Mariana Teixeira de Carvalho on Collecting: ‘Enjoy It’

The Brazil-born Londoner, whose collection includes Sonia Gomes, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Lubaina Himid and Cildo Meireles talks to Alessio Antoniolli

The Brazil-born Londoner, whose collection includes Sonia Gomes, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Lubaina Himid and Cildo Meireles talks to Alessio Antoniolli

Alessio Antoniolli We first met when you moved to London, maybe 12 or 15 years ago. We met through artists and I think we both live our lives surrounded by artists. Does collecting for you start with the artist or with the work?

Mariana Teixeira de Carvalho For me, everything starts with the artist. It can also start with the work, which takes you to the artist, who then leads you back to the work. Sometimes you just get into the work before knowing anything about who made it. A lot of people say that you have to dissociate the person from the artist, but it’s very difficult to do that – especially if they are your contemporaries. For me, it’s about knowing that some people have a long journey ahead of them, and wanting to be a part of it, wanting to help them realise their potential.

AA A good friend of ours, who is also a collector, once said to me that going into an artist’s studio is like going inside an artist’s head. When you visit a studio, what questions do you ask?

MTC Every practice is different; every personality is different. You have artists who are outspoken, while some are extremely shy; some hate to talk about their work, and some have a formula at the ready; some have pristine studios, almost like showrooms; other studios are small and messy. Sometimes there isn’t a lot of work to see, but you just want to get inside their heads. I allow them to take the lead.

AA You’ve been invited into an intimate space, after all.

MTC I’ve got a very old-school way of collecting. The work has to mean something to me. The practice has to resonate in some form. Although my interests may shift, I have never sold anything in my collection. It’s not that it is wrong to do so: sometimes you want to oxygenate what you’ve got, or the works don’t mean as much to you any more, or you haven’t got enough physical space and so they have to have a second life somewhere else. But so far, my selection still makes sense and still ‘fits’ me.

AA Your background is in law, but you then went on to work for renowned galleries: Luisa Strina in São Paulo, and Hauser & Wirth and Michael Werner Gallery in London. What led you to art?

MTC It wasn’t a rational decision, it happened organically. I think the way that some artists can tackle a topic in such a focused way, for me correlates to law. Artists can tackle difficult topics in a subtle, very precise way, and shed light on unpleasant or uncomfortable subjects very effectively. Art is a vehicle that can invoke empathy in a way that is non-confrontational and non-aggressive.

AA Absolutely. Art reflects society, but it also has the potential to challenge it and push at the boundaries.

