Som Supaparinya Exposes How Power Manifests Through Censorship

At the Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, the artist weaves archival materials into a video installation exploring the Cold War’s imprint on Thailand

At the Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, the artist weaves archival materials into a video installation exploring the Cold War’s imprint on Thailand

In her research-based practice, artist Som Supaparinya combines visually layered video works with photography, tangible objects and storytelling to disrupt the process of historical amnesia and reveal the rhizomatic webs of critical moments that embroil communities and nations. Supaparinya’s solo exhibition ‘MO NUM EN TS’ showcases a video installation of the same name that examines the legacy of the Cold War in Thailand through materials produced by the United States Information Service (USIS). Propagandist in nature, the archival materials exalt Thailand’s rapid development during the 1960s and ’70s while foregrounding the country’s bilateral alliance with the US. Creating an audiovisual realm where archival materials interweave with landscapes and national infrastructures, Supaparinya invites viewers to reflect on how Cold War ideologies continue to shape collective perception and knowledge in Thailand under the guise of progress and development.

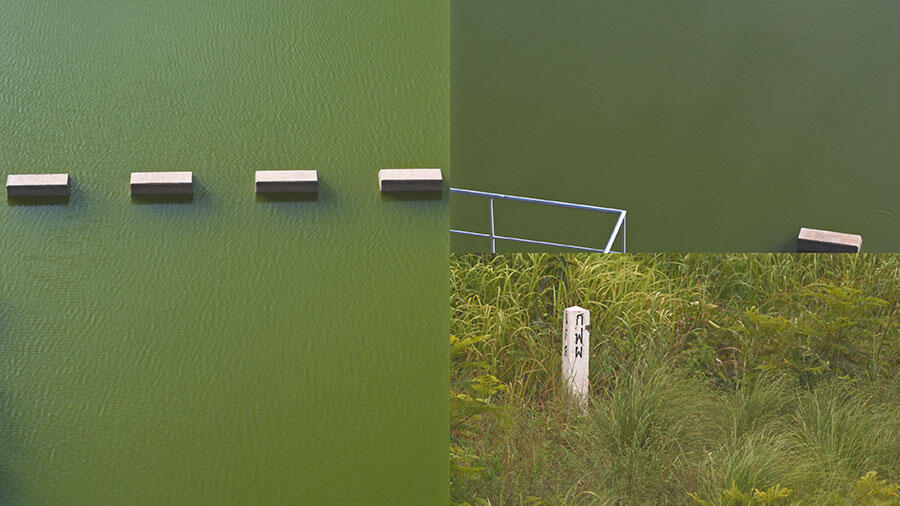

The space where MO NUM EN TS (2025) is installed resembles a military base’s command centre: the large screen mimics the grid of a CCTV monitor, while a wall is built out to evoke the sluice gates found in hydroelectric dams. The effect is one of control, intensified by the video’s alternation between bird’s-eye views and wide shots of landscapes. Familiar from their use in military surveillance – and clearly visible in the topographic maps and aerial photographs of Cold War infrastructure, such as US Air Force bases and highways across Isan (Northeast Thailand), that Supaparinya extracted from both Thai and US archives and intersperses throughout the work – these camera angles conceal the desire to monitor beneath the pretence of objectivity.

