Nicolas Party’s Sensuous Reimagining of Art History

His referential grottoes, forests, glaciers and mythical islands seem playful at first, yet closer attention reveals environments charged with psychological unease

His referential grottoes, forests, glaciers and mythical islands seem playful at first, yet closer attention reveals environments charged with psychological unease

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 256, ‘The Shape of Shape’

Hardly anyone considers Renoir’s fish. ‘You think about the weird ladies and the flowers,’ Nicolas Party tells me at his Brooklyn studio. ‘He has terrible taste; his mark-making is awful. He’s sort of the opposite of an artist’s artist.’ Yet when Party spotted one small painting for auction at Sotheby’s, Poissons (Fish, c.1915), he was immediately transfixed. A modest but intense canvas depicting a pile of dead fish, its uncharacteristically saturnine palette recalled, for Party, Francisco Goya’s gruesome images of butchered animals made during Spain’s Peninsular War (1808–14). ‘I thought, this is a fantastic painting, actually,’ he says. ‘I find it very sinister.’

The Swiss-born artist is renowned for his vibrant colour play and distinctly modern treatment of traditional subjects: still lifes, portraits, landscapes. His profound quotational instinct ranges from the caves of Lascaux to the surrealists, with pit stops almost everywhere in between. ‘When you look at an artwork from the past, you feel that time becomes much more elastic,’ Party told Spike Art Quarterly in 2015. ‘Time and history become a “zone” where you can travel.’

Known to eschew white-cube settings for his exhibitions, Party often paints immersive murals – a nod to his early days as a graffiti artist when he learned to execute large-scale designs at breakneck speed. While his grottoes, forests, glaciers and mythical islands scan as playful, enticing scenes, closer inspection often reveals trickier, more psychologically charged environments.

Fanged stalactites hang in shaggy layers like a lamprey’s ringed teeth or the proscenium of a cavernous theatre. Red Forest (2022) is the most straightforwardly representational – mistakable for photojournalism on wildfires – but his abstracted sylvan idylls recall René Magritte and Dr. Seuss in equal measure. In an interview with Stéphane Aquin or Party’s 2022 Phaidon monograph, the artist said: ‘I like the idea of walking through a forest made up of every single tree ever painted by humans, with all their different shapes and meanings.’

