Beatrice Bonino’s Precious Trash

At Fondation Pernod Ricard, Paris, the artist’s sculptures grant everyday detritus improbable permanence as packaging and object converge with relic-like reverence

At Fondation Pernod Ricard, Paris, the artist’s sculptures grant everyday detritus improbable permanence as packaging and object converge with relic-like reverence

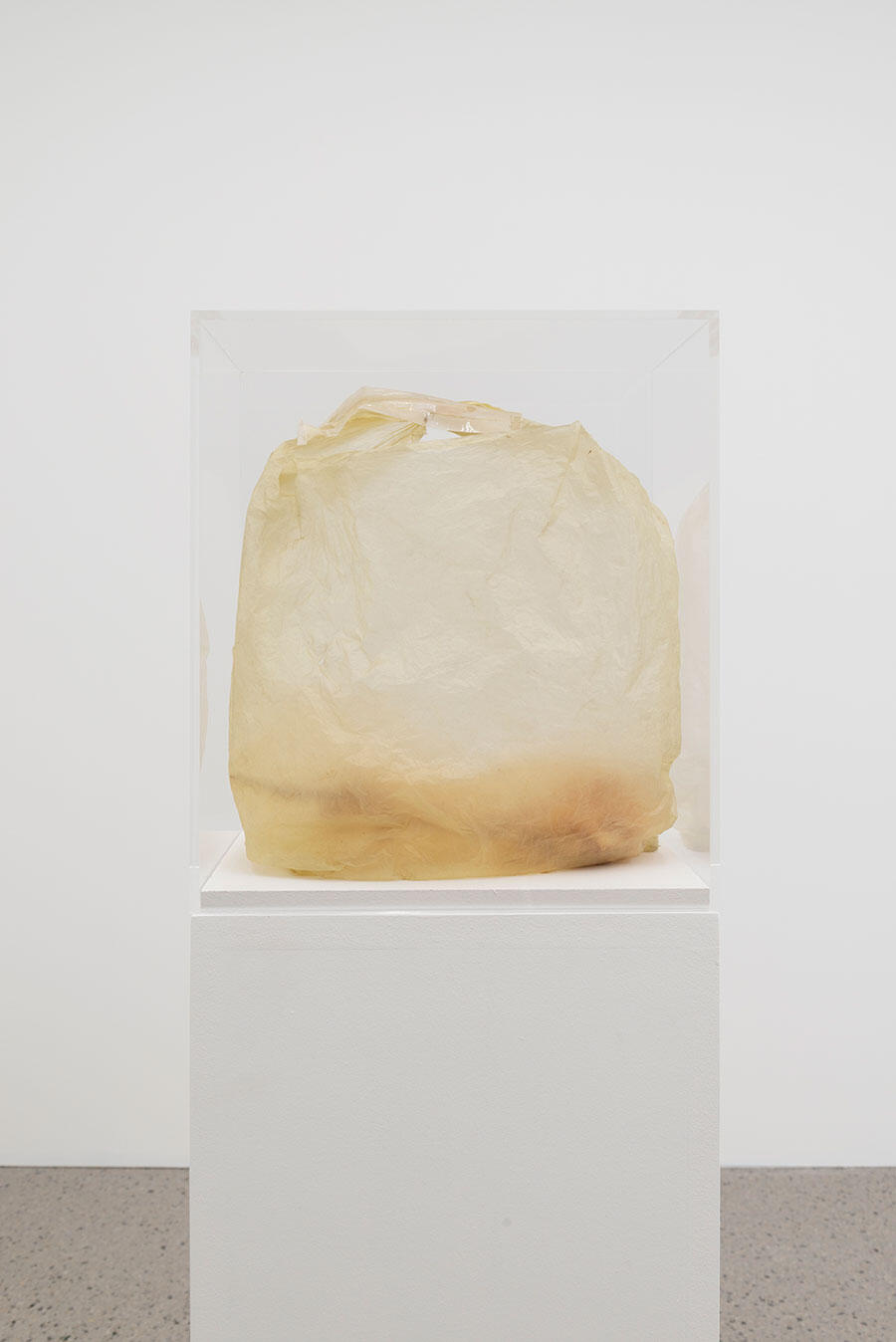

A perished rose, still clinging to the pink blush of its youth, rests at the bottom of a plastic bag, itself long past its prime. The work, The Carrier Bag (2025), appears in Beatrice Bonino’s solo exhibition, ‘In the main in the more’, which plays out across two white-cube rooms at the Fondation Pernod Ricard. Sculptures on pedestals, scattered sparsely across the gallery, share the same dusty, yellowed hues as their wall-mounted siblings.

