The Trouble with Writers’ ‘Real Names’

A new publishing project misunderstands the anti-patriarchal motivations behind historical pen names

A new publishing project misunderstands the anti-patriarchal motivations behind historical pen names

In August, the drink company Baileys launched the publishing project Reclaim Her Name in collaboration with the Women’s Prize for Fiction. The idea: take 24 books by women writers who historically published under male pseudonyms and reissue them for free online under the authors’ ‘real’ names as a gesture of female empowerment. Baileys argued that doing so was a way to give women ‘the credit they deserve’, yet assigning identity is a complex issue. Reclaim her name, we might ask, on what grounds and for whom?

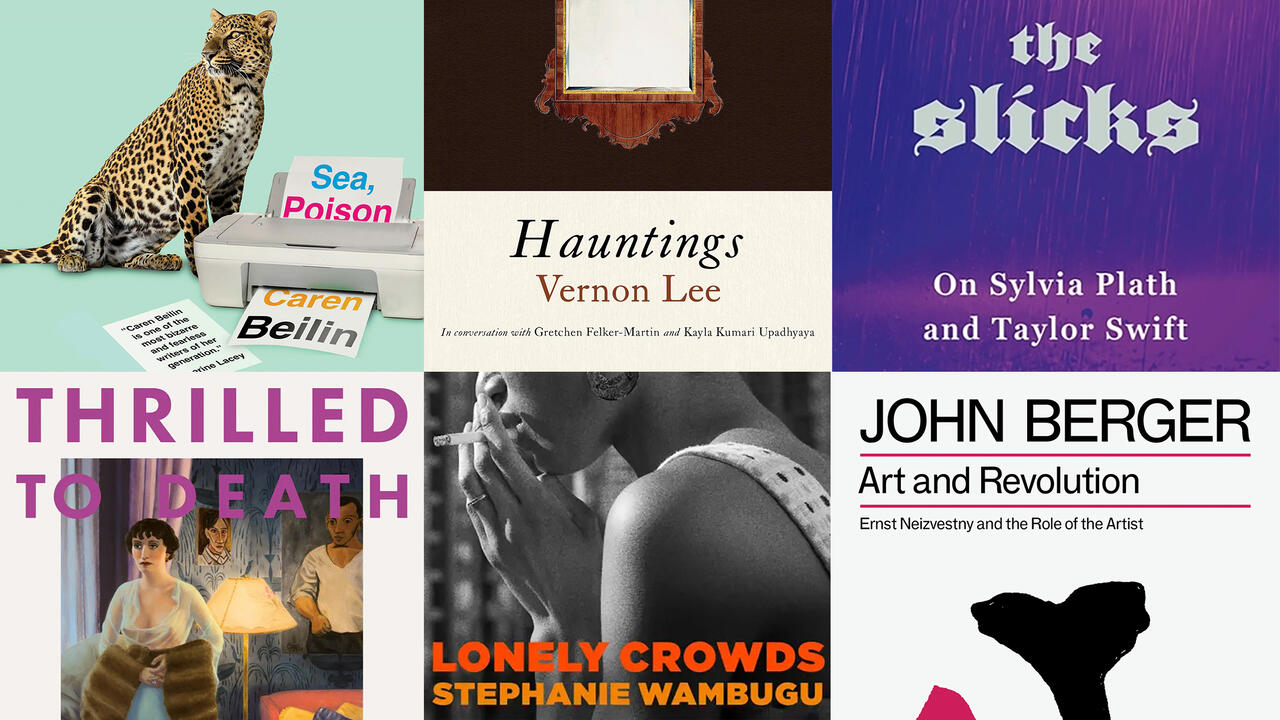

Throughout history, male pen names have helped open doors for women writers in societies inclined to think little of their intellectual capacity. According to the historian Kathryn Hughes, in Victorian Britain being too ‘well educated’ was considered by some an unnatural quality – capable of repelling husbands and shrivelling ovaries. Yet, ignoring a writer’s choice of name and replacing it with their legal designation – itself a patriarchal convention for attributing women to fathers and husbands – hardly amounts to righting a historical wrong. A particular irony of this project is that it submits writers to precisely the sort of limited notion of gender from which they often sought to depart. Take Vernon Lee, an intellectual polymath who wrote everything from supernatural fiction to elaborate theories of aesthetics and psychology, whose book A Phantom Lover (1886) is republished under her birth name, Violet Paget. A lesbian who eschewed women’s clothing for suits and ties, Lee was known to close friends as ‘Vernie’. To borrow a term from Eileen Myles’s Chelsea Girls (1994), there is little to suggest she would have appreciated the appellative ‘womanning’.

Among the other names subjected to questionable restoration is Amantine Aurore Dupin, better known by her nom de plume George Sand, whose novel Indiana (1832) is being reissued. A prolific writer, Sand is famous for renouncing conservative ideas of the role of women: she smoked in public (scandalous at the time), participated in numerous and much-publicized love affairs, and wrote impassioned criticism of inequality in 19th-century France. She also used her pen name in private correspondences, including with her friend and fellow writer Gustave Flaubert. Where, then, ought the project of feminization stop? Should the moniker be redacted from her personal letters? Should her portraits be edited, her trousers replaced with skirts, her cigarettes with embroidery needles? The answer, of course, is no. Like Lee, Sand may have adopted her name to get ahead, but she also inhabited it, grew with it and, along the way, it became a part of her. Inhabiting male characters is also a key aspect of her writing. Indiana, for example, is told from the perspective of a young man named J. Néraud. In the book, Sand frequently breaks from the story to address the reader ‘man to man’, mobilizing the narrator to draw attention to the unequal lot of women. Rather than a mark of oppression hanging over the author’s legacy, her adoption of male personas could well be viewed as a tool for undermining the patriarchy.

In recent years, as identity has become the dominant political and cultural paradigm, a long-held fascination with the private lives of artists and writers has assumed new dimensions. While there is much to be gained from attending to context, a narrow-minded desire to fix ‘truths’ about cultural figures has emerged – one that encourages historical over-simplifications, disregards the nuanced relationship between private individual and public persona and leads down the path to essentialism. We need only recall the debacle over Italian author Elena Ferrante, whose use of a pseudonym has been taken by some as a provocation to hunt the author down – a pursuit mired in an unsavoury interest in disclosing her ‘real’ gender.

‘It is a narrow mind which cannot look at a subject from various points of view,’ George Eliot wrote in the novel Middlemarch (1871–72), reissued by Reclaim Her Name under the name Mary Ann Evans. Despite revealing her birth name in 1859, Eliot continued publishing under her nom de plume until 1878, shortly before she died. She was not some damsel in distress, waiting for a future generation to restore her female honour. Like the rest of the authors gathered by this supposedly emancipatory project, she was an agile thinker and a sophisticated communicator who thrived in adverse conditions. Simplifying her story in order to appear as her deliverer has little to do with freedom. On the contrary, it is the imposition of another cage.

Main image: John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Vernon Lee, 1881, oil on canvas, 52 × 41 cm. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons