Ulrike Müller’s Abstract Prints Refuse to Settle

In her Vienna studio, Müller navigates the margins of art history, delighting in gaps, absences and overlooked stories

In her Vienna studio, Müller navigates the margins of art history, delighting in gaps, absences and overlooked stories

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 256, ‘The Shape of Shape’

For several years, Ulrike Müller had a light-filled studio in Industry City, Brooklyn, with ceilings so high that she installed a swing. This was before 2013, when the sprawling complex was taken over by developers who turned it into a bland ‘innovation ecosystem’, aka a mall. This past summer, Müller fled the US and moved back to her homeland, Austria. Now, in her new studio-barn, that same swing has made its triumphant return.

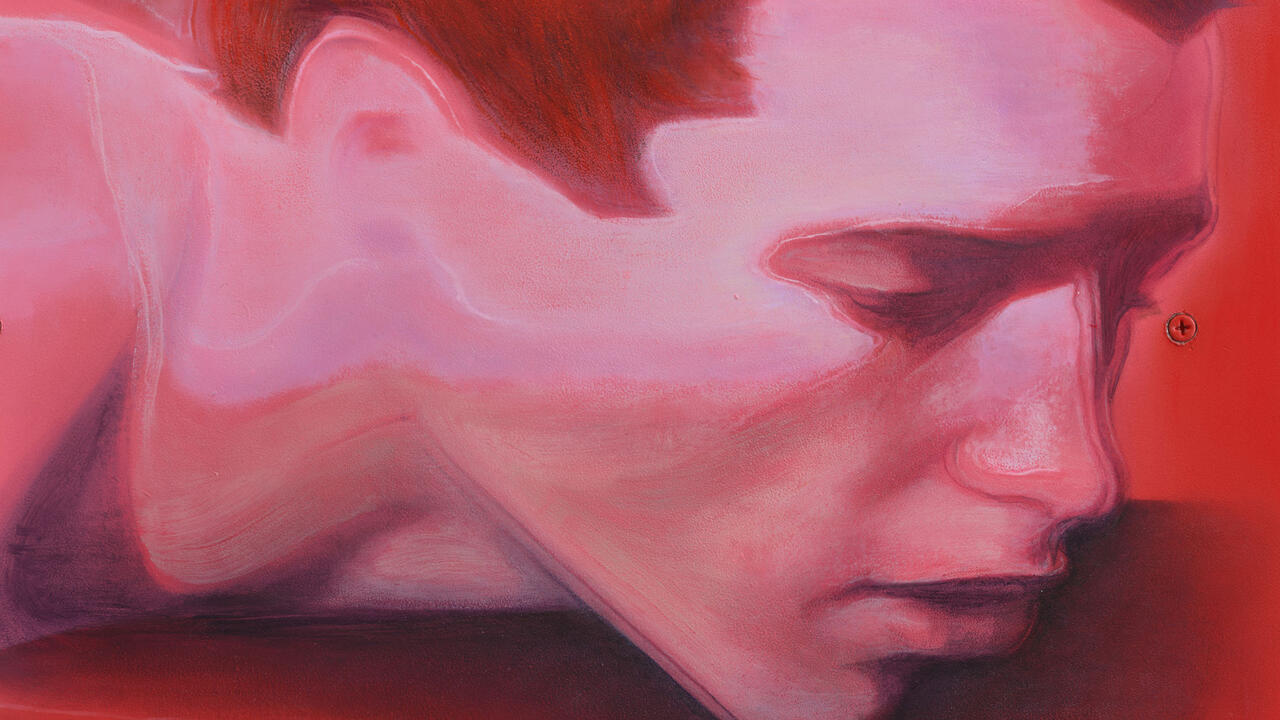

I bring up the swing because when beholding the bold, graphic shapes in some of Müller’s work, particularly in the enamel ‘Hinges’ paintings (2022–23), I often imagine them swaying, shifting and spinning free from their steel supports. Perhaps this is because of the contingent, precarious dance of curvilinear forms meeting hard edges – it always seems like they could easily flip off the wall. But it’s more likely because Müller continually unsettles the figure-ground relationship in her works. By also omitting shadow and chiaroscuro, she allows her flat shapes to feel active and alive. Just imagine what they look like from a swing.

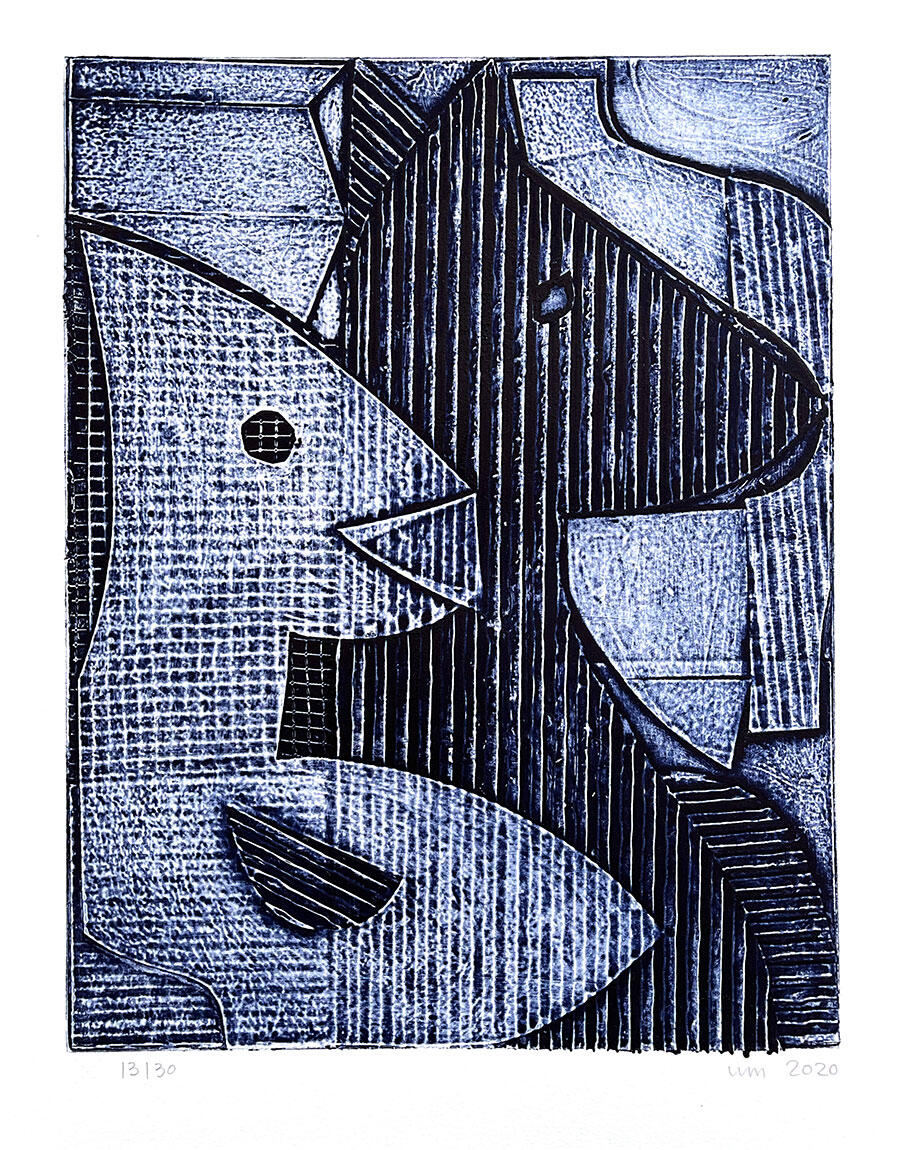

That sense of animation feels more obvious, and explicit, in her monotypes, a medium she began engaging with in 2018 – though her work has always contained the logic of printmaking, where repetition, reversal and touch have long been key. Through their bright shapes and crisp lines, her abstract prints also appear to be moving, never at rest. Collagraphs such as Assorted, Petit Beurre and Filo (all 2020) feature birds, cats and dogs; in the same year Müller created her first large-scale mural, The Conference of the Animals, for a curved wall of the Queens Museum in New York. It happily resided there for two years in an extended residency, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Enlarging her shapes to scale tall walls has become yet another element of Müller’s practice, alongside textiles, drawing, performance and curating. For another two years, the Ludwig Forum in Aachen, Germany, displayed two of her murals, Paper Body (ghost) and Paper Body (pointer) (both 2023), both based on small-scale collages. An accompanying group show across three of the museum’s galleries featured works from its collection installed alongside Müller’s own. The strategy of the installation echoed that of ‘Always, Always, Others’ (2015–16), at mumok in Vienna, which Müller co-curated with Manuela Ammer. That exhibition focused on classical modernism alongside works from the 1970s – both pivotal moments following achievements in abstraction – and asked, when does a non-canonical artist look canonical?

Like Amy Sillman, Müller relishes in pointing out art history’s gaps and omissions. As Sillman writes in a zine accompanying her 2019–20 ‘Artist’s Choice’ show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York: ‘There are so many cracks in it already that at some point it dawns on you that art history might just be wrong, or a mythic fiction made up by certain people, like a religion with its own Kool-Aid.’ The two artists share a feminist perspective that sees them constantly questioning the 20th-century canon, and both have used their curatorial activities to indicate how it is a stealthy fabrication – yet one that it is possible to change.

Müller’s art shows how she, in turn, has been shaped by art history. She studied 1970s abstraction while working on the accompanying catalogue for ‘High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967– 1975’, a show curated by Katy Siegel and advised by David Reed, that toured the US, Mexico, Austria and Germany in 2006–08. From interviewing then-undervalued artists to discovering forgotten works in Jack Whitten’s long-closed storage unit, the experience allowed the influence of painters – Mary Heilmann, Al Loving, Elizabeth Murray and Dorothea Rockburne among them – to seep into Müller’s practice and answer some of her own burning questions, including how the socio-political can bleed into abstraction.

At the time, Müller was active with the queer collective LTTR and was moving from text-based videos and performances to the ‘Curiosity (Drawings)’ (2005–06), a group of 51 symmetrical, vertically divided compositions in pencil and spray paint on paper. The series established an abstract lexicon that eventually led to her enamel paintings. Twenty years later, Müller’s aesthetic vision continues to evolve while at the same time asking: what shape can an exhibition or art take today? By offering beauty, solace, movement and joy, her work offers one clear response.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Swing Time’

Main image: Ulrike Müller, Hinges (detail), 2022, vitreous enamel on steel, 39 × 30 × 2 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Sylvia Kouvali London/Piraeus; photograph: Brica Wilcox