Remembering Paula Rego’s (1935–2022) Bruising Visions of Womanhood

Rosanna McLaughlin explores how the late feminist artist redressed politics and power in her semi-autobiographical paintings

Rosanna McLaughlin explores how the late feminist artist redressed politics and power in her semi-autobiographical paintings

In the BBC documentary Paula Rego: Secrets & Stories (2017), the artist describes painting as a place where you can ‘let all your rage out’. Rego, who died aged 87 on 8 June 2022, leaves behind a body of work shaped by a powerful drive to exorcise the bruising experiences of womanhood and to make stories from the torments, desires and mischiefs of the heart.

Born in Lisbon in 1935, during the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar, Rego described, in the documentary, the Portugal of her youth as a place where men would meet for lunch and then ‘go to the whorehouse to fuck’, and the best a woman could hope for was a life of idleness. In 1951, at the behest of her parents, who believed there were few opportunities for women under Portugal’s repressive regime, Rego moved to the UK, initially attending finishing school in Kent before dropping out and enrolling at the Slade School of Fine Art in London.

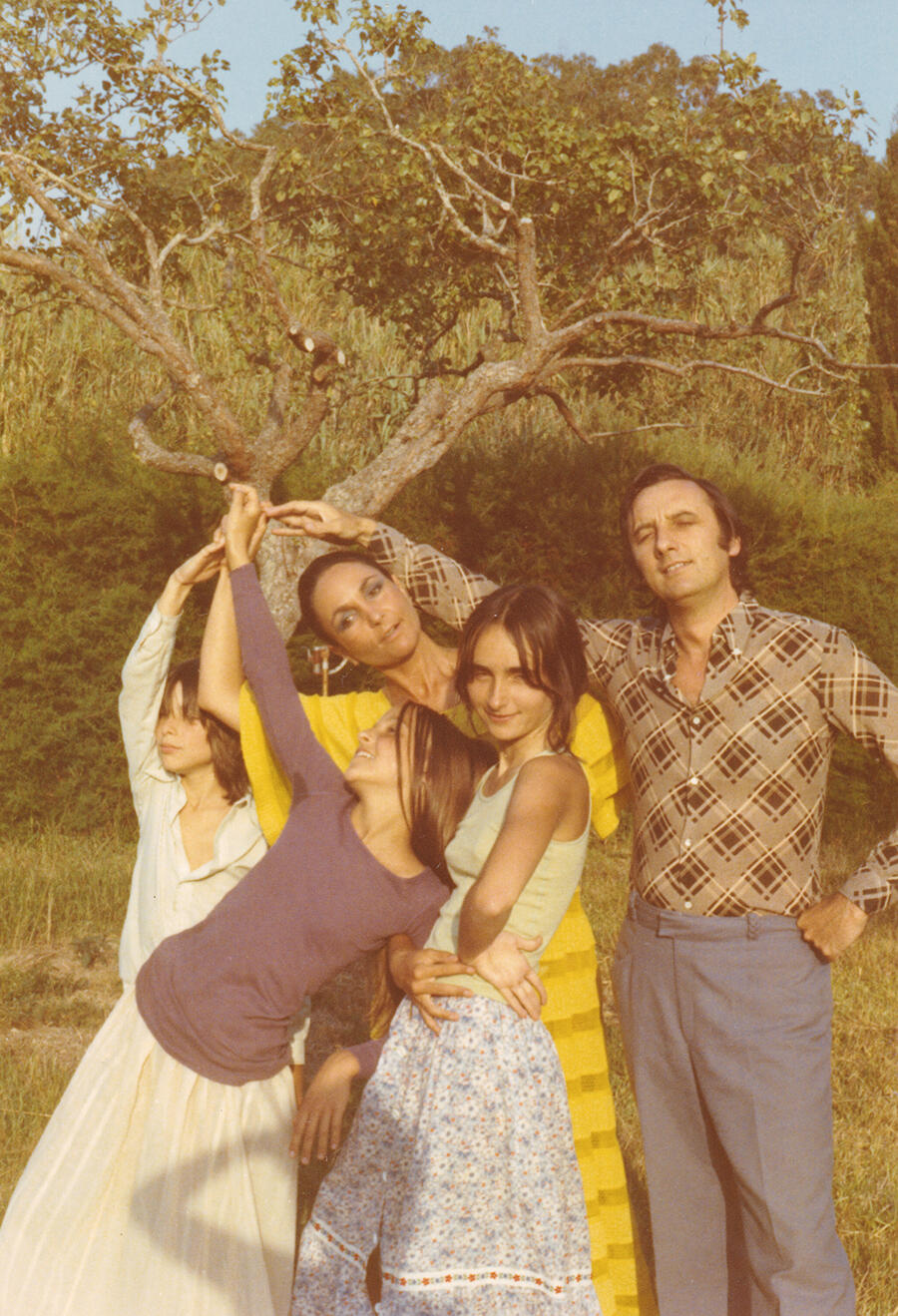

There, she met the painter Victor Willing, with whom she eventually had three children and shared a turbulent marriage. Following Willing’s death in 1988, two decades after he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, her children recalled her screaming: ‘Who’s going to help me with my work now?’ Only when reminded of this outburst in Paula Rego: Secrets & Stories does she chide herself for such a remark. Rego was, by her own admission, married to painting – a vocation that came before everything else.

Like other female artists of her generation, Rego found herself buffeted by opposing forces: the expectation to prioritize her role as mother and wife; the erotic appetite she felt duty-bound to suppress; and her ferocious artistic ambition. Rego channelled the conflicts she faced into her art, creating intense paintings that combine social commentary, mythology and autobiography.

Stray Dogs (The Dogs of Barcelona) (1965), an exuberant and unsettling work, was produced in response to a disastrous initiative to poison the Spanish city’s feral dogs with tainted meat that ended up killing unsuspecting homeless children who ate it out of desperation. At the top of the composition is a lascivious face with a protruding tongue, added after Rego discovered her husband kissing another woman during its production.

In 1973, during a period of economic hardship and poor mental health, Rego began Jungian analysis and became fascinated with the ways in which folklore enabled her to access the hidden sources of her emotions. This interest inspired the narrative-driven works for which she is best known: serrated and subversive fairy-tale visions in which she appears to look death, danger and the patriarchy in the eye, and wink. In The Policeman’s Daughter (1987), for instance, a girl in a white dress has shoved her arm deep inside the black leather men's boot that she is polishing; The Family, made the following year, draws on Willing’s deteriorating health and depicts a troubling bedroom scene in which children attempt to dress and revive a frail man. Both paintings, as with much of Rego’s work, allude to the fraught power dynamics between men and women.

Rego, who was open about her experiences of backstreet abortions and felt strongly that abortion should be legalized, considered her best work to be the ‘Abortion Series’ (1998–99): ten large, brutally matter-of-fact paintings in which women squat over buckets or sit with their legs raised on the backs of chairs used as makeshift stirrups. She created the series after the turnout for the 1998 referendum on abortion in Portugal was so low that it failed to reach the legal threshold. The series has since been credited with turning the tide of public opinion in favour of full decriminalization – a bill that was eventually passed in 2007.

From 1985 onwards, Rego worked with the model Lila Nunes, who had been Willing’s carer and appears in many of the Portuguese artist’s most celebrated works. As her career matured, Rego began to incorporate garish handmade puppet models, which give the figures in her paintings a dreamlike and disorienting relationship to scale.

In a 2021 interview with Kate Kellaway for the Guardian, Rego described her routine during the COVID-19 pandemic as follows: driving by taxi to the studio with Nunes, listening to opera, reading stories, painting and finishing the day with champagne. By the time she died, Rego had become a household name, embraced by the highest orders in both the Portuguese and British establishments. In 2002, she was invited by the then-president of Portugal, Jorge Sampaio, to create a series of paintings on the life of the Virgin Mary for Belém Palace, the official residence of the Portuguese head of state; in 2009, the Casa das Histórias (House of Stories), a museum in the seaside town of Cascais near Lisbon, was built in her honour; the following year, she was made a dame of the British Empire.

Throughout her life, art remained a constant outlet, a way of giving form to the psychological currents that swirled beneath the surface. ‘It’s terribly important to have a story’, she told her son, Nick Willing, while filming Paula Rego: Secrets & Stories. Long may hers be remembered.

Main image: Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1994, pastel on canvas, 120 × 160 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro