The Ten Best Shows in Europe of 2025

From an expansive sixth edition of the Kyiv Biennial to a radical feminist retelling of digital art histories, these are the exhibitions everyone was talking about

From an expansive sixth edition of the Kyiv Biennial to a radical feminist retelling of digital art histories, these are the exhibitions everyone was talking about

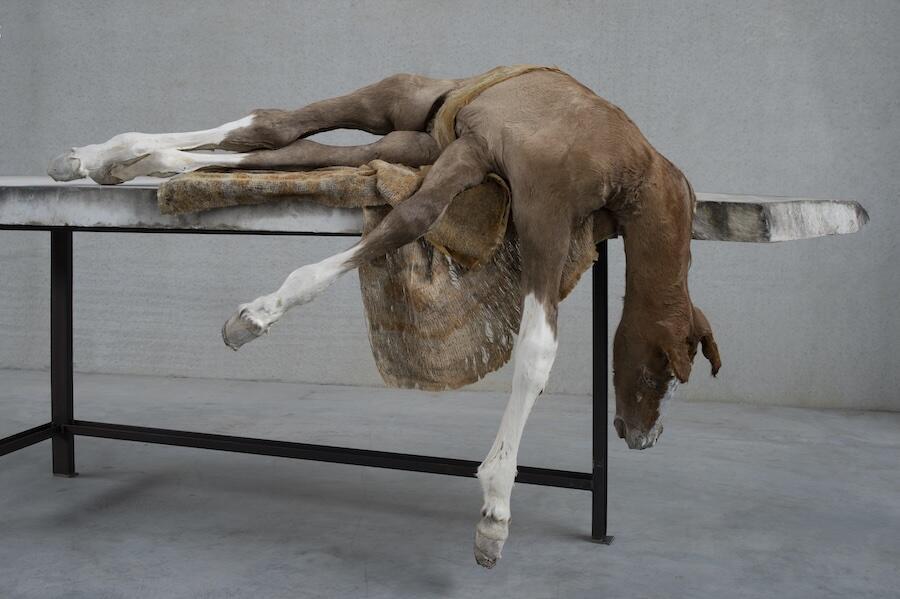

2025 was a great year for sculpture – or at least for form as a contemplative object. From Berlinde De Bruyckere’s monumental fallen horses in Brussels to Tolia Astakhishvili’s demolished bathrooms in Venice, artists continue to explore materiality as a site of reflection and transformation. In Germany and Poland, however – nations that witnessed the early rise of the far right before its sweep westward – the most compelling exhibitions instead looked towards conflict in Ukraine and Palestine through research-driven practices and archival modes of presentation.

Berlinde De Bruyckere | Bozar, Brussels, Belgium

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s first large-scale survey in Brussels, ‘Khorós’, charts a quarter-century of her engagement with the uneasy threshold between the secular and the divine. Archangel III (San Giorgio) (2023–24), a barefoot, hooded figure on a wooden pedestal, set the scene for an exhibition that moved between devotion and unease. Throughout, De Bruyckere entwined violence, beauty, consolation and metamorphosis with characteristic intensity. Her monumental horse sculptures, slumped on tables (Lost V, 2021–22) or suspended mid-air (Lost I, 2006), carried a sacrificial charge. This concern with corporeality extended to gentler, more domestic, wall-hung pieces such as Courtyard Tales V (2018). Constructed from tattered blankets, the layered fabrics showcased the humble, tireless repetition – whether of a motif or conceptual idea – that underpins her practice. As Chloe Stead observed in frieze, ‘What prevents these works […] from tipping into sentimentality is De Bruyckere’s sincerity, which demands that the viewer respond in kind.’

Tolia Astakhishvili | Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, Venice, Italy

Touted by many at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale as the season’s standout off-site exhibition, Tolia Astakhishvili’s solo ‘to love and devour’ unfolded with a quiet, reverential charge. Developed during a four-month residency at Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation’s Dorsoduro 2829 – a 15th-century palazzo – the show treated architecture as a living archive. Here, the artist methodically striped the building to its bones: excavating walls, revealing plumbing, unearthing wire and boiler systems. In my emptiness (all works 2025), a demolished bathroom is reappraised as sculptural debris, hovering between ruin and repair. Moments of theatricality surface in I love seeing myself through the eyes of others, which sealed viewers out of a lit glass room, its opacity offering only fleeting hints of activity. Sean Burns described the project as ‘archaeological work with a speculative fiction slant, where gestures of deconstruction, subtraction and addition lead to a sense of learning’. The palazzo becomes a Gesamtkunstwerk, intimate yet uncanny, operating outside the confines of time.

‘Radical Software’ | Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria

This February, a mammoth group show, ‘Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991’, reopened the digital-art archive with a sharp feminist corrective. Gathering over a hundred works by 50 women artists – spanning drawing, sculpture, performance, film and algorithmic text – the survey reorientated media history around those long written out of it. From Hanne Darboven’s sprawling, handwritten code in Ein Jahrhundert ABC (A Century ABC, 1970–71) to Alison Knowles’s dot-matrix printer producing generative verse (The House of Dust, 1967), the exhibition proposed early computing not as sterile machinery but as an instantly human and tactile field. As Kathrin Heinrich noted in frieze: ‘Radical Software’ does some much-needed educational heavy-lifting’, reasserting women’s formative role in shaping the computational imaginaries that define the present.

David Hockney | Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France

What consistently draws me back to David Hockney’s work is his expert ability to lure you into his distinctive, beautiful worlds. Whether wandering the verdant fields of A Gap in the Hedgerow (2004) or drifting through the cerulean waters of Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972), the scenes from his prolific body of work are so familiar they almost read as memory. Tracing the last 25 years of his practice, ‘Hockney 25’ unfurled across the spacious galleries of Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Monumental opera-set projections from Hockney Paints the Stage (2025) bathed the gallery in theatricality, while the iPad landscapes of the ‘220 for 2020’ (2020) series appeared in slick, aluminium-mounted frames, affirming digital drawing as Hockney’s latest formal frontier. ‘This is a space of jouissance, not turmoil; of experimentation, not pontification; of acceptance, not resistance’, Sean Burns observed. Hockney’s largest exhibition to date felt less like a survey than a manifesto: a life-affirming ode to colour, light and the pleasures of looking.

Zahra Malkani | Konsthall C, Stockholm, Sweden

In a year filled with strong, sonically driven exhibitions – from Tarek Atoui’s music pedagogy to Tavares Strachan’s ode to Black recording artists – Zahra Malkani’s first European solo, ‘Sada Sada’, cut through with a sparse, incisive chorale on ecological activism as ritual. The eponymous eight-channel sound installation drew on footage and field recordings from Sindh, Pakistan, where Malkani traces the political tensions surrounding a river system strained by floods and extractive capitalist expansion. Chants in Balochi drifted in from Gadani beach, home to the world’s third-largest ship-breaking yard, folding industrial ruin into the work’s devotional, tidal register. The voices of women activists braided into the rush of seasonal waters, producing an insurgent, devotional rhythm. ‘For Malkani’ Matthew Rana noted, ‘the sacred is political and resonates with the ways in which protest is inscribed within acts of veneration and prayer.’ Through its magnetic score, Sada Sada cautions against ecocidal futures while insisting on histories of resistance that continue to reverberate within and around us.

‘11 Parthenon’ | 11 Parthenon Street, Nicosia, Cyprus

The most intimate exhibition on this list is ‘11 Parthenon’, a group show staged in the residence of Andre Zivanari, director of Point Centre for Contemporary Art. As Ben Livne Weitzman wrote, the show excels in its reimagining of the domestic, turning the home into ‘a site of accumulation – of emotions and quotidian histories – a space for gentle interruptions and understated transformations.’ Artists tilted the familiar – mundane objects, routines, private memories – into forms both tender and strange. On the kitchen counter, Iris Touliatou’s Analogue (cheese platter) (2025) stacked cheese slices as a sociological still life of Cyprus’s class stratification. In the basement, Stelios Kallinikou’s black and white short film, Two minutes twenty two seconds thirty two milliseconds (2024), observed a clockmaker at work. Evoking fragile monumentality, a pile of white feathers heaped in a hallway corner formed Petrit Halilaj’s Untitled (For Felix) (2020), an homage to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s ‘Candy Works’ (1990–1993). The unpretentious, vulnerable way in which we encountered these works is a testament to what becomes possible when intimacy becomes an exhibition form.

Lutz Bacher | Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, Norway

Themes of absence, erasure and remembrance hover throughout Lutz Bacher’s first posthumous museum retrospective, ‘Burning the Days’. Mapping five decades of her radical practice, the show eschews a linear path, unfolding instead through ‘associative encounters’ – a curatorial structure that mirrors Bacher’s own fluid, open-ended methodology. Questions of legacy and loss surface in Closed Circuit (1997–2000), a surveillance-based film documenting Pat Hearn – Bacher’s art dealer and downtown New York linchpin – captured at her desk in the years before her death in 2000. Elsewhere, Bacher extends this inquiry into the wider terrain of American mass culture: Disney film canisters from Snow White (2009), gun-magazine advertisements from FIREARMS (2019) and other scavenged objects appear as charged cultural residues. As Jonathan Odden warns, ‘Plenty will make the viewer pause and leave them uncomfortable. Still, Bacher knew the best questions were the ones that bugged you most.’ ‘Burning the Days’ runs until 4 January 2026.

Medardo Rosso | Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland

This summer, I was taken aback by 19th-century Italian artist Medardo Rosso’s ‘Inventing Modern Sculpture’ – a bracing reminder of sculpture’s capacity to remain elastic and perpetually in flux. The retrospective brought together around 50 of Rosso’s wax, plaster and bronze figures in dialogue with contemporary artists. Rosso’s Aetas aurea (1886), a mother and infant locked in suffocating embrace, echoed uncannily in the entwined limbs of Louise Bourgeois’s Child devoured by kisses (1999). His works rejects the monumental in favour of ephemerality; the faces in his crudely-hewn busts often appear half-formed, as if struggling to extricate themselves from the very substrate that birthed them. This mutability reverberated through the contemporary works on view, from Alina Szapocznikow’s octopus-like gum formations in ‘Fororzeźby’ [Photosculptures] (1971/2007), to the slumped, silken folds cascading over the figure in Andra Ursuța’s lead crystal work, Grande Odalisque (2022).

Kyiv Biennial | MoMA Warsaw, Poland

The sixth edition of the Kyiv Biennial, ‘Near East, Far West’, foregrounds colonial violence, erasure and genocide. Framed through the curators’s notion of ‘Middle East-Europe’ – spanning Central and Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Central Asia and the Middle East – the exhibition feels acutely charged amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s devastation of Gaza. Artists distancing themselves from Western European tropes, instead deploy strategies of counter-mapping and embodied documentation. Lana Čmajčanin’s 551.35 – Geometry of Time (2014) glows with layered cartographies charting 551 years of shifting Bosnian borders, while in Nikita Kadan’s Silence in the Classroom (2025) rows of school desks hold open books on Ukrainian art history, encircled by pedestals topped with twisted metal sculptures cast from wartime rubble, turning the debris of Russian aggression into a fortification of cultural memory. For many of the artists, war remains a defining context, something the biennial thankfully does not let us forget. ‘Near East, Far West’ runs until 18 January 2026.

‘Unsettled Earth’ | Spore Initiative, Berlin, Germany

‘Unsettled Earth’, a tender and defiant group exhibition at Berlin’s Spore Initiative, reframed Palestinian histories through agrarian and ecological lenses, working closely with artists whose practices centre land defence, communal autonomy and environmental repair. In Until we became fire and fire us (2023), Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme spliced footage of sonic rituals from Iraq, Palestine, Syria and Yemen with studies of indigenous plants and poetic fragments, producing an unsettling rhythm; while Bayan Abu Nahla’s Airdrops (2024), rendered in soft watercolour, depicted Gazans sprinting across a beach towards an aid parcel drifting in shallow water. What becomes of land once its population has been devastated and exploited? And how might it be reclaimed? These questions reverberate with particular force in Germany, a country still wrestling with its Nazi past while right-wing narratives advance into mainstream politics. Against this backdrop of cultural anxiety and tightening censorship, Spore Initiative’s yearlong programme argued that research-driven art institutions can have long-term impact.

Main image: Tolia Astakhishvili, I love seeing myself through the eyes of others, 2025, acrylic paint, photos, found objects, material storage, light, 614 × 430 × 290 cm. Sound by Dylan Peirceplastic. Courtesy: the artist