Bridget Riley Makes Art Out of Reiteration

A survey of her paintings at Turner Contemporary, Margate, shows the consistency of her vision but reveals nothing new about the nonagenarian artist

A survey of her paintings at Turner Contemporary, Margate, shows the consistency of her vision but reveals nothing new about the nonagenarian artist

‘Learn to draw well and appreciate the sea, light, the blue sky.’ This was the advice given to a teenage Claude Monet by the painter Eugène Boudin. The injunction to embrace nature – learning from the visible world rather than academic theories – proved decisive. Forty years later, Monet would write to his mentor: ‘I haven’t forgotten that you were the first to teach me to see and understand.’

It was Monet’s statement in this letter that inspired the title of Bridget Riley’s exhibition, ‘Learning to See’, a condensed display of 26 paintings and drawings dating from the 1960s to the present day. Smaller than a retrospective, but with the same breadth of timeframe, it is a bold, uncomplicated testament to the consistency of her vision. Like Monet, an artist whom she regards as a touchstone, Riley has continued to articulate the double process of seeing and understanding – aligning technical precision with an affinity for colour, light and space.

In the foyer preceding the first gallery, a fragment of a wall painting – Bolt of Colour (Wall Painting) [Marfa] (2017) – has been reproduced across the corner of the room, directly opposite a picture window that looks out to sea. The mural consists of horizontal striations of varying widths, a mid-turquoise emerging – after a few seconds of viewing – as the dominant shade. At the centre, a thick band of white traverses the composition. Its upper edge aligns precisely with the real-life horizon visible through the window. A study in chromatic collision and hard-edged line, the mural is also, in the most elemental sense, a panoramic view: a glimpse of Marfa juxtaposed with the coast of Margate.

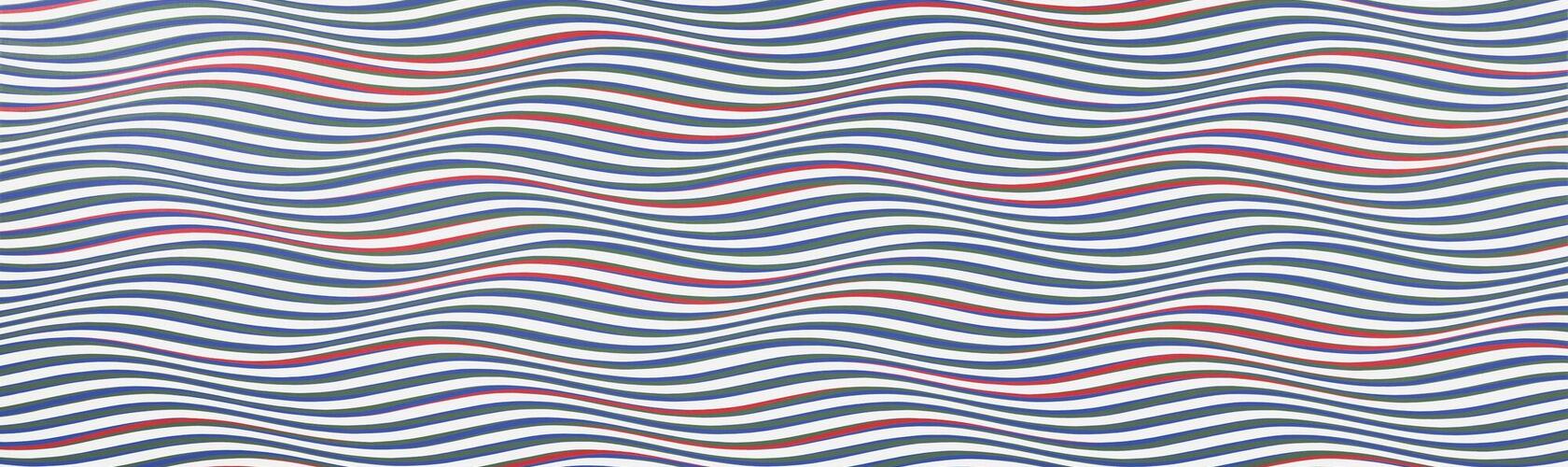

The non-chronological arrangement of the exhibition helps to show how this schematization of the visible world has formed a constant throughout Riley’s career. The earliest painting in the display, Arrest 3 (1965), which appears in the first room, comprises a stack of wave formations in shades of black and grey. It is a classic work of Op art – the sleek undulations seeming to wobble before the eye. Oscillating between illusionism and flatness, the painting distils the fundamentals of image making. At another level, it evokes the mid-bending distortions of fairground mirrors. In Riley’s work, geometric strictness doesn’t preclude a sense of the wayward or even the irrational.

Many of Riley’s paintings produce a similar destabilizing effect – their waves, lines or repeating deltas inducing a momentary dizziness. At times, it is impossible to construe an image. Winter Palace (1981) is one of a long sequence of works composed out of multiple narrow vertical lines – their colours varying and repeating with an inscrutable logic. The illusion of depth has all but disappeared. The bands of colour are what they are, and nothing more – the picture might be regarded an epitome of post-painterly abstraction. And yet the title of the work, which refers to a trip to the Egyptian city of Luxor (specifically, the Winter Palace hotel, where Riley stayed) insists on a real-life point of reference. The colours are those of actual experiences – of a given time and place.

Not only does Winter Palace allude – in an oblique, coded form – to an event in the artist’s life, but it constitutes its own internal sequence of occurrences. Riley has referred to the stripes, with their chromatic jolts and refrains, as ‘visual events’. All of her paintings might be regarded in this way, although, in the unstructured display at Turner Contemporary, they have the appearance of all belonging to the same moment. Walking through the galleries without consulting the labels, it is easy to imagine that a work from the 1980s was made in the last decade, or vice versa. Her art refers constantly to its own earlier iterations. Silvered Painting 2, which closely approximates Winter Palace, is bafflingly dated 2023–1981, as though the creation of the picture were an act of going back in time rather than one of moving forward. Time, as much as space, is elastic – collapsible – in Riley’s art.

The final gallery is dominated by Dancing to the Music of Time (2022), a mural of 29 platter-sized circles in earthen shades of green, brown and purple, scaling the wall like giant points on a scatter graph. There is a semblance of weightlessness to the coloured orbs, and yet the underlying grid asserts its presence. There is, ultimately, a strict conformity about Riley’s structures. They never subvert their own logic. This is their strength, as well as their fundamental limitation: her compositions are forever subservient to their own rules.

Lacking the constraints – the angle or argument – of a curated retrospective, ‘Learning to See’ sets Riley’s works in free play, as though the paintings themselves are the disparate motifs of a larger pattern. What that pattern reveals is hard to say. Walking through this elegant, succinct show, one can’t help wondering what it tells us about Bridget Riley that we don’t already know. But then, as her work so often implies, revelation may be beside the point. Just as there is nothing new in nature, she has made an art out of reiteration.

Bridget Riley’s, ‘Learning to See’, is on view at Turner Contemporary, Margate, until 4 May 2026

Main image: Bridget Riley, Streak 3, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 1.1 × 2.5 m. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: John Webb © Bridget Riley 2025