The accompanying text describes the rose as coming from the Palaepaphos archaeological site in Cyprus, a detail emblematic of how Bonino approaches her materials as an archaeologist might, albeit one who attends to a different timeline. Her works preserve forgotten memories from the present day, resurrecting and isolating materials seemingly disposable in contemporary Western societies. The objects she employs – some teetering on the edge of disintegration – might seem frail if shown in isolation, but as part of Bonino’s precise assemblages they occupy an equilibrium somewhere between a recent birth and an impending demise.

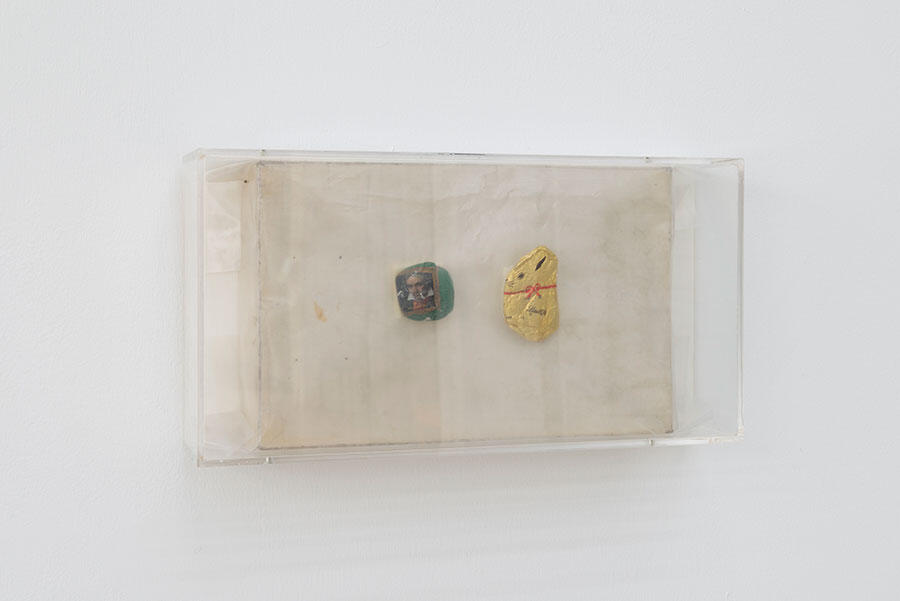

Bonino’s works frequently employ the materials of preservation – acrylic boxes, glassine paper – rendering uncertain the distinction between ‘contents’ and ‘packaging’, as well as alluding to a given object’s monetary or cultural value. In Funny and Fun (2024), for example, a squashed Lindt chocolate bunny is laid to rest alongside a similarly distorted foil-wrapped confection bearing the face of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The two chocolates, both signifiers of taste or quality, are unceremoniously pinned abreast with a nail through their centres – as a lepidopterist might mount a butterfly – and covered in a layer of plastic, then encased in a neat acrylic box.

I’m reminded of the work of Jef Geys, particularly his ‘Bubble Paintings’ (2017) – earlier pieces that were newly dated and re-exhibited inside the bubble wrap from the previous show or storage container. Like Geys, Bonino uses wrapping and layering to enliven her objects, bestowing the materials she describes in the accompanying text as ‘precious trash’ with a value that feels intrinsic. We might now peer through the display case, willing the bunny’s golden wrapper to be 24-carat, or Beethoven’s image to be a period-correct, hand-painted miniature.

Bonino’s reverence for the residues of modern life might be seen as a critique of the capitalist mass production that fosters throwaway culture. We may arrive at such an argument, but the path is indirect: we are first invited to confront our own fragilities through the sombre beauty of a length of paper, browned and curled at its edges (But Should Something Else Be Made Sacred, 2025), or a scrap of blemished ribbon (Which Is Ennui?, 2025), no longer the embellishment it once was.

