‘Deviant Ornaments’ Unearths Queer Lineages Within Islamic Art

At Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, a thoughtful pairing of historical artefacts and contemporary works reveals how faith, cultural belonging and queer identity intersect in unexpected ways

At Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, a thoughtful pairing of historical artefacts and contemporary works reveals how faith, cultural belonging and queer identity intersect in unexpected ways

‘Deviant Ornaments’ at Nasjonalmuseet argues that expressions of same-sex desire can be found throughout the history of Islamic art – if only one knows where to look. A small but striking selection of sensuous, richly decorated artefacts demonstrate strands of desire encoded throughout centuries of courtly ritual and décor, while pieces by contemporary artists, working within a queer and Muslim context, offer a charged contrast between historical opacity and present-day transparency.

A drawing with delicate, flowing linework, attributed to Muhammed Qasim and dated around 1650, depicts a Safavid prince holding court, surrounded by functionaries and musicians. The male attendants dotted throughout the scene are all young and beardless, a recognized trope holding erotic connotations in Persian poetry and painting. Other objects within the exhibition are less straightforward to read. For instance, a long men’s coat made in Iran between 1900 and 1930, densely patterned with florals, indexes the friction between European ideas of ornamentation as inherently feminine and Persian traditions in which it signified high social status.

Among the jewellery and decorative items, a fragment from an 11th-century Fatimid lusterware plate shows a man drinking wine with a male musician beneath a tree, framed by flowing Arabic calligraphy. That expressions of same-sex attraction are often indirect – and in many cases debatable – is interesting and unconventionally open-ended for a museum exhibition. It also serves as a reminder that current categories of sexuality are by no means universal. Archival absences around queer lives in Islamic contexts may reflect not only persecution and suppression but also practices and identity markers that diverge radically from contemporary LGBTQ+ discourse.

Many of the contemporary works reimagine the art and culture of the past. Kasra Jalilipour’s ‘Queer Alterations’ series (2022–24) digitally edits illustrations from a historical Persian erotic manual to depict queer, trans and lesbian figures, presenting sex as a spiritual or transcendent act. Rah Eleh’s 3D-printed sculpture, Amorous Couple (2025), derives from a 17th-century Mughal sketch and features two female figures sitting face to face, one aiming a dildo-tipped arrow at her partner’s crotch. The exhibition’s wall text claims it as one of the few depictions of lesbians in Islamic art history, but leaves out the work’s obvious debt to Hindu art and its more permissive erotic conventions. The Mughals were Muslim, but they ruled a Hindu-majority population, and their court workshops drew on both Persian and Hindu artistic traditions.

Fake World (2011) by Taner Ceylan is a kitschy, photorealistic oil painting depicting a nude young man draped in gold fabric, Arabic script tattooed across his neck. The soft, glazed look of his skin and his generic, gym-toned good looks evoke softcore pornography or reality TV. The work feels misplaced in an exhibition that otherwise asks viewers to read queerness through ornament, coding, ritual and cultural friction.

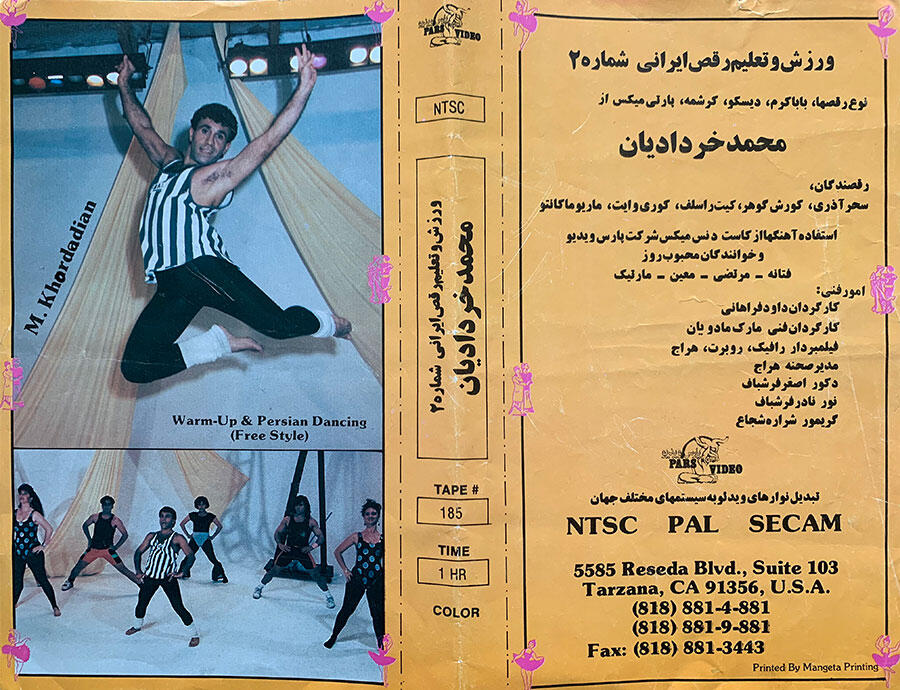

Far more resonant is Dance after the Revolution, from Tehran to L.A., and Back (2020), a video by Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian. It traces the viral, pre-internet dance videos of exiled Iranian choreographer Mohammad Khordadian, whose instructional tapes – smuggled back into Iran on VHS – had a significant influence on dancing at weddings and parties, licensing more expressive, fluid styles that had previously been considered too feminine for men. A clear strain of camp runs through these entertaining clips, reminiscent of voguing and other dance styles that challenge the gender binary.

‘Deviant Ornaments’ may not offer an encyclopaedic queer history of the Islamic world, and its historical context is sometimes left thin. Its strength instead lies in its visual density, its abundance of pleasures enveloped in rich décor and intricate pattern and in the friction it stages between coding and disclosure, past and present. Here, faith, cultural belonging and queer life emerge not as contradictions but as intertwined in complex and often surprising ways.

‘Deviant Ornaments’ is on view at Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, until 15 March 2026

Main image: Damien Ajavon, Chemin vers Oslo (detail), 2025. Courtesy: © Damien Ajavon / BONO; photograph: Annar Bjørgli / The National Museum