The Mandrake: An Oral History of a Los Angeles Art Bar

How a DIY Culver City watering hole, opened by New York artists in the early 2000s, became LA’s art-world gathering place

How a DIY Culver City watering hole, opened by New York artists in the early 2000s, became LA’s art-world gathering place

Champion Fine Art Comes to Culver City

Drew Heitzler It starts with Champion Fine Art, an artist-run gallery that my wife at the time, Flora Wiegmann, and I ran out of our loft in Williamsburg, New York. This must have been in 2002 or 2003. We had no budget. The idea was 21 shows, counting down to the last one, and then we’d close. It was a nightmare scenario in terms of our bank account.

Halfway through, Flora got into UCLA for graduate school in 2004, so we moved Champion to Los Angeles. We didn’t know anything about LA, but the artist Tony Matelli told us to call his old assistant, Matt Johnson, who’d just graduated from UCLA and was showing with Blum & Poe. Matt told us, ‘Blum & Poe just moved to this nowhere neighbourhood called Culver City.’ So, we found a cheap duplex on Comey Avenue, lived upstairs, turned the kitchen into an office and made the ground floor the gallery.

Flora Weigmann Our apartment in Culver City, where we opened Champion, was just behind where the bar ended up being. We started hosting shows, and then we met Justin [Beal] through friends. Justin and Drew started working together, doing installs for galleries in the neighbourhood. We got to know some of the owners. It was a really close-knit art centre for a while on La Cienega Boulevard.

Justin Beal Drew and I were both working as art handlers for MC [2005–07] – previously The Project – which was a joint venture between Christian Haye and Michele Maccarone. Their installs were always so elaborate – like, building some giant wall with five projectors in it or something. That’s where we met and originally talked about opening a bar. In my recollection, we were walking to get lunch and walked by this former bar.

Heitzler When we closed Champion in 2005, after the last show, Flora said, ‘The next thing we do has to actually make money.’ We thought maybe a commercial gallery, but neither of us wanted to sell art. We’d both bartended in New York – I’d worked at CBGB in college – and one day I was skating down La Cienega Boulevard and saw a ‘For Rent’ sign on this old bar.

The Money

Heitzler One night, the gallerist Anna Helwing – whom I worked for briefl y – had a holiday party, and Jeff Poe was there. I didn’t know him. People were asking what we planned to do aft er Champion and I said, ‘We’re thinking about opening a bar.’ Within two minutes of me saying that, Jeff said, ‘Where?’ I told him it was right down the street from his new space, and he said, ‘You rent it. I’ll get you the money.’

Jeff Poe The real estate broker for the building was the same person who sold us the gallery. I’d grown up with the guy – Greg Batiste – since we were four years old. The building was actually going to be leased to the next-door neighbour, and Greg was able to talk to the owner of the building and persuade him to lease it to Justin, Drew and Flora. Without Greg I don’t think there would have been a bar, quite honestly.

Weigmann Through the grapevine, people on the block heard that we’d looked at the space. Th en Jeff said he could help us get investors. We decided to research what it would take to apply for all the permits.

Heitzler Many of the galleries on the block invested. The whole neighbourhood had ownership of the place.

Tim Blum Jeff and I gathered the investors together – not all of them, but many. Art world collectors, you name it. The Hollywood executive David Hoberman was an early investor. The curator Silka Rittson Thomas, the art collector Dean Valentine – they invested. I don’t have the laundry list, but there was a fair amount of folk. Jeff and I both kicked in a chunk individually.

Not a Conceptual Bar

Heitzler We were straight up ripping off Passerby, which was Gavin Brown’s bar in the Meatpacking District in New York.

Beal Passerby and the Mountain Bar in Chinatown, LA, by Jorge Pardo and Steve Hanson, were great inspirations. But the Mountain was a different kind of project because it was very much an artwork in this moment of peak interest in relational aesthetics. It was a bar where everyone hung out, but it was also very conspicuously an artwork. That felt like an idea that had been explored already, and in the beginning we were very committed to only hiring artists. That was important to the three of us, and that’s why the early bartenders were Amanda Ross-Ho, Vishal Jugdeo, Lisa Williamson. Diana Nawi counted, too, because she was a curator.

Amanda Ross-Ho They started talking about opening this bar. I expressed my interest right away because I was getting out of school and needed a job, mainly. But they were already friends of mine, and I was interested in what they were talking about and proposing, which was during the ascension of the Culver City gallery scene.

Vishal Jugdeo I started out as a barback under Brian Christian. He was some rocker dude from San Jose, I think. I don’t even know how they met him, but he was really cool. He’d been bartending a long time; he knew what he was fucking doing. He taught me how to be a bartender; he was my mentor.

Lisa Williamson I was in the same MFA programme as Justin at the University of Southern California [USC] – he was a year ahead of me. As soon as I finished – or maybe I was still in school – I started bartending. I knew Drew and Flora well. At that time especially, the Mandrake felt like a small, tight-knit community of artists, so it was a really fun job to fall into. I had no bartending experience, so there was a steep learning curve. We were almost all artists. This really great guy, Brian, might’ve been the only one who was a proper bartender. That’s how I learned to make drinks – it was from him.

Diana Nawi It was my favourite job in the art world. I was working at LAXART as an intern with Shana Lutker, Naima Keith and Aram Moshayedi, and one day, moments after they opened, I walked into Mandrake and asked if they were hiring. I was not the most qualified person, so they gave me a slower shift. But it was nice. After my shift, every gallerist got off work and would come in – just a locals-only energy. At six, seven, it would start to turn over, but the late afternoon was all gallery people: head of crews, the front desk, directors, etc.

Heitzler We were like, ‘This will be the locus of the neighbourhood.’ We knew. It would be a bar owned by artists on a block with a bunch of art galleries. By the time we opened, there were seven or eight galleries on the block. At its height, there were 30 in the surrounding area. I remember one of the best compliments I had: in the beginning, I worked the door a lot. Gavin Brown was at the bar, and when he came out he said, ‘I like your bar, Drew.’

The Buildout

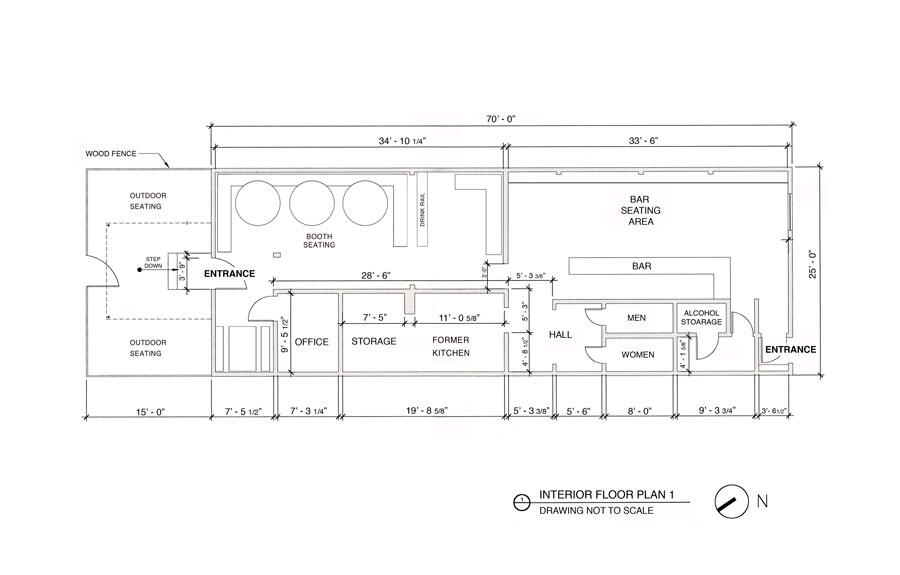

Beal I can probably tell this story now, because enough time has passed. We did the whole buildout ourselves. All the construction. When you’re fi ling for permits, you have to submit drawings, but there was no existing- condition drawing on fi le with the city. So I made a CAD drawing of what we wanted the bar to look like, crumpled it up, spilled some coffee on it, flattened it back out and took it to the building department, saying it was the existing conditions – which is insane, but I was 27.

They said, ‘Well, if that’s how it is, you don’t have to change anything.’ So we boarded over the glass-brick window, and the three of us did the work at night. I’d drawn the plans, but then you’d realize a pipe was over here instead of there, so you’d move the sink, redraw it and build it that way. Flora did all the tiling. We did everything – every surface, every wire. It really was a full DIY build, the kind of thing that probably couldn’t happen now.

Heitzler The three of us literally built the bar – no permits, no contractor. That was Justin’s architectural mind at work. He designed it; I did the electrics. It actually seemed possible back then in LA – you could just go in and make a place with your friends.

Weigmann The three of us rented the space. Justin and I were both in grad school – he was at USC, I was at UCLA – so we’d go to class during the day and work on the bar at night. It was exhausting but exciting; the space was raw, just concrete floors and drywall dust.

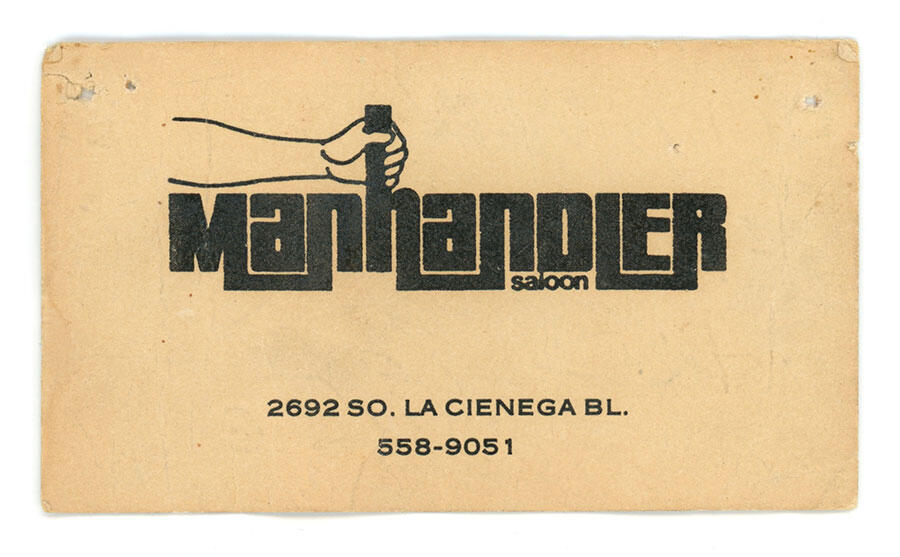

Heitzler When we first started clearing the space, we found what looked like a time capsule buried in one of the walls – a sealed box, maybe from the 1960s or ’70s, full of old business cards from previous bars in the space, a matchbook from the Manhandler [another former occupant of the space], a menu and a photograph. It felt like a message from the past lives of the building, a reminder that this place had already been many things before us.

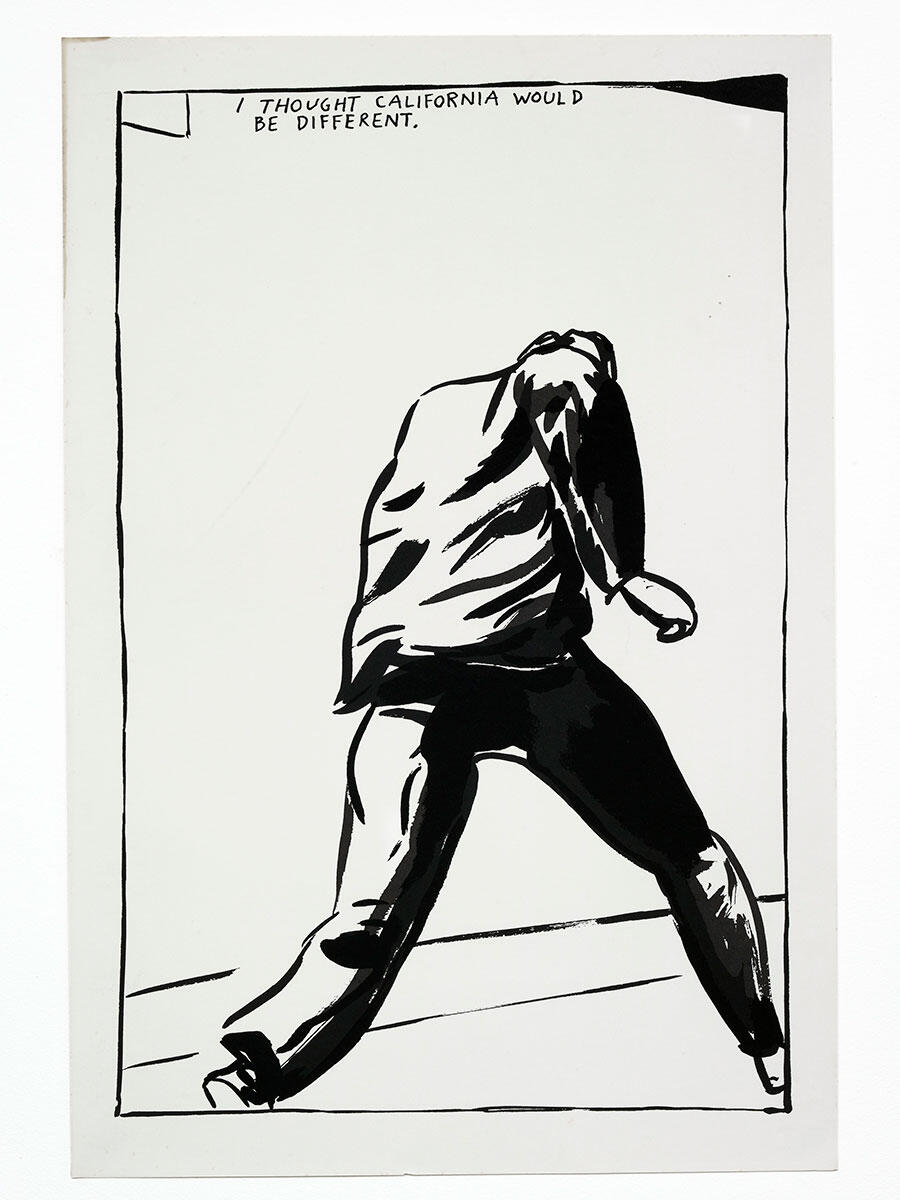

Beal We’d actually come in under budget on construction, and I remember Drew, Flora and I went out to celebrate. We went to a charity auction and that’s where we saw the Raymond Pettibon piece, I Thought California Would Be Different [1992]. We said let’s spend the money on that, and we won it at the auction. Th at really became a kind of motto for the place. Even now, people tell me their first memory of the bar is that piece.

Jim the Ghost

Heitzler The building had been a gay bar since the 1960s, which we only found out later. In the ’80s it was a leather bar called the Manhandler; later it became Maverick’s, a gay cowboy bar, but before that it was BJ’s, and even before that JJ’s Irish Pub, ‘Where Irish Guys Are Smiling’. JJ’s was run by Seamus, who worked the bar, and his boyfriend, Jim, who worked the kitchen. Jim was our ghost. He haunted the place, but he was friendly. A friendly ghost.

When we were building the bar, Justin took a picture, and in one of the doorways there was this apparition. He joked, ‘Hey, look, the bar’s got a ghost.’ One night after we opened, an old-timer from the neighbourhood came in and started telling Justin about the history of the place, all the way back to the 1960s. Then he said, ‘I was here the night Jim died.’ Jim had come out of the kitchen near closing, stood in the doorway and had a heart attack – he died right there. It turned out to be the same doorway from Justin’s photograph. Years later, that story showed up in a book about haunted bars in Los Angeles [James T. Bartlett’s Gourmet Ghosts: Los Angeles, 2012].

Beal I’d drive over after crits at night to hang dry-wall – completely alone, at one or two in the morning. I set up my new SLR camera to test exposures and took about a hundred photos of the same spot. When I looked later, one image was different. There was an apparition, clear as day, exactly where Jim had died. A sort of foggy, dome shape – an upside-down parabola. It was really weird. I told Drew and he said, ‘Don’t ever talk to me about that again.’

And the thing is, Jim kept coming up over the life of the bar. Once the alarm went off but none of the doors were breached – little things like that. It became a deep part of the mythology.

The Name

Poe I wanted to call the bar ‘Buttons’.

Heitzler We were struggling with the name, and one day, during the buildout, the photographer Christopher Williams stuck his head in and said, ‘You should name the place the Mandrake.’

Weigmann It was still unnamed when we first opened. We didn’t even paint the bench; it was just primer white. The bar was plywood, maybe with a coat of Varathane. We’d leave scraps of paper around and ask people to write down ideas. Everyone who came in would scribble something.

Beal Once we’d decided the bar was really happening, we had these pieces of paper everywhere. Everyone would be drunk and writing suggestions – some smart, some stupid. I still have a binder full of them. A few were: The Eleventh Finger, The Thirteenth Step, Mansfield Bar – after Jayne Mansfield was decapitated in an accident. But Chris Williams had been talking with us about names. He once suggested ‘Civilization and Its Discotheques’, an idea he got from [critic] Diedrich Diederichsen. But one day he just walked by the space, poked his head in and said, ‘Mandrake’. At first everyone thought the name was terrible. Now, it feels inevitable. And it was never really resolved whether it was Mandrake or The Mandrake.

Blum For the record, it wasn’t Chris’s idea; it was his wife, Ann Goldstein, who suggested it to him, who herself got it from Hamza Walker’s email address.

Hamza Walker It was funny because I’d used the name Mandrake for years. I was a DJ at WHPK, the University of Chicago radio station, and took it from a Tales from the Crypt episode – there was this radio host named Mandrake whose caller turned out to be Satan. Later, when I got email, I used Mandrake [as my handle].

Soft Opening

Weigmann While we were doing the licence applications, we turned it into studios because we needed to get a little money coming in. So there was already something happening before it ever became a bar. Was it called The Backroom? Some other people did a little gallery in the front, in what would become the bar, and we had two artists renting the back as studio space. It was already activated; people were coming to the shows.

When we finally got the liquor licence, I looked at Justin and said, ‘I guess I’ll go get change for the till.’ We bought booze, got singles and fives and opened the doors. For the first couple of years it felt more like a club-house than a business – quiet, mostly friends. We’d do installations and small performances in the back room before it filled up with nightly traffic.

Jugdeo The bar soft-opened just before my last year of grad school, June 2006. They started letting friends hang out while finishing the buildout. I drove the artist Kelley Walker down to the Mandrake one night – we all had drinks, but it wasn’t officially open. I was on a student visa, and Justin floated the idea that I bartend; eventually I was named the bar’s ‘interior designer’ so I could stay in the country. By that summer I was working legally, and for the next four years that was effectively my job.

Aram Moshayedi Before the renovations, the space was occupied by The Backroom, a curatorial project by Magalí Arriola, Kate Fowle and Renaud Proch that focused on archives and collections maintained by artists. When it turned into the Mandrake, it was basically a friends’ bar; it felt like an extension of grad school. It may have been because Justin and I were at USC together – I was in the art history programme, and he was in studio art – that so many people I associated with school were also regulars there.

Poe I was there that first night. It was just art people, everyone knew each other. Dave Muller was spinning soft, quiet tunes. There was such a sweetness to it.

Heitzler I actually missed the very first night, but by the time I got there, it already had a heartbeat.

Heyday

Beal In the early days, Amanda Ross-Ho and I worked Tuesdays and Saturdays – or maybe Fridays. Tuesdays were dead. No one came in except friends, and you never wanted to charge your friends for drinks. Slowly, though, the place picked up energy.

Everyone drove back then. I remember one night Mischa Barton came in – Lisa was her bartender – and later that evening she got a DUI. We were all panicked, convinced we’d somehow get blamed. It was that kind of time: messy, small, a little reckless but full of life.

Weigmann For the first few months, we didn’t have employees. It was just Justin, Drew and me tag-teaming the bar and everything else. Later came Lisa, then Amanda, then Diana. Some people were just out of school; others still in it. It was the perfect job – you could work in your studio all day and bartend at night. We hosted readings and events, too, which made the job more interesting. The ‘Deleuze A to Z’ ran weekly for months, organized by Hedi El Kholti, who also DJed. David Grubbs played once.

Moshayedi The heyday, for me, was when it wasn’t yet a proper business. The clientele was just friends, students, curators – mostly drinking for free. Vish and I were roommates at the time. I was broke, living on Goldfish crackers and pretzels that I would get from the bar. It felt utopian: a place for people with no money, but an endless appetite for talking about art or anything else remotely related to art.

Firstenberg When we opened LAXART in 2005, just a few doors down, the Mandrake instantly became our second space – really my office. I met artists, curators, donors there daily. The idea for The Occasional Project, which became Made in L.A. with the Hammer Museum, was born at that bar.

Nawi Mandrake was a hub, pure and simple. For me it defined the LA art scene. Years later, when I came back, it had changed – I didn’t know the people anymore – but in those early years it was magic.

Poe In December 2007, I called a ‘mandatory meeting’ at the Mandrake for every artist we represented. Nobody knew it, but we’d just bought the building across the street. We started with drinks, then I said, ‘Okay, field trip.’ Twenty of us walked over to this old navy factory – soon to be Blum & Poe’s new space. That was a Mandrake night: half spontaneous, half legendary.

Theodora Allen Lisa introduced me to Justin via email and I began doing a Friday ‘country music’ happy hour, playing records: outlaw country, cosmic Americana, Bakersfield sound, stuff like that. I was at UCLA at the time and our studios were in Culver City. There wasn’t any money in the gig, unless the bar did exceptionally well. It was about just hanging out, having a drink and listening to music while I waited out rush-hour traffic back to the Eastside. Sometimes it was empty; some- times it was packed. It’s how I first met Jeff, who became my dealer of ten years – an organic connection that likely wouldn’t have been made otherwise.

Ross-Ho One Halloween I showed up in a ‘tasteful’ costume: a fake pregnant belly and a Hooters T-shirt. That night I found myself having a serious conversation with the curator Shamim Momin – then at the Whitney – while dressed like that. I remember Drew interrupting: ‘All right, studio visit’s over, back behind the bar.’ But later Shamim and I worked together on the 2008 Whitney Biennial. Those nights were rowdy, chaotic, magical – moments that don’t happen anymore.

Moshayedi I shared a birthday with Elad Lassry – we called it ‘ELAM’ for Elad and Aram. The artist Lucy Dodd was there. Most of the crowd was pretty respectable, but Lucy was wild. She grabbed a piece of cake, smeared blue frosting across her face like a mask, and started dancing on the floor. It was unforgettable.

Weigmann We thankfully never had any major catastrophes – or deaths like the bar before us. The worst situation was one night an unhoused man staggered in, bleeding. We laid him on the floor, pressed towels to the wound, called an ambulance. He survived. It was one of those nights that reminded you how much life – chaotic, unpredictable – passed through that place.

Dave Muller I painted a mural for the bar – a riff on the Haçienda club in Manchester, mixed with being drunk, maybe more about the art ecosystem. I also DJed with Bob Nickas; we’d go from Sonic Youth to disco, depending on the mood. Total chaos, total joy.

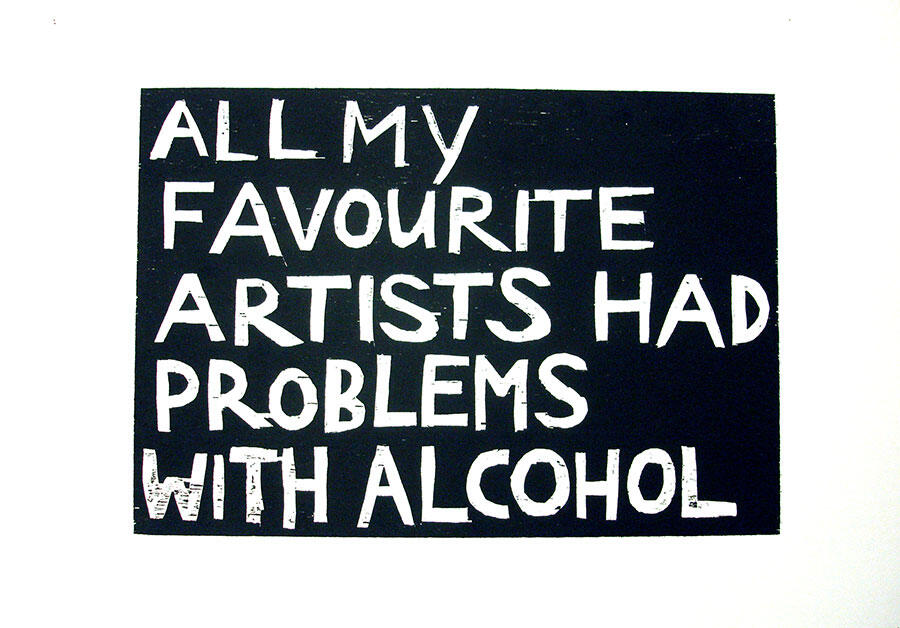

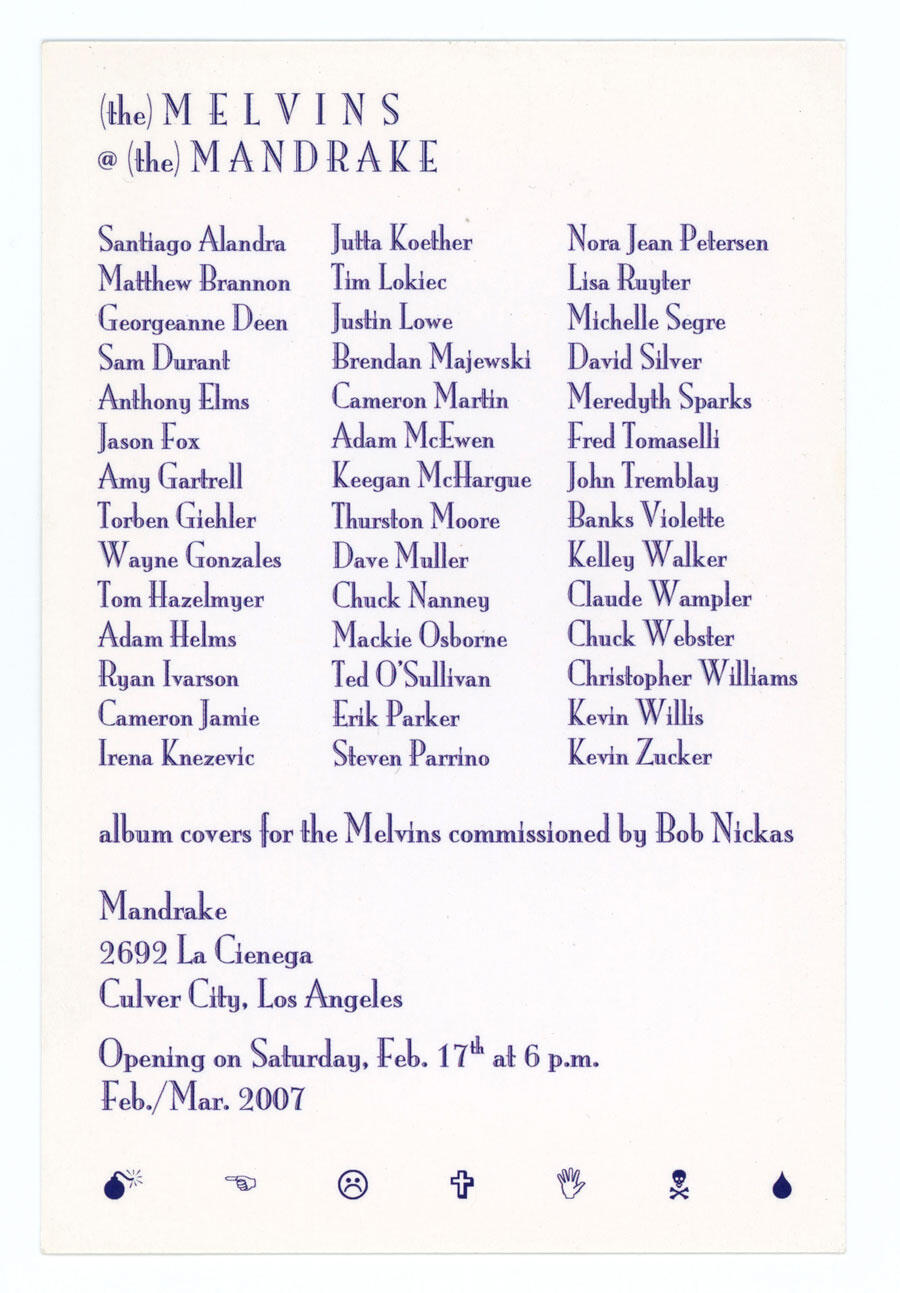

Bob Nickas I knew Flora, Drew and Justin from New York, so I’d head straight to the Mandrake whenever I landed in LA. My best memory was Melvins @ The Mandrake in 2007 – 40 artists made mock album covers for the band. We got the Melvins to play at Blum & Poe for the opening and afterwards everyone came over. Adam McEwen made a piece that said ‘SORRY WE’RE MELVINS’ – it hung behind the bar for years. It had that Max’s Kansas City energy – a real artists’ bar.

Allen Ruppersberg I brought a few old newspaper comic strips of Lee Falk’s Mandrake the Magician – I thought they should have their namesake behind the bar – and a small Al’s Café poster, from the conceptual coffee shop I started in 1969. It just felt right. For me, the Mandrake carried the lineage of LA’s artist-run culture.

Williamson Working with Amanda Ross-Ho was pure joy – she’s so upbeat. When a good song came on, everyone would dance, someone always kicked the cowbell. There was a prom-themed party once – Marisa Tomei and Dita Von Teese showed up. And I actually met my husband LeRoy Stevens there – our first kiss was right out front.

Jugdeo Technically, we closed at midnight on week-days and 1 am on weekends but often stayed open till 4 am. I remember serving drinks while high on mushrooms. It was before LA became a late-night city – there were after-hours spots, but nothing like this. The Mandrake was under the radar, scrappy, experimental. That stretch of La Cienega felt forgotten then, which gave us the freedom to do whatever we wanted.

Last Call

Beal By 2012 I was fully out of day-to-day operations. Flora really carried it. She was committed to giving the bar one final go, and she did an amazing job – getting all the PPP [Paycheck Protection Program] loans and grants during the pandemic, which kept it alive. We even managed to renegotiate the lease. It was still working, so the question was always: why close? There was still this promise of transformation – the Metro finally reaching Culver City, the idea that things might shift again.

Weigmann During the pandemic, Drew and I turned it into a general store for the neighbourhood, selling plants, local food products, bar supplies, and art objects – small things to keep it alive. It became a lifeline, for us and for the community.

Beal But then in 2024, these three younger guys approached us about buying it. Drew, Flora and I spoke on the phone about it, and it just felt right. I was in New York with two kids, Flora was in Washington state, Drew had a kid. It was the right time to hand it over. What I liked was that they didn’t want the name, so we got to sunset it – to let the Mandrake stay with us.

Firstenberg There was a moment, years later, when I tried to walk in with my daughter, who was still a baby, and got turned away at the door. I remember saying, ‘Culver City is officially over as we knew it.’ That sums it up: the Mandrake had already become legend.

Heitzler I was glad we passed it on without passing on the name. In the back room, there used to be a stencilled sign that said ‘No Dancing’. It was a leftover from an old cabaret law. We never enforced it. The irony of that always felt perfect – it was a bar built for movement.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘I Thought California Would Be Different’

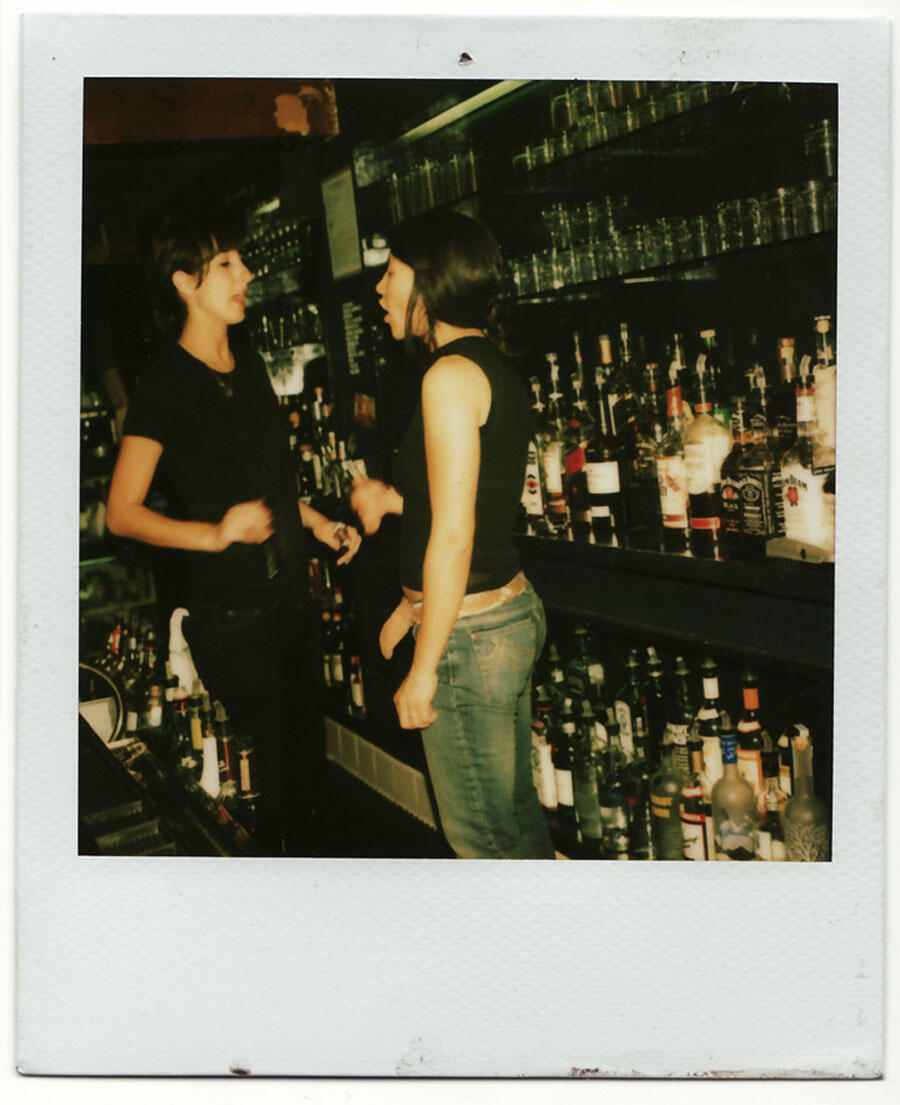

Main image: Interior of The Mandrake (detail), 2017. Courtesy: The Mandrake; photograph: Joshua White / JWPictures