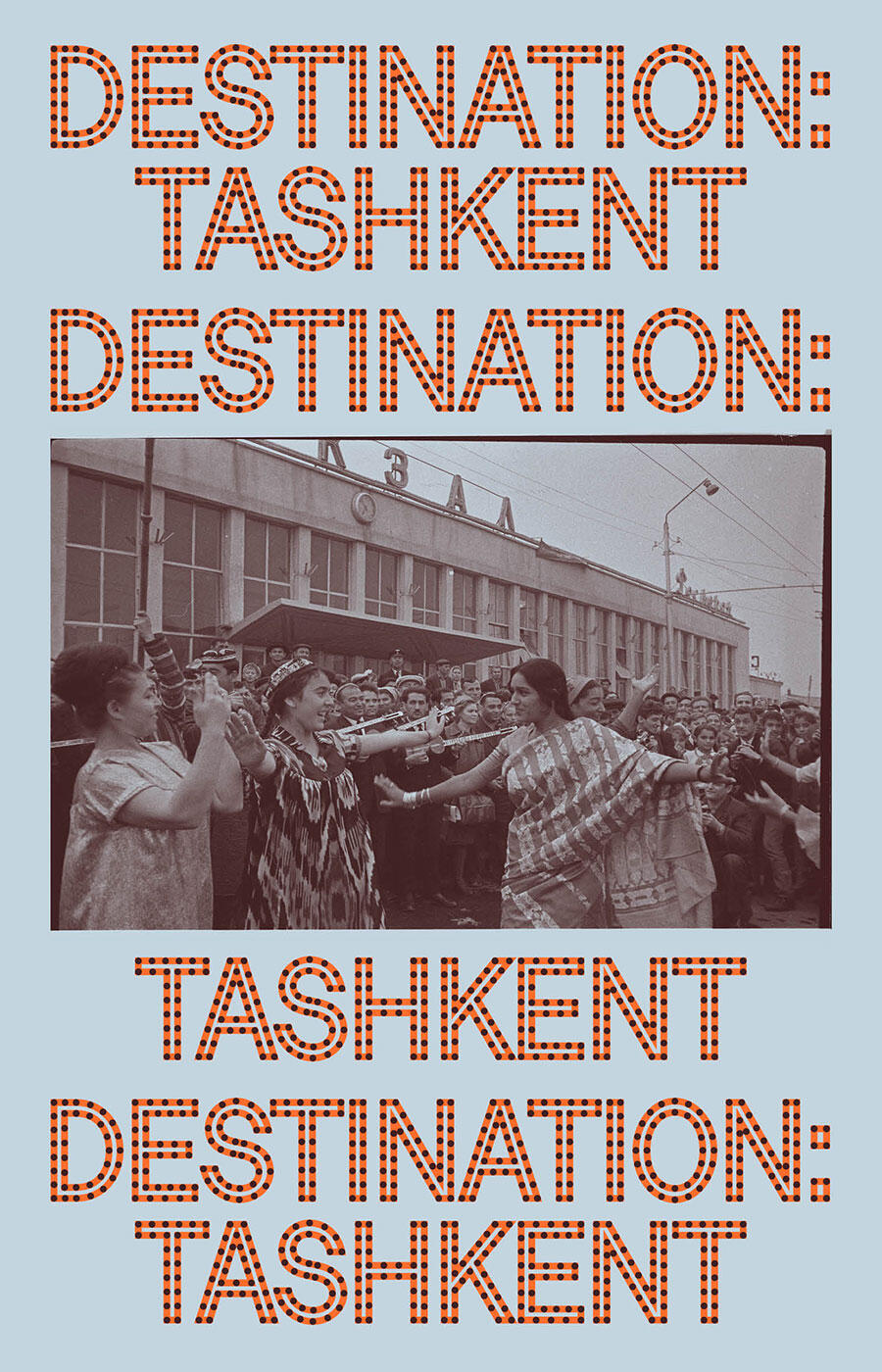

The images are as fascinating as the anecdotes. In one black and white photograph from 1978, nine women are gathered outdoors in sunny Bukhara. The caption reveals that the women are ‘participants of the Tashkent Festival for Asian, African and Latin American Cinema’, which was held annually from 1968 to 1988. Like the many myths that perpetuate the festival’s legend, these images of transcultural sociability document glimpses of what unfolded at the sidelines of an event held, in the words of its slogan, to promote ‘peace, social progress and freedom of peoples’. In late 2023, with the help of our brilliant colleagues at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin, we began working on ‘Destination: Tashkent’ – a film festival, public programme and publication project that celebrated and critically examined the legacy of this legendary event.

We were interested in exploring how the original festival navigated ideological strictures to emerge as a unique platform for promoting anti-imperialist and anti-colonial ideas via popular cinema. We also wanted to understand how filmmakers from Asia, Africa and Latin America engaged with audiences during and after the film screenings in Tashkent. The festival, which Uzbek filmmaker and former participant Ali Khamraev described as ‘a celebration for the whole city’ in a conversation published in our co-edited bilingual (English and Uzbek) companion publication Destination: Tashkent Reader (2024), became an important arena for cinematic internationalism and dynamic interactions – not least due to its location in the Uzbek capital, which was itself still grappling with its own relatively recent, (semi-) colonial positioning within the Soviet Union. In three research trips to Uzbekistan between 2023 and 2024, there was plenty to discover about the festival and the internationalist film networks it fostered.

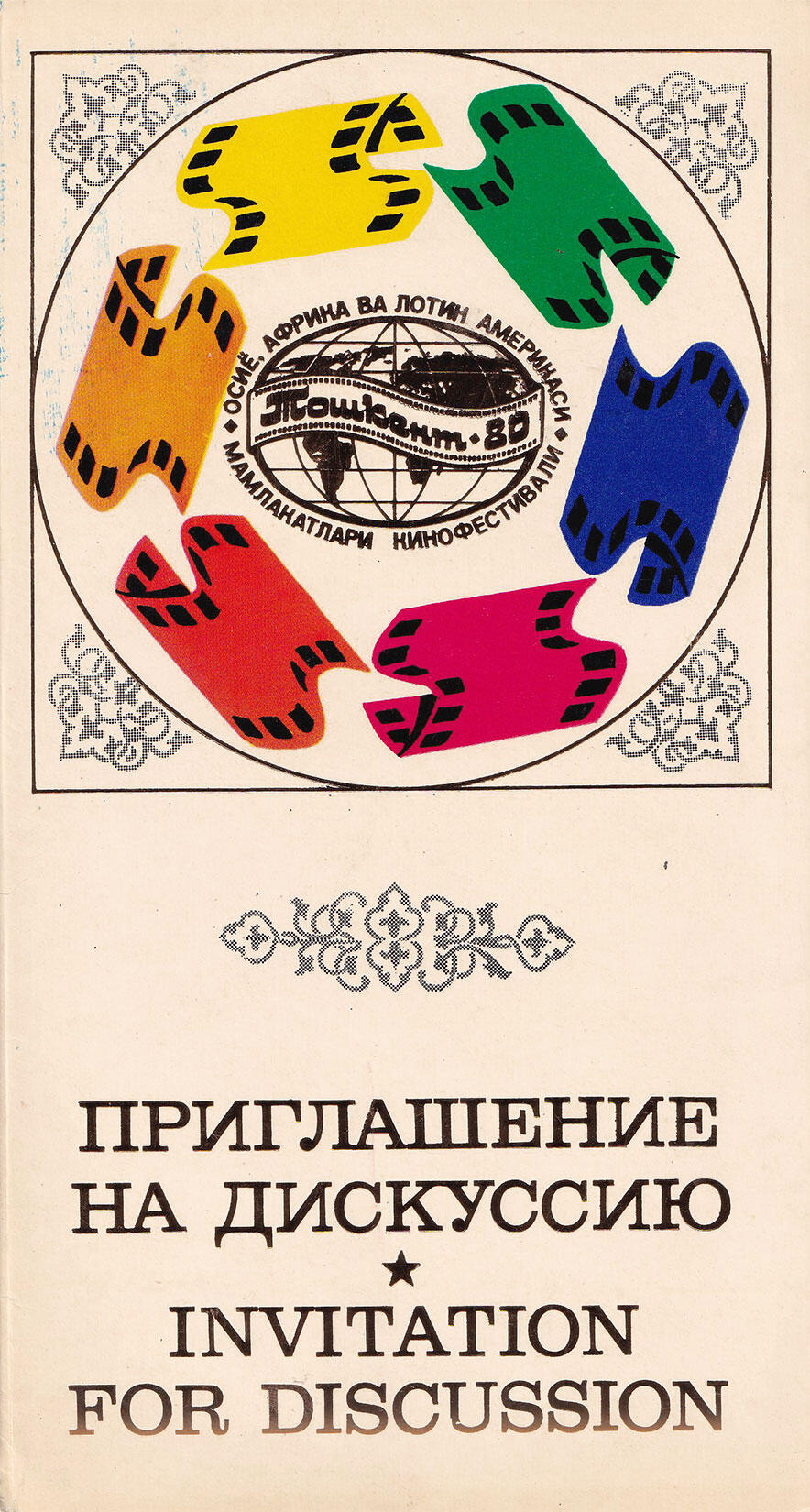

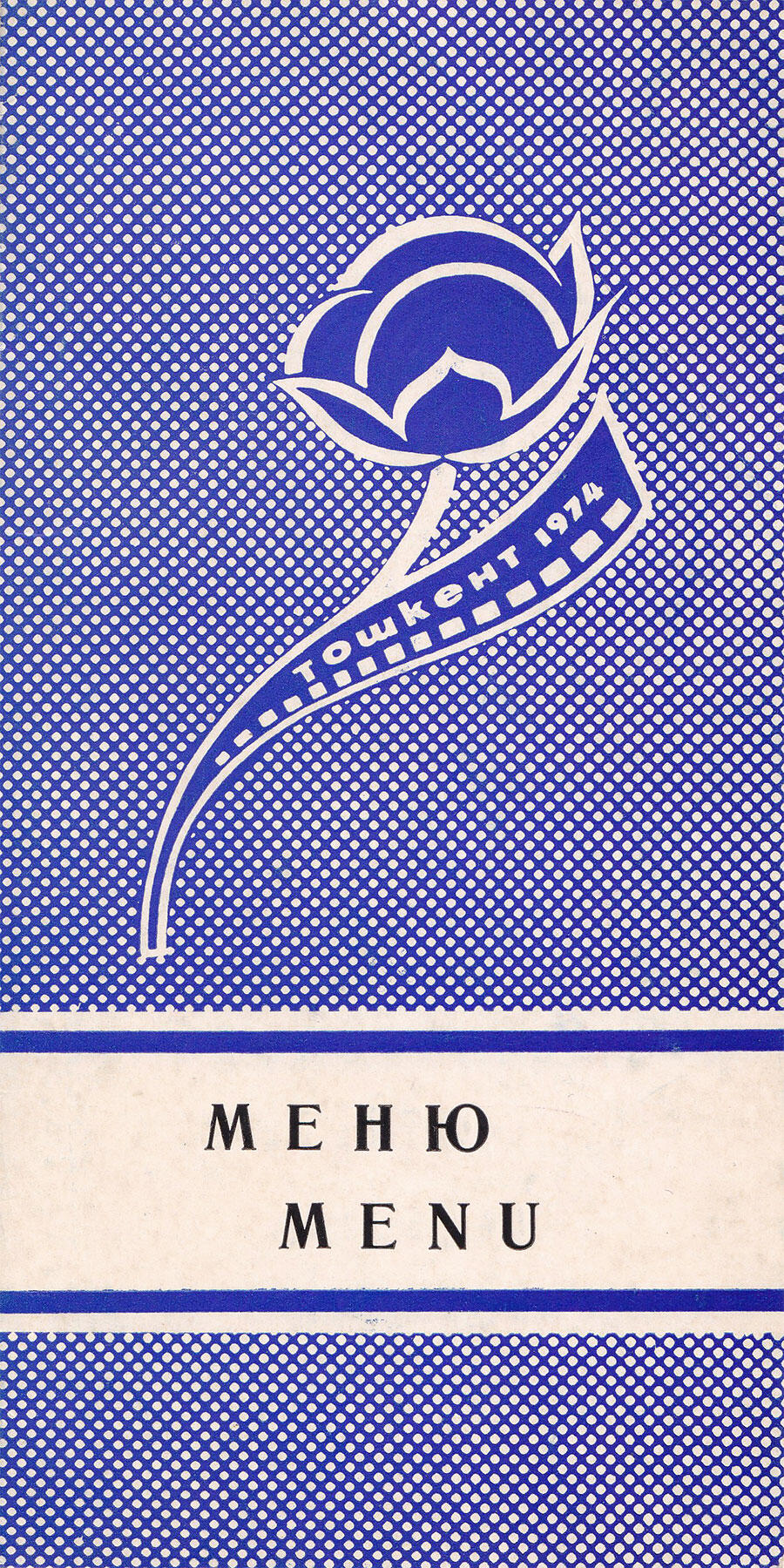

At the Cinema Palace Museum in Tashkent, the festival archive contained photographs, magazines and assorted ephemera, including invitations to collateral events, such as an ‘Africa Liberation Day’ commemoration, or excursions to Samarkand or Bukhara, as well as dinner menus, merchandise and souvenirs. We featured a selection of this material in Destination: Tashkent Reader, which visually highlights the convivial nature of the festival described by many contributors to the book.

Yet, despite these positive accounts and the event’s ideological framing, Khamraev told us that the rooms at Hotel Uzbekistan, where all participants were accommodated, were bugged by the KGB. One of the few alternatives to a western-style format, the Tashkent Festival facilitated trans-continental networking and solidarity-based alliances between filmmakers from the three featured continents. This was especially true in cases where films that had been banned in both ‘first-’ and ‘third-world’ countries – Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène’s Mandabi (1968), for instance – were shown in Tashkent, making the festival a place of intellectual and artistic refuge. Many other leftist filmmakers – including Goutam Ghose, Med Hondo, Miguel Littín and Mrinal Sen – were also present in Tashkent and played a significant role in fostering the event’s internationalist ideals.

Today, despite significant challenges, Tashkent has a vibrant and growing community of artists, filmmakers and creatives.

One key element of our engagement with this legacy was the festival’s translation practices. We were curious about their role in transcontinental dialogue and, by extension, in what might be termed south-south solidarity. At such a multilingual event, translation was a particular challenge, as only a few films were subtitled. ‘Subtitles were very unpopular in the Soviet Union,’ Khamraev confirmed in the aforementioned interview. ‘No one wanted to read in the cinema.’ Thankfully, the festival’s comprehensive approach to translation ensured that locals were able to enjoy the programme, with the organizing team providing live translations into Russian via loudspeaker, as well as into English, French and, later, Spanish and Arabic via headphones. As historian Elena Razlogova notes in her contribution to Destination: Tashkent Reader, the translators redefined the films by delivering live performances over the original soundtracks. Even those visitors who did not understand any of the official festival languages were accompanied by interpreters who spoke Bengali, Khmer, Wolof and more.

Aware that the festival was largely shaped by the political agenda of the Soviet Union, we were keen to hear from the current generation of Uzbek filmmakers, curators and cultural workers, many of whom happen to be the children of translators who worked at the event. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the state-sanctioned history of the Tashkent Festival, as officially recounted at the archive of the Cinema Palace (Kinochilar uyi), quickly unravelled when we spoke to present-day film professionals working in Uzbekistan. Producers, directors and curators alike were openly sceptical of attempts to reprise the festival’s larger-than-life legacy. Instead, they are focusing on cultivating local networks through entirely new approaches – especially in the face of decades of authoritarianism.

Today, festivals such as Cinema Love provide a more sustained and intentional focus on the Central Asian region, with no ambition to become the next Tashkent Festival in terms of geographical scope. By contrast, we found that Berlin-based, diasporic film professionals from Asia, Africa and Latin America were keen to create connections across their respective regional networks, actively supporting each other’s community film festivals.

The programming for ‘Destination: Tashkent’ built on the original festival’s contested legacy by not only showing films, but also examining the political, cultural and historical contexts of these encounters. This discursive space was created through shared meals, music and performance interventions that accompanied the film screenings, as well as through the publication, which enabled a deeper engagement with the oral histories around the original festival from filmmakers present, such as Khamraev. For instance, curator Marie Hélène Pereira’s conversation with Malian director Souleymane Cissé, also included in Destination: Tashkent Reader, was conducted only a few months before his death earlier this year at the age of 84. These filmmakers vividly brought the Tashkent Festival to life through their energy, passion for filmmaking and the countless anecdotes they shared.

Hanna Wiedemann / HKW

Within the framework of ‘Destination: Tashkent’, we collaborated with spaces across the Uzbek capital that bring people together through a shared love of cinema. The project launched last September at Goethe Institute and MOC Hub, which has quickly become a vital gathering place in the city for those who not only appreciate film, music and art, but also value dialogue and conviviality. A four-day programme of screenings, panel discussions, keynote talks and culinary offerings connected Tashkent’s local film scene with visitors and participants from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The programme was complemented by a curated city tour, which traced the footprints of the original Tashkent Festival across the urban landscape. Participants could also visit Tashkent Film School, where workshops and educational programmes play a key role in nurturing young filmmakers, with a special focus on empowering women in the industry. In addition to these venues, spaces such as 139 Documentary Center – which hosts the NOMSIZ Festival for experimental film from the region – enrich Tashkent’s cultural landscape with exhibitions, film screenings and various talks programmes. Today, despite significant challenges such as censorship and a lack of financial support, Tashkent has a vibrant and growing community of artists, filmmakers and creatives, who will receive even greater international visibility when the inaugural Bukhara Biennial, ‘Recipes for Broken Hearts’, opens this month.

In his essay for Destination: Tashkent Reader, ‘The Myth of Tashkent: Weaving Solidarities and the Politics of Film’, HKW director and chief curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung writes: ‘One can say that the Tashkent Festival, at a time when one of the most important film movements of the 20th century, Nouvelle Vague, was looking towards the north and the west, decidedly looked towards the east and the south.’ At HKW, ‘Destination: Tashkent’ came hot on the heels of ‘Echoes of the Brother Countries’, an exhibition and research project dedicated to the often-overlooked political, economic, educational, artistic and migratory exchanges between the GDR and other socialist states – the so-called brother countries – particularly Angola, Mozambique and Vietnam.

In both ‘Destination: Tashkent’ and ‘Echoes of the Brother Countries’, the iconographic depictions of solidarity portrayed under the banners of ‘united class struggle’ or ‘socialist internationalism’ hid other realities with which historians are only slowly beginning to grapple, even as their cultural ramifications were comprehensive enough to provide HKW with more than a year’s worth of research and programming. We were consistently fascinated by the untold stories we discovered and the floodgates that opened when we asked questions about people’s experiences in the context of these overarching epochal narratives. In the end, we grappled with more than could possibly be covered by a single project. ‘Destination: Tashkent’ was only the beginning – more must follow.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 253 with the headline ‘Destination: Tashkent’

Destination: Tashkent – Reader is available via Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) and Archive Books

Main image: Tashkent International Film Festival poster (detail), 1986. Courtesy: National Archive of Cinema, Photo and Phono Documents of the Republic Of Uzbekistan