‘Broken Columns’ Finds Beauty in Institutional Critique

The Museum of Mexico City group exhibition highlights artists using aesthetics to hold their governments accountable

The Museum of Mexico City group exhibition highlights artists using aesthetics to hold their governments accountable

Intermittently defunct for the past 12 years, the Museum of Mexico City has been rented and renovated by curator Francisco Berzunza to host his exhibition ‘Broken Columns’ (2025–26), featuring 62 international artists around the loose theme of rejection. Berzunza intentionally produced the exhibition without state funding, enabling him to include works critical of the Mexican government, such as its historic repression – or rejection – of Indigenous artists like Máximo Pacheco. As an artist of Otomi heritage, Pacheco worked as a mural assistant to Diego Rivera for his monumental paintings for the Mexican Revolution in the Ministry of Education (1922–24). Pacheco went on to paint several murals of his own in schools, but over the years they were destroyed during building demolitions. Some of the only remaining photographs of Pacheco’s murals are by Tina Modotti, on display in the exhibition, restoring his forgotten legacy.

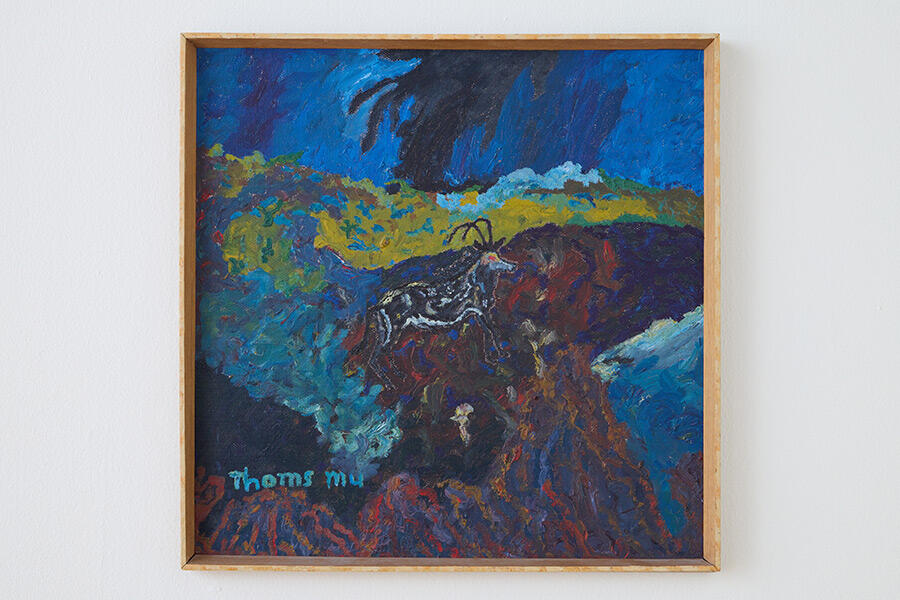

There is a revisionist instinct to ‘Broken Columns’, which features artists who were rejected by the received art historical canon. A suite of impressionistic, mythological paintings by the Indigenous Sohna artist Thomas Mukarobgwa, such as Sable Going Around (1962), reverse years of neglect by Western art institutions. Other works present people rejected by Mexican society. Daniela Rossell’s ‘So, Why Do You Complain?’ (2008–25) features unfinished paintings of mentally ill and disabled people who were photographed for the tabloid TV Notas as a freak show feature (the photos were conspicuously erased from the magazine’s official archive). These works arrive following a 20-year hiatus after her ‘Rich and Famous’ (2002) photo series of the Mexican aristocracy provoked public outcry – in a country where 54% of the population had been living in poverty.

Ramon Saturnino’s don’t speak; don’t talk (2025) is a more contemporary rejection of Mexican politics. It is composed of black, abstract structures modelled after police barricades, while its tall rectangular frames recall the border wall that Saturnino saw erected in his hometown of San Luis del Rio Colorado in Sonora at the US-Mexico border. The sculpture was conceptualized as an outdoor, site-specific installation, where police barricades were erected to block protesters camping in the Zócalo after the government failed to prevent the assassination of leftist mayor Carlos Alberto Manzo Rodríguez. When the local government banned Saturnino’s sculpture from being exhibited in the square, it was relocated to inside the museum, where the work took on a largely apolitical, minimalist idiom. Here, a tension between institutional critique and ‘art for art’s sake’ is problematized. As it is now displayed, don’t speak; don’t talk explores formal relations of the modernist grid to the viewing body, relations that feel largely irrelevant to the context from which it was forcibly alienated.