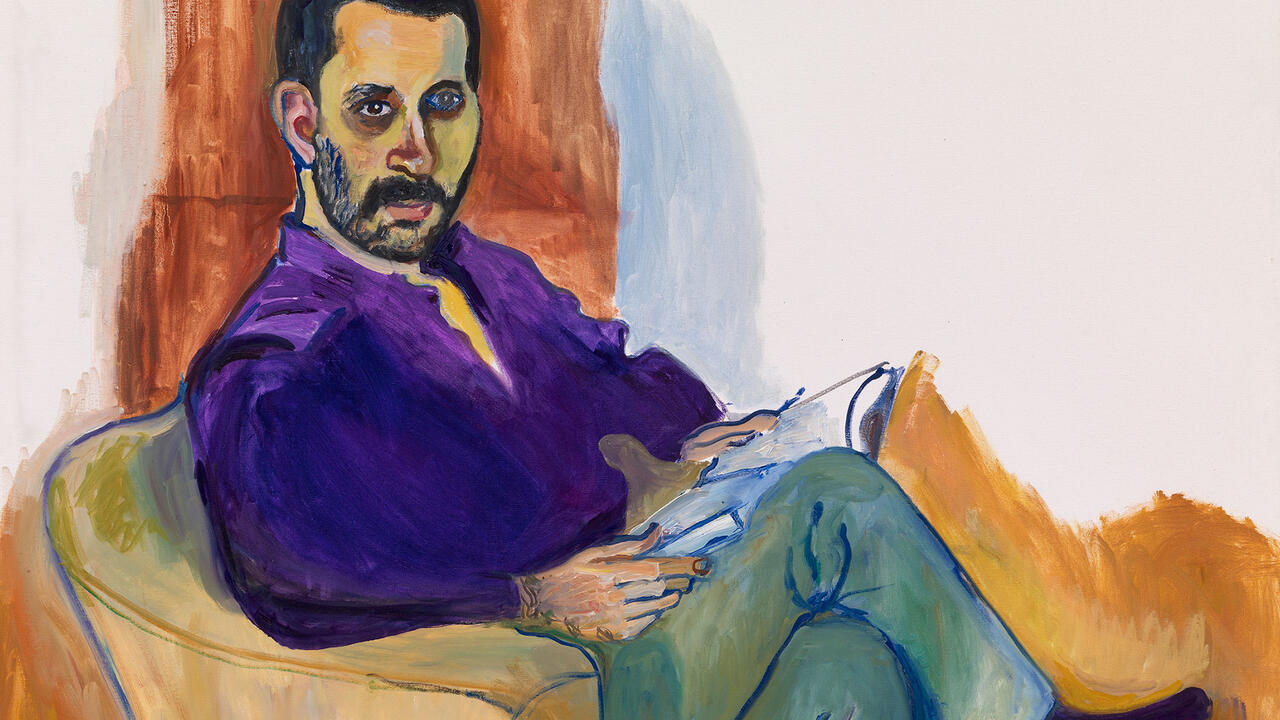

MTC It asks the questions and then leaves it to the audience. I admire artists who do this in a rigorous way. For instance, Lawrence Abu Hamdan. I have a couple of very uncomfortable but extremely powerful works by him. They are very beautiful at the same time as being meaningful. His work has so many layers.

Cildo Meireles is another artist I collect who is also very political, and there are so many ways of interpreting what he’s doing. Then there are others who challenged their times, often through their own circumstances, like Lubaina Himid, Liliane Lijn, Cecilia Vicuña and Sonia Gomes.

AA Do you find you naturally gravitate towards certain types of work, themes or artists?

MTC I’m attracted to people who take very strong positions. I’m drawn to female artists from a particular time in history. I’ve got a lot of works by older women, some of whom are not alive any more, but some who are, and who are still extremely prolific, but it has taken them a lifetime to be recognized. There’s still a long way for the art world to grow and catch up in that sense. It’s changing, but it’s slow.

At the same time, I follow very young artists. You don’t know where they’re going to go, but if I see potential, I’m interested.

AA Which is also part of the beauty, because you are actually supporting them through their career. You can see them grow. You don’t have to like every bit of their career, but you can appreciate their journey, in the same way that you are on a journey as a collector.

In the end, collecting is about your approach to life in general.

MTC It’s important to be open to everything. I’m not a video collector, but I do have a few video works because they speak to me. I leave it completely open.

AA Do you have any pearls of wisdom for collectors starting out?

MTC Maybe don’t be too serious about it. Enjoy it.

AA Enjoy it and follow what makes sense to you.

MTC Respect the process. Respect the artists more than anything else. Try to give them the correct platform. If you want to be part of all this, you also have to be in it for the long run and for the right reasons. You can’t be too rational: you must do your research, know where to go and who to trust, but also remain open to instinct and emotion.

AA With your decisions, how much comes from the heart and how much from the head? Which wins out when you decide to acquire something?

MTC There’s always an element of impulsiveness. You have to respond to the work. You have to think about it again, to keep going back to it. Then it makes sense to pursue it. You also have to be exposed to a lot of things and know what you like. It’s a different process for different people. Some people prefer to work with advisors and get the information already filtered. I don’t, I like to filter it myself.

