Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo Are Not a Double Act

A blockbuster exhibition at NGV Melbourne pairs two of the 20th century’s most influential fashion designers. But do such singular iconoclasts belong together?

A blockbuster exhibition at NGV Melbourne pairs two of the 20th century’s most influential fashion designers. But do such singular iconoclasts belong together?

The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) has a long history of presenting fashion exhibitions as part of its annual blockbuster programme. Reflecting, in part, Melbourne’s rich fashion culture and the appetite of its audiences, the gallery’s programming over the past decade has included exhibitions on Gabrielle Chanel (2021), Alexander McQueen (2022), Viktor & Rolf (2016) and Jean Paul Gaultier (2014). The latest offering in this vein brings the five-plus-decade careers of Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo into conversation.

Westwood and Kawakubo were born one year apart, in 1941 and 1942 respectively, and are both self-taught designers without formal fashion education. The exhibition opens with a chronology of their lives and work, highlighting significant milestones. Kawakubo was born and educated in Japan and established her label and boutique, Comme des Garçons, in her native Tokyo in 1975, before expanding to Paris in 1982. Westwood was born in a small town in Cheshire and moved to London with her family as a child, opening her first boutique, Let It Rock, in 1971 with her then partner and creative collaborator, Malcolm McLaren. By setting the two women within their broader historical, social and political contexts – details emphasized by pull quotes on the wall – the exhibition identifies areas of commonality.