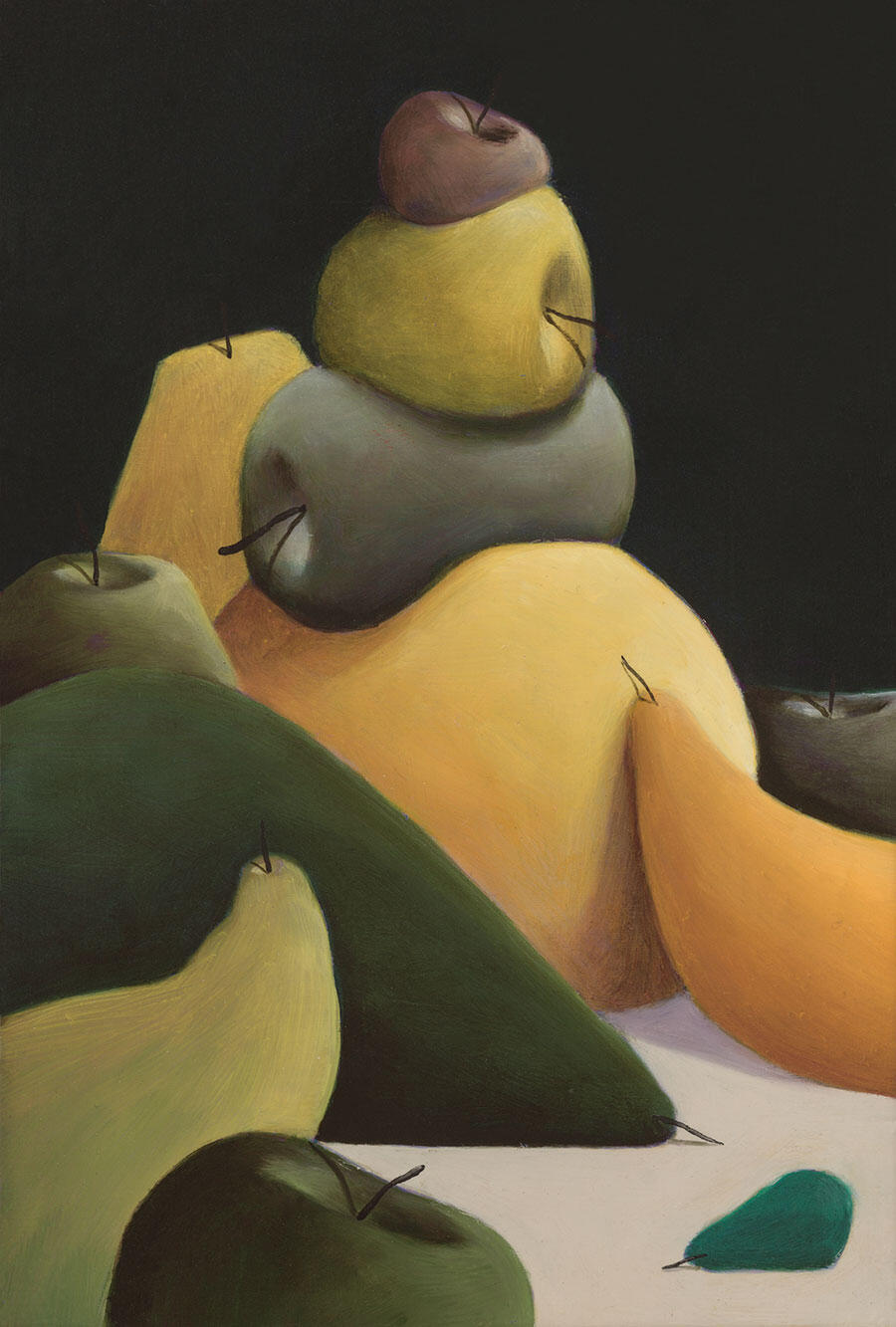

Party’s oeuvre possesses a striking graphic quality, tempered with menace and melancholy. Simple forms strategically arranged have the visual impact of quattrocento frescoes or Byzantine mosaics. His portraits are often flattened to archetypes – woman, man, child – or endowed with fluid, nearly interchangeable identities, like mannequins in a holiday pageant. Their pyriform coifs and flamboyant headdresses are curiously stately; a discreet confidence furnishes their vacant stares.

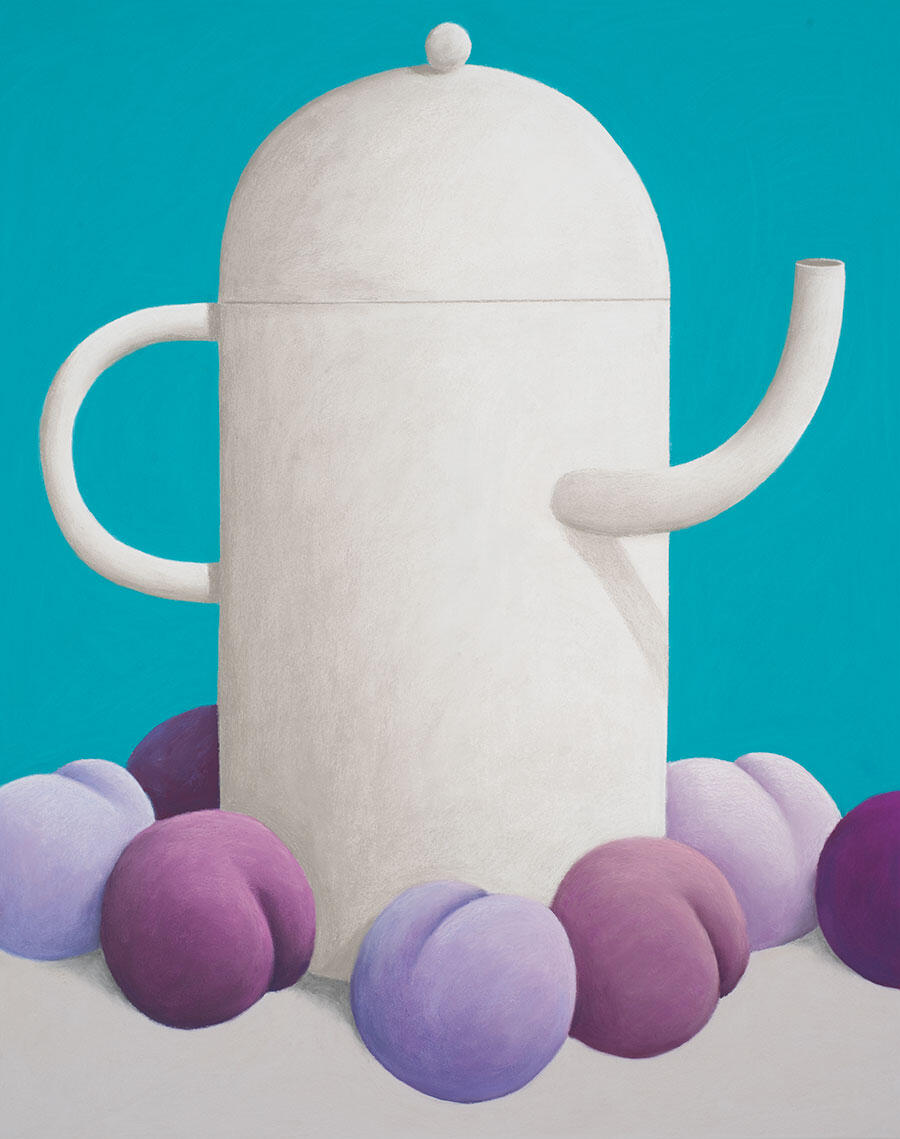

Shapes, in Party’s hands, are inherently erotic. The sinuous, serpentine line prevails, often in stark contrast to rigid geometries. Like Giorgio Morandi and Philip Guston, Party has a cast of enchanted objects that comprise a theatre of polymorphous perversity, rife with sly innuendoes and double entendres. Slumping pears and pert peaches are recurring motifs: their stems and clefts are suggestive, tactile, while their sagging flesh intimates the gradual comedown of post-coital bliss. One painting of peaches (long signifiers of women’s genitalia and young men’s rears) strewn around a teapot with an erect spout invites speculation while allowing for plausible deniability.

Party’s omnivorous intelligence for materials – from pastel and charcoal to copper, marble and wood – is born of a quiet determination to apprehend the full extent of a medium’s expressive potential. After encountering Picasso’s Tête de femme (Head of a Woman, 1921) in 2013, Party took up pastels, a finicky medium denigrated for its association with rococo frivolity and feminine decadence due to its popularity among women amateurs in 18th-century France. Undeterred, Party grew enamoured of its lustrous effects and ease of application. Pastel sticks are ‘just dust’, according to Party in his monograph – pigments suspended in binder. They are maddeningly fragile; even the slightest movement can alter an image forever.

In 2019, the FLAG Art Foundation, New York, invited Party to curate an exhibition of pastels. ‘Pastel’ presented a splendidly heterogeneous array of artists, from Rosalba Carriera and Marsden Hartley to emerging talents like Louis Fratino and Toyin Ojih Odutola. Rounded archways framed the galleries, with several walls overtaken by Party’s ambitious, hand-drawn murals inspired by François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. These centuries-spanning juxtapositions proposed art history as an ongoing dinner party or salon, a space of friskily promiscuous communion where ideas are exchanged and reinvigorated through trans-temporal encounters.

Another eye-catching commission was Draw the Curtain (2021), a 250-metre digital collage printed on scrim that sheathed the famously doughnut-shaped Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. Partially obscured behind trompe l’oeil curtains, a jewel-toned frieze of androgynous figures surveyed the US capital. The colossal scale was new for Party. ‘A month after accepting the invitation, I was like, oh, this is a terrible idea,’ he tells me. ‘If it’s bad, it’s so visible!’

Shapes, in Party’s hands, are inherently erotic.

Recently, his sense of scale has shifted once again. This summer, Party probed the historic collections of the Holburne Museum, Bath, in ‘Copper and Dust’, an exhibition that deepened his engagement with oil on copper. The medium affords painterly precision and a marvellous impression of inner luminosity; historically, high production costs kept many of these works small. This intimacy appeals to Party. He has installed a dentist’s magnifying lamp above his desk and spends hours hunched over copper sheets, finessing the details.

Among the most fabulous copper works are his hinged triptychs and folding altarpieces. The panels feature his signature enigmatic figures – statuesque and saintly, sombre as Fayum mummy portraits – flanked on either side with landscape vignettes. In one brilliant example, snails occupy the wings, seemingly suspended by their own mucus trails (Triptych with Snails, 2022). The wooden cabinet is painted to resemble black marble inlaid with pietra dura designs of elaborately modelled conch shells: an exquisite, austere Kunstkammer with an otherworldly, modern interior.

Party’s upcoming show at Karma in New York will extend this body of work, using Renoir’s fish paintings as its unlikely springboard. Researching Renoir’s catalogue raisonné, he counted 41 paintings of dead fish, most completed during World War I. ‘I want the fish to be part of my family,’ Party says. ‘Sometimes the subject that you choose, or the new theme, it resists you – but I’m not pushy if it doesn’t work.’ Although Party rarely paints from life, he now feels unexpectedly drawn to verisimilitude: ‘I’m gonna go to Chinatown and buy some fish and make my studio smelly.’ Will he succeed in folding them into his iconography? He shrugs and laughs. ‘You’re witnessing an artist on the verge of trying to adopt a new child’.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Dare to Paint a Peach’

Main image: Nicolas Party, Red Forest (detail), 2024, soft pastel on linen, 135 × 142 cm. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Adam Reich