What is the role of beauty in institutional critique? ‘Broken Columns’ seems suspicious of beauty, positioning it as ancillary to liberation. Yet some works resonate more subtly on an aesthetic level rather than in their explicit political commentary. Beatrice Olmedo’s Pneuma (2025), cast from prosthetic limbs and synthetic organs, is intended as a critique of the Mexican healthcare system, defunded by austerity measures, yet the hanging sculpture of gleaming, translucent orthotic plastic is grotesquely alluring: the viewer subconsciously recognizes themselves when their own form is reflected back as alien. It is indexically formatted to the human body – the prosthetics are moulded from the sockets of amputees – yet it appears simultaneously abstract. Attached to a motor, the sculpture – partly made from breast implant material – periodically inflates, mimicking human breath. Here, we respond to the ancient pleasure of mimesis, even when confronting the body at its most deformed and discombobulated (which can stand for the broken civic body, if you want it to).

‘Broken Columns’ succeeds as a strong voice against sociopolitical and cultural rejection or neglect, at a time when virtually all city museum exhibitions are showing ‘beautiful’, abstract and apolitical art. But despite itself, the art of critique can be beautiful, too – a quality the show presents as worth protecting.

‘Broken Columns’ is on view at the Museum of Mexico City until 8 March 2026

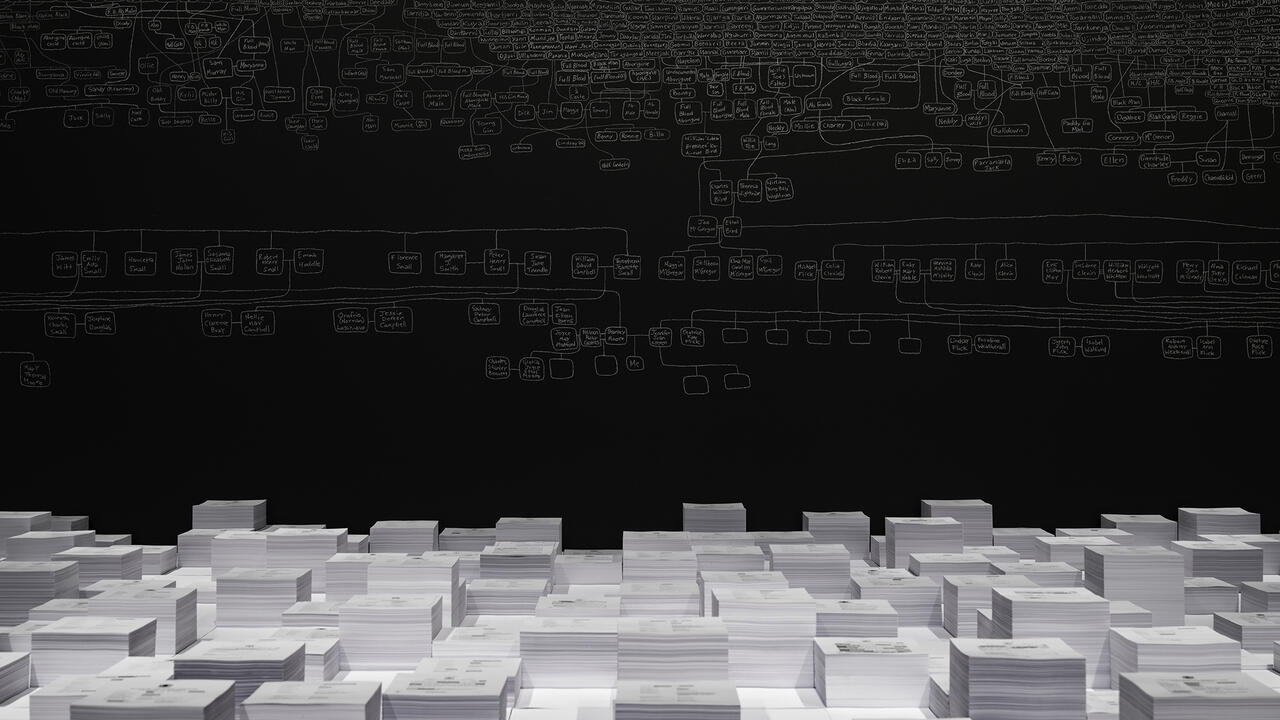

Main image: Daniela Rossell, ‘So, Why Do You Complain?’, 2008–25, installation view. Courtesy: Museum of Mexico City; photograph: Tom de Peyret