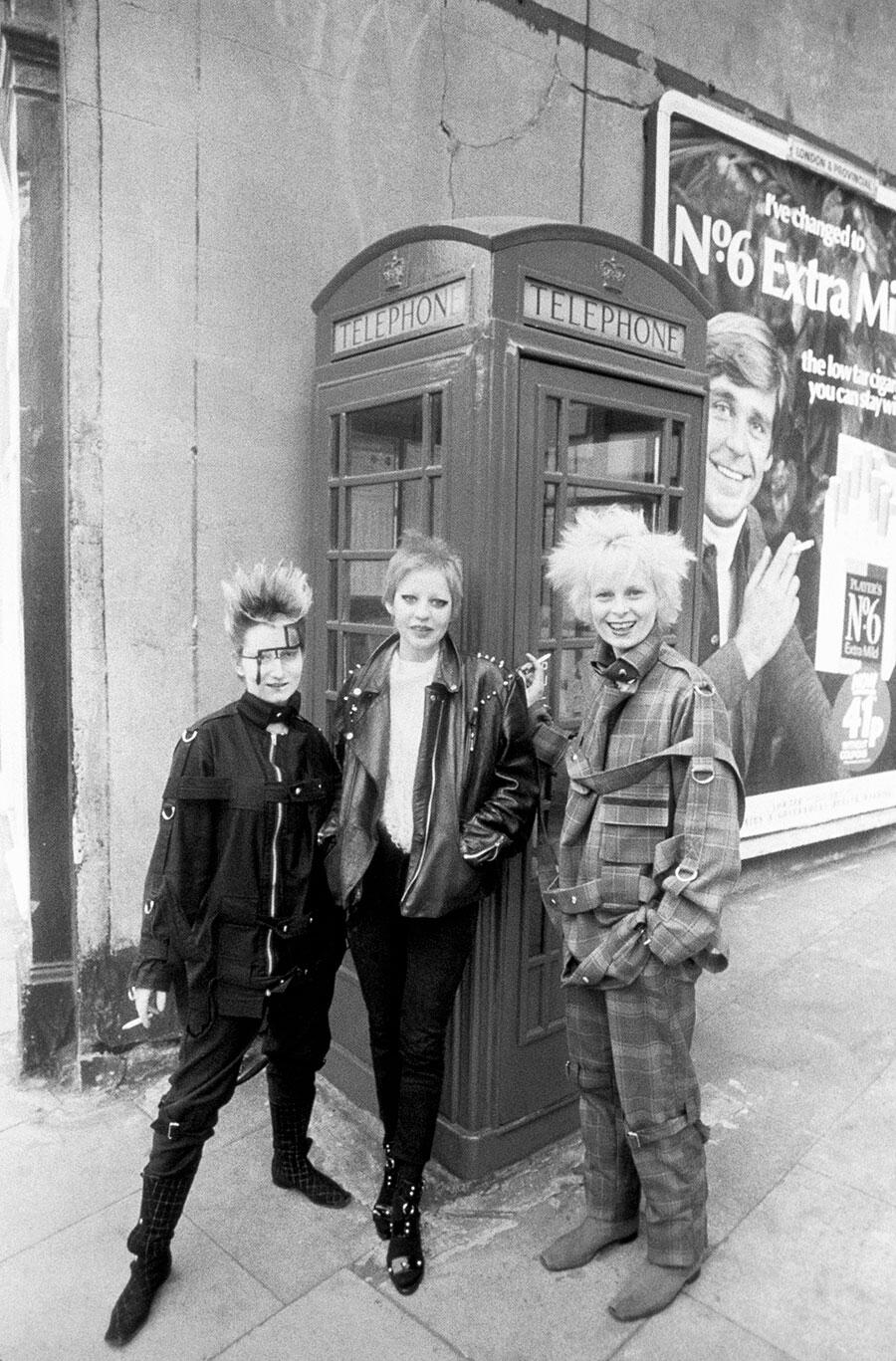

The show, however, is organized not by chronology but by theme. The first section, ‘Punk and Provocation’, for instance, identifies Westwood’s origins in the anti-establishment punk scene of 1970s London, and Kawakubo’s emergence as a disruptive designer against a backdrop of Japanese post-war conservatism. In the thematic section ‘Rupture’, the curators, Katie Somerville and Danielle Whitfield, have paired early Westwood pieces from the 1970s and 1980s with Kawakubo’s designs from the 2000s and 2010s. While these garments do speak to one another across time and space, the wall text highlights a more intriguing commonality that could have benefited from further analysis: both designers debuted collections in 1981 themed around pirates. Whereas pieces from Westwood’s now-iconic collection appear in the show, Kawakubo’s are conspicuously absent. Though runway footage of three early Paris collections can be seen in the ‘Rupture’ section, no garments from the first two decades of her work are present; the earliest piece on display dates from 1996.

Westwood and Kawakubo each warrant their own solo exhibitions because, independently, they are among the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century.

The exhibition includes more than 150 garments, alongside ephemera and runway footage, presented against a bespoke soundtrack designed by Michael Prior. This transforms the gallery space into something akin to a runway show and helps to highlight Westwood and Kawakubo’s fun, expressive style. Westwood’s work is particularly strong in its critique, through appropriation and pastiche, of European classicism and British aristocratic dress. Highlights within the exhibition include pieces from Westwood’s ‘Harris Tweed’ Autumn/Winter 1987–88 collection, which incorporates tweeds, tartans and fitted blazers, as well as several evening gowns that use corsetry to dramatic effect, including the runway version of the wedding dress famously worn by Sarah Jessica Parker in Sex and the City: The Movie (2008). By contrast, the strength of Kawakubo’s output lies in her ability to deconstruct the codes of garment-making and to design pieces intended to be worn on the body in ways that complicate ideas of freedom and expression. Large, obscuring black dresses from the ‘Invisible Clothes’ Spring/Summer 2017 collection, for example, assert how clothing can both accentuate and conceal the female body.