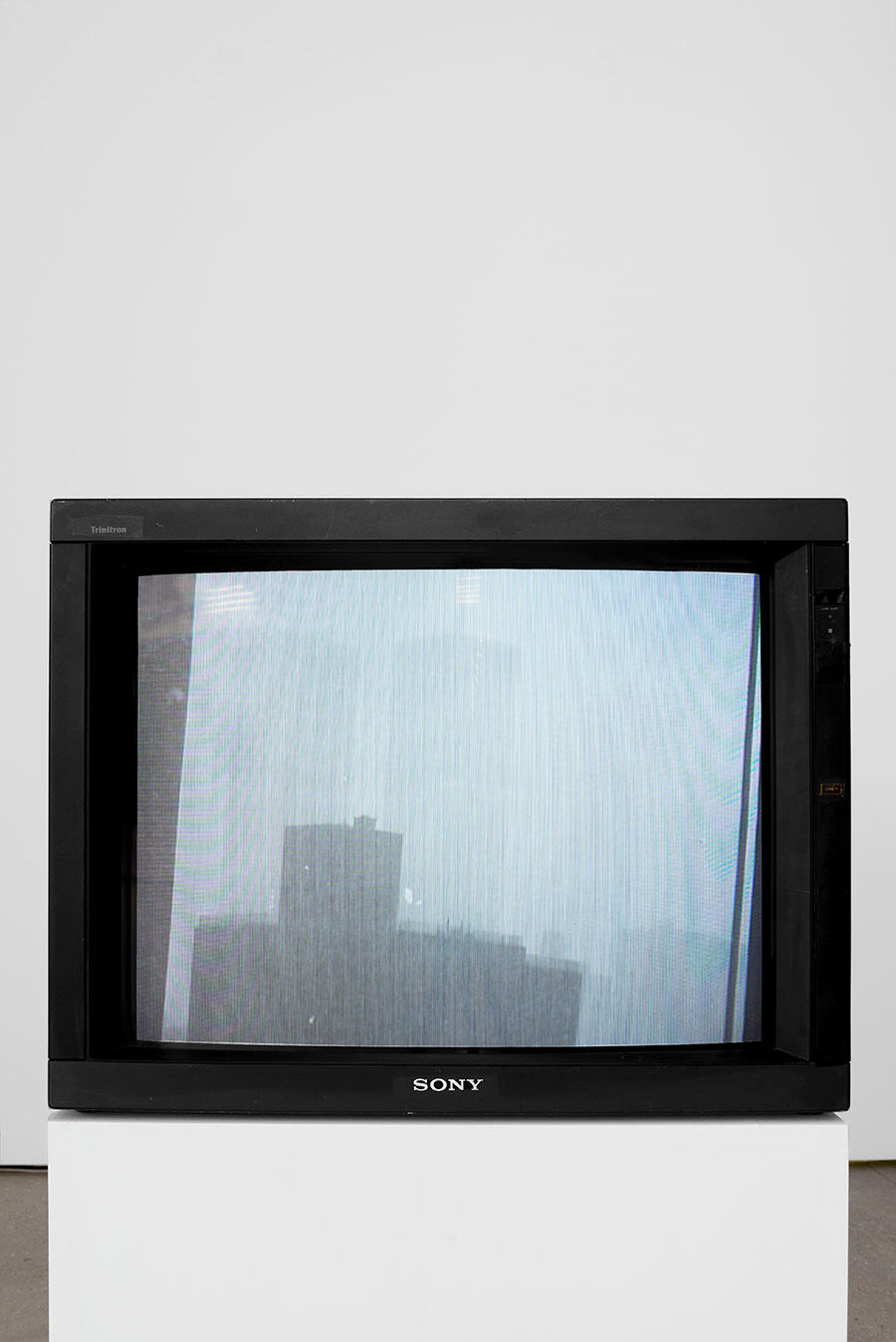

Bonino and curator Catherine David have also included works by historical and contemporary artists known for exercising a similar approach to traditionally ‘poor’ materials. Two works from Matt Browning’s ‘Plastic Freedom’ series (2022–ongoing) – palm-sized, mirrored panels made from plastic bottles, heat-shrunk in layers, one atop the other – are displayed among Bonino’s wall-mounted sculptures. On a nearby plinth, a pair of knitted nylon slippers by Marisa Merz are pierced by rusting iron nails (Untitled, 1968). Snow (1999), a silent, looping film by Lutz Bacher, depicts snowfall in New York, with the monolithic World Trade Center towers looming in the background.

While at first Bacher’s work may feel materially incongruous among the other objects, its documentation of something now disappeared emerges as vital, cutting to the core of what also makes Bonino’s practice so compelling. In Bonino’s hands, a fragile object’s evanescence feels not oppositional to the value of its existence, but rather one of its most enduring hallmarks.

Beatrice Bonino’s ‘In the main in the more’ is on view at Fondation Pernod Ricard, Paris, until 31 January

Main image: Beatrice Bonino, ‘In the main in the more’, 2025, exhibition view. Courtesy: the artist and Pernod Ricard Foundation, Paris, 2025; photograph: Simon Rao