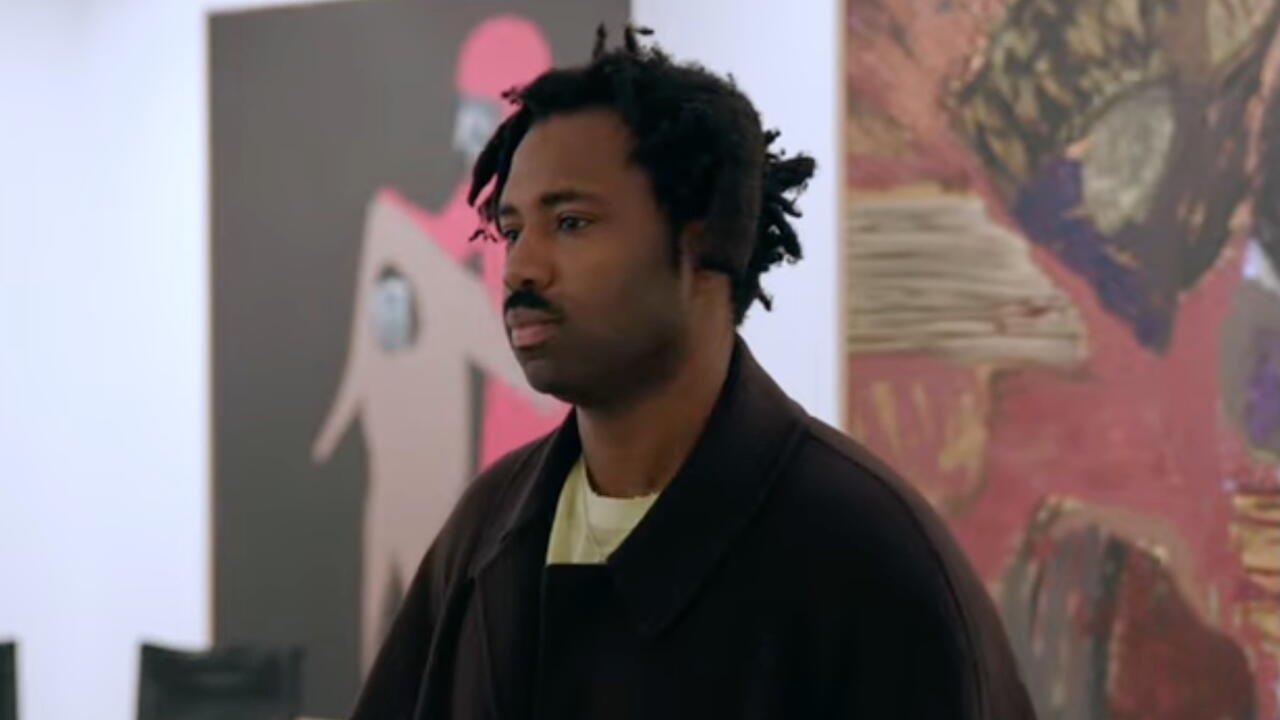

AA It goes back to how we started this interview – that we met through artists and that you live in the art world. You go to galleries, you know artists, you are part of the community.

MTC Exactly. Maybe one piece of advice for people starting out is not to view the art world as segmented. We try to make distinctions between who’s on each side of the equation, but it’s all part of the same whole. There are no good guys or bad guys. Everyone is needed.

AA It’s an ecosystem. You grew up in São Paulo. You’ve lived in New York and London, among other places. Have your travels and the different contexts in which you’ve lived and worked affected the way you relate to art and informed the way you collect?

MTC Absolutely. The reason I don’t stick to a theme or a moment in history is because I’m just too curious. There’s always something else that I don’t know. I’m far from knowing every art movement. I’m very grateful that I’ve had all this experience of visiting and living in different places.

AA I feel very close to the way of thinking that art is knowledge. It’s a way of learning about the world around you and understanding that there isn’t just one way of doing things. I’ve always been attracted to artists because they never choose the mainstream way; they always find the back or the side door.

MTC Also, I think that collecting is not only about acquiring objects. You’re also collecting experiences. That’s become more and more important to me. The last piece I bought was a painting by the late Colombian artist Emma Reyes (1919–2003). Her life was as compelling as the work she made. She moved between many countries, crossed cultures, was an artist, a storyteller, a writer; she loved deeply, broke boundaries. Her œuvre, besides being very beautiful, carries that journey, which is one I somehow share.

In the end, collecting is about your approach to life in general. How much do you actually need to have, and how much do you need to give and give back?

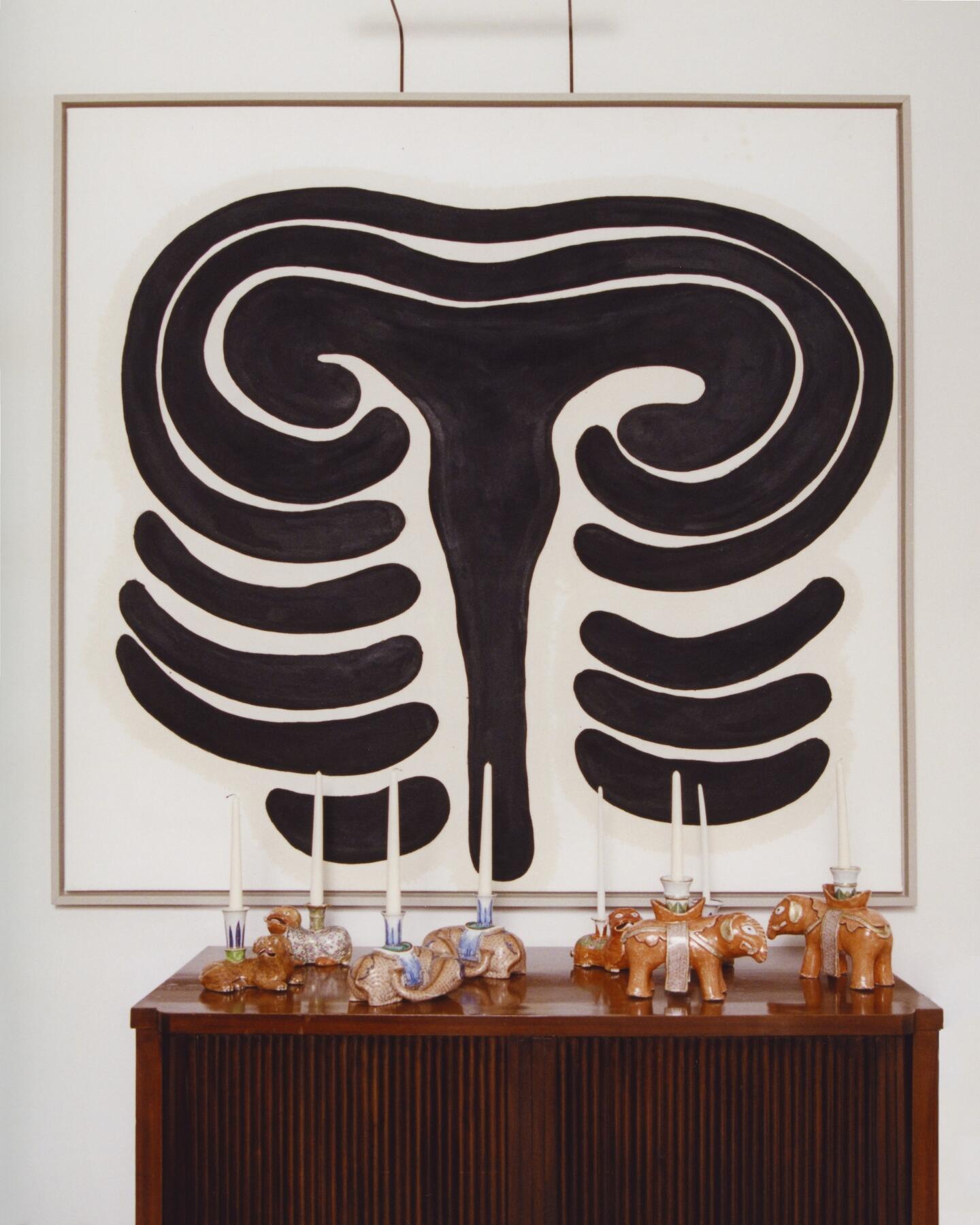

AA Which leads us to the foundation you have recently co-founded with your grandfather, Renato de Albuquerque. It was set up in February this year in Sintra, Portugal, to house his world-class collection of ceramics.

MTC My grandfather collected mostly Chinese porcelain for 60 years, never with the goal of showing it, or even creating a significant collection. He started young with European porcelain when he didn’t have the means to acquire more relevant works. The more he learned, the more he got drawn into one particular moment in history. The focus is very niche: Chinese export porcelain from the 16th to 18th centuries, even though the collection spans from the 16th century BCE.

As a family, we didn’t know how important the collection had become until a few years ago, when we started getting asked about it by specialists.

The cultural value of a collection that has been built up, like this one, over all those years, is far greater than the sum of its parts. If dismantled, it could no longer be put together.

AA It’s the unity that produces the knowledge, that produces the space for research.

MTC Yes, and that’s true of collections in general. In the case of my grandfather’s, it tells the story of trade, of different areas of the world. It tells the story of East and West, of how people lived at that time.

AA I was looking at the foundation’s website and noticed that you talk about a space for research and knowledge. It’s about sharing, because these objects are basically signifiers of history.

MTC They function as artefacts, as well as having artistic value. The painting and the firing, the craftsmanship and the shapes, all of these things combine. It seems a bit ambitious to say that you can help understand the history of the world through ceramics, but you actually can. It was the first art form and we still use it for its decorative value. But it’s also part of everyday life – we eat from it, drink from it. Now people have taken to asking: is it craft, is it fine art?

AA These conversations will go on for ever, probably.

MTC Yes, and we don’t need to define it. We just need to give it the right platform. The public can make their own decision – if it’s one or the other, or both.

AA I think one of the big questions is always how do we make things accessible? What are people interested in? The answer is that it will be constantly changing.

MTC Each collector exists in a particular time. The challenge is how to make a collection from another era relevant to a new generation and to the generations to come. I believe institutions have a duty to help us understand the past, and in so doing, help us not to repeat mistakes. You can do that through art in a much more empathetic and emotionally connective way for future generations. This is what I am trying to do in Portugal and that’s the reason we created an exhibition programme of contemporary ceramics as well as an artistic and research programme.

AA To create entry points.

MTC Yes, but also to give a platform to living artists who are exploring the medium and would like a dedicated space. We don’t ask the visiting artists to respond to the collection, but so far, everyone has shown interest. I don’t share my grandfather’s love of Chinese porcelain, but I truly admire and value its place in history. I believe you don’t need to share the same passion to do something amazing with a collection, as long as you respect and acknowledge the importance that it holds.

AA You’re talking almost as if it has become a responsibility?

MTC I see it as a duty. It’s bigger than you, than your family, and bigger than the person who created it. This collection is much bigger than my grandfather. In the end, I believe it’s an obligation rather than a privilege.

Further Information

For all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to the newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram and Frieze Official on Facebook.