While the show leans heavily into their ‘anti-fashion’ mode of creation and shared desire to rewrite fashion conventions, the double-bill format does not entirely showcase the strengths of either designer. Each is significant enough to carry her own show, and the comparison can feel forced at times. This is perhaps most evident in the final thematic room, ‘The Power of Clothes’, which focuses on the intersection of politics and fashion. Westwood was steadfastly political throughout her career, making her commitments visible in her designs themselves, as in her Spring/Summer 2006 collection, where she presented T-shirts bearing the slogan, ‘I AM NOT A TERRORIST, please don’t arrest me’ – a protest against the UK government’s proposed anti-terror legislation, which allowed for detention without charge. Kawakubo’s politics, on the other hand, are communicated more subtly through her unorthodox approach to garment construction and form. Her recent ‘Smaller is Stronger’ Autumn/Winter 2025 collection, for example, uses fabrics typically associated with menswear to create new versions of ‘power suits’ that challenge the gendered norms of mainstream fashion.

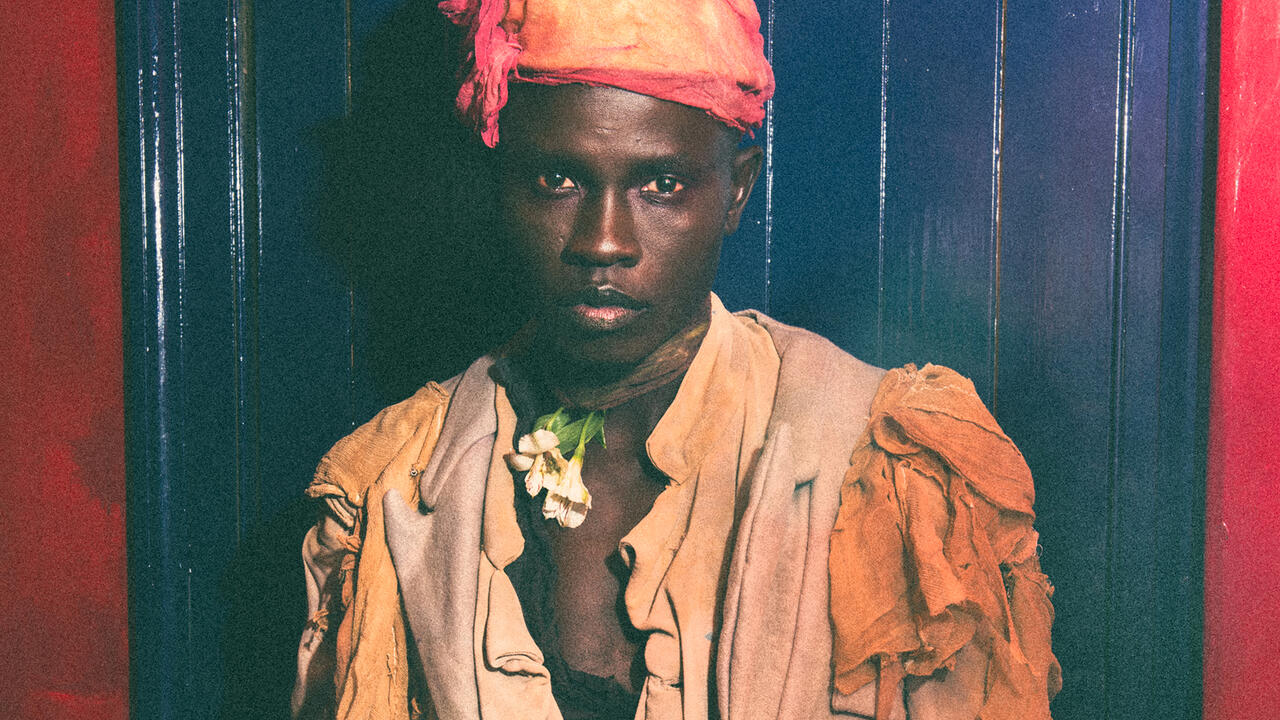

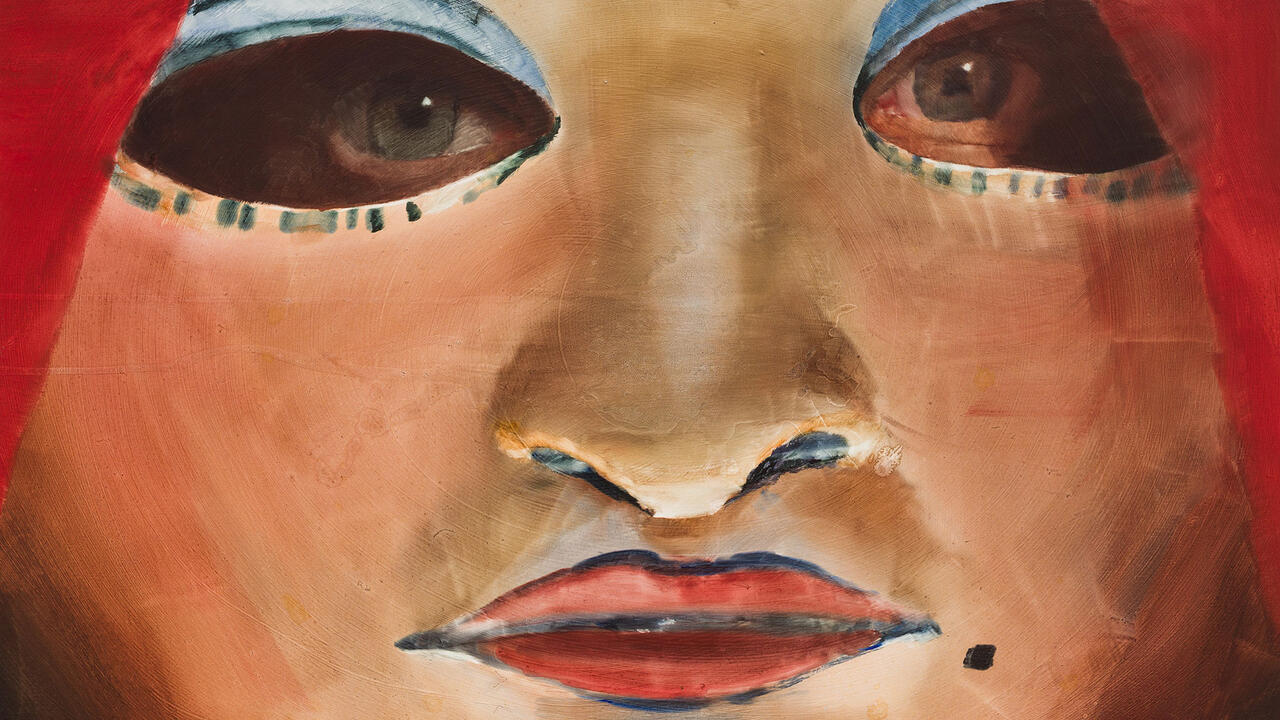

This difference in outward expression or political voice is also evident in the exhibition’s imagery and marketing: Westwood’s face appears on the exhibition promotional materials, whereas a model wearing Comme des Garçons represents the camera-shy Kawakubo, a reflection of the different approaches of the two designers: before her death in 2022, Westwood was very much the face of the operation and its public messaging in a legible way, whereas Kawakubo has often shunned the limelight, allowing her designs to communicate her vision.

In a curatorial pairing such as ‘Westwood | Kawakubo’, there is a risk that the exhibition becomes less the sum of its parts and more focused on what is missing in the overlap. Westwood and Kawakubo each warrant their own solo exhibitions, not only because they are two leading women designers following a series of fashion exhibitions at the NGV primarily focused on their male counterparts, but also because, independently, they are among the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century. The exhibition’s strengths lie both in the works themselves and in the imaginative power of the designers on full display. There is no doubt that they have reinvented fashion conventions, and the exhibition leans heavily into their playfulness to underscore their contemporary relevance. However, the insistence on finding shared themes defies the iconoclastic approach that has made these designers household names and fails to give adequate space to the breadth of their respective creative visions.

‘Westwood | Kawakubo’ is the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, until 19 April 2026

Main image: ‘Westwood | Kawakubo’, 2025, installation view. Courtesy: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; photograph: Sean Hennessy