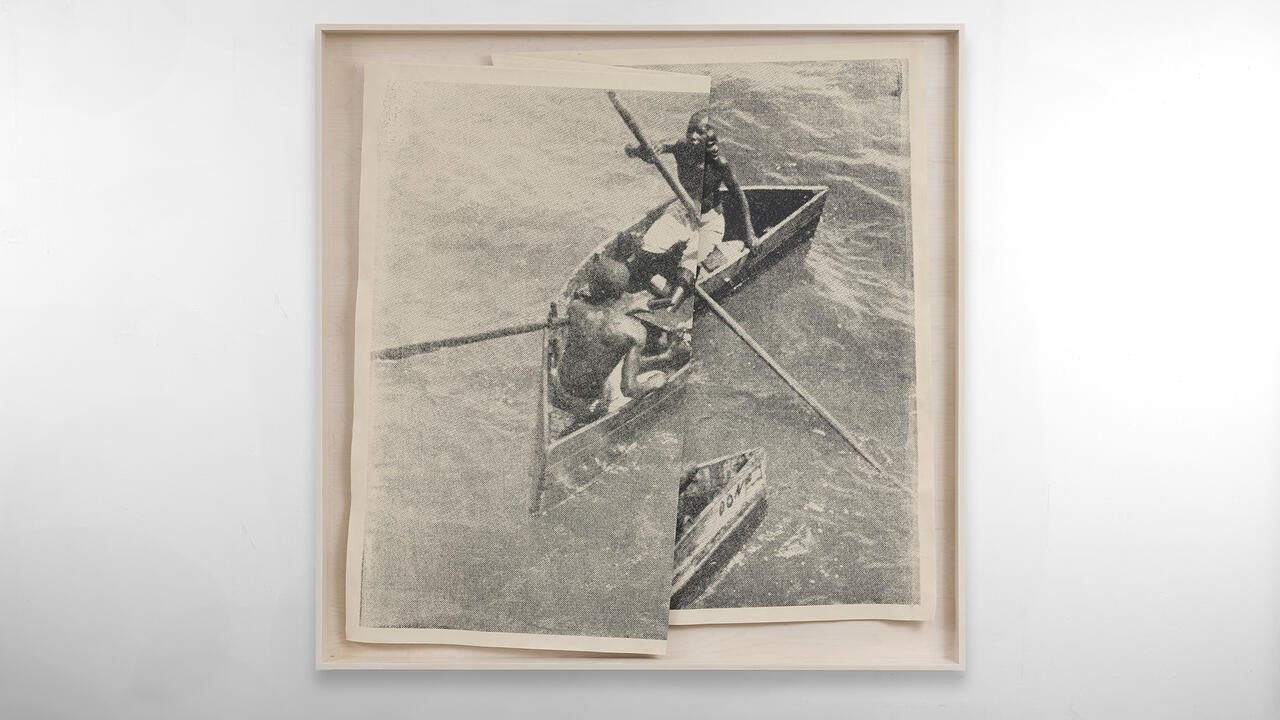

At first glance, Supaparinya’s video installation might give an impression of archive-validated celebration, even nationalist bravado. Yet her compositional decision to collage multiple views into a single screen fractures these archives’ historical certainty: while together the images form a seemingly seamless shot, subtle dividing lines point to the Cold War’s ideological ruptures. In a quotidian shot of Thai and Lao vendors engaged in their work at the rambunctious Thai–Lao market by the Mekong River in Nakhon Phanom, a single vertical line persistently separates the two people on screen – alluding to the countries’ tense Cold War relations, marked by border skirmishes and ideological conflict.

Throughout the video, and especially towards the end, Supaparinya quietly amplifies this simmering tension. A montage of hydroelectric dams across Thailand, many of them named after Thai monarchs, such as Sirindhorn or Bhumibol – a tactic devised by US construction companies to render the dams ‘sacred’ and therefore untouchable – is immediately followed by footage of civilian protests in 2003, decrying the ecological impact and human displacement caused by the Pak Mun Dam in Ubon Ratchathani. Of all the dams included in the work, Pak Mun is the only one without a royal title – achieved through a push by local communities to stake their claim against the imposed disruption of their environment.

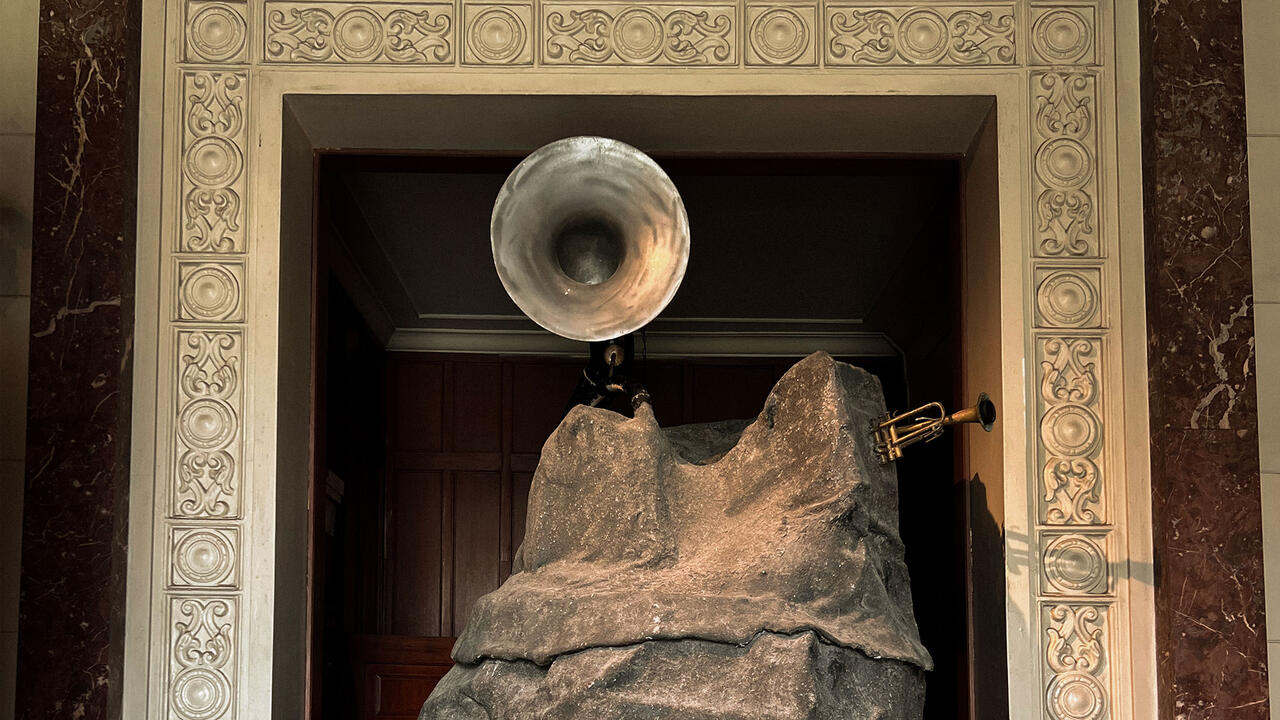

MO NUM EN TS ends on a cliffhanger, revealing neither the fate of the dam nor that of the people affected by it. Supaparinya’s sentiment nonetheless remains transparent: if archives can lie, if control is a state’s default, then our search for historical truths and autonomous existence cannot be divorced from the view of the people. This quest for freedom also figures into a version of the artists’ earlier installation Paradise of the Blind (2016/25), a pop-up library displaying books that have been banned across Asia, here displayed alongside an installation in which bullets rain down on piles of shredded paper from photocopies of said books. Exposing how power manifests through the censorship of knowledge, together Supaparinya’s two works create a space for audiences to contemplate the ways in which memory, knowledge production and the natural landscape intertwine.

Som Supaparinya’s ‘MO NUM EN TS’ is at Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, until 29 March

Main image: Som Supaparinya, MO NUM EN TS, 2025, film still. Courtesy: the artist and Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok