Beverly Buchanan’s Ruins Survive Her

Novelist Stephanie Wambugu considers how the late artist’s eroding land works preserve memory and mark the passage of time

Novelist Stephanie Wambugu considers how the late artist’s eroding land works preserve memory and mark the passage of time

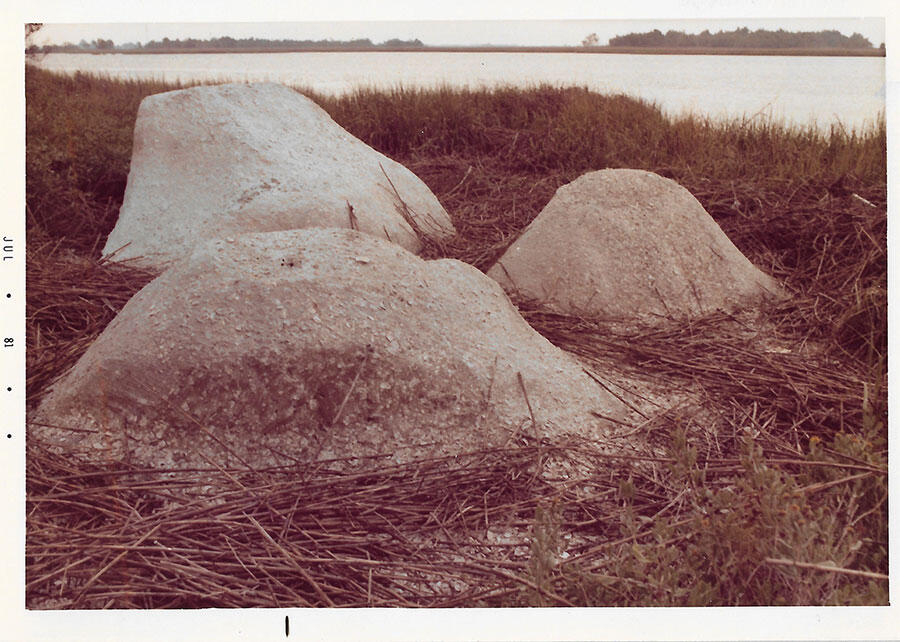

With deceptive simplicity, the late Beverly Buchanan's Marsh Ruins (1981) exist in a state of decay on the southeast coast of Georgia. The sculptural mounds are made of concrete and covered in tabby, a form of cement made from burnt oyster shells, sand and ash, which makes them especially susceptible to erosion: these works are subject to natural forces that will eventually erase them. While she may not have intended this when she constructed them at the age of 41, they appear to be a self-reflexive monument to Buchanan herself, who died in 2015 and whose ruins survive her. They also, like the remnants of any bygone civilization, memorialize the transience of life itself. The routes we take to work, the homes we live in and our places of worship may one day too become detritus, representing a distant past that is unimaginable to members of newer civilizations. Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins help us to consider the elegiac dimension of every artwork, in the sense that they reveal the labour of an artist at a fleeting moment in time. The hours and days an artist spends working accumulate: each completed work brings them closer to the eventuality of their own death.

Born in North Carolina in 1940, Buchanan was taken in by relatives after her parents’ divorce. Her great-uncle and adoptive father, Walter Buchanan, was dean of the agricultural school at South Carolina State College, which was at the time the only public university for Black Americans in the state. She often accompanied her uncle on his travels through the Cotton Belt to visit and advise sharecroppers on their farming practices. These encounters had a lasting effect and prompted the artist’s career-long preoccupation with Southern vernacular architecture. In a 1988 interview with Kellie Jones, the artist David Hammons spoke about his own interest in the regional styles in which Southerners, particularly Black Southerners, built their homes. Hammons refers to ‘that kind of spirit that’s in the South’, going on to say: ‘I just love the houses in the South, the way they built them. That Negritude architecture […] Just the way we use carpentry. Nothing fits, but everything works […] everything is a 32nd of an inch off.’ This particularly Southern architecture is seen also in the small painted models of shacks that Buchanan began making in 1985 – such as Orangeburg County Family House (1985) – as a homage to the people she knew in the Black Belt and their vanishing ways of life.

Buchanan left the South to attend Columbia University, where she received master’s degrees in parasitology and public health in 1968 and 1969 respectively. Following her graduation, she took a job as a medical technologist at the Veterans’ Administration Hospital in the Bronx. Buchanan would have had regular contact with men returning to New York from deployment in the Vietnam War (1955–75). One imagines Buchanan, who would not begin her art practice until the end of the 1970s, absorbing an organic oral history of this contentious and deadly conflict that would have run counter to dominant narratives of the war. Throughout her oeuvre, there is the impression of someone metabolizing major historical shifts witnessed during their lifetime, via the granular.

Beverly Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins help us to consider the elegiac dimension of every artwork.

For the most part, artists make and exhibit works with the hope that they will endure. Conservators and temperature-controlled rooms exist to safeguard objects from degradation arising from exposure to light or the elements. But there are exceptions. Buchanan’s ruins use public space to remind us of life’s impermanence, even as many artists attempt to make art that survives them.

Monuments have long been sites of cultural contestation. In the early 1980s, there were heated public debates about Maya Lin’s chosen design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, which was seen as being implicitly anti-war because it lacked triumphalist or glorifying elements. Confederate statues in the United States have come to function, similarly, as avatars for the racial and political grievances of various groups. When these lively debates – which are ultimately about posterity and memory – came to a head after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, demands for the demolition of statues commemorating Confederate leaders were met through official and unofficial means. Some local governments acquiesced and agreed to remove the offending memorials, while in other cities, protestors took matters into their own hands. In 2020 in Macon, Georgia, where Buchanan lived from 1977 to 1985, the city agreed to move a Confederate soldier memorial that was built on the site of a former slave market, but it was unclear who would be responsible for the costly relocation. Some of the vitality of public and land art is derived from the inherent charge of erecting symbols in public, and Buchanan, a Southern-born, Black American artist, was well aware of the connotations of selecting coastal Georgia as the site of her work.

Situated in the coastal Marshes of Glynn, just 15 minutes from St. Simons Island, where a group of enslaved Igbo people drowned in a mass suicide in 1803, Buchanan’s Marsh Ruins processes centuries of local history. Dozens of individuals walked, in chains, away from their captors into Dunbar Creek. Buchanan’s work wears its historical inheritance lightly. How better to commemorate the lives of people who resisted captivity in a self-sacrificing and non-violent way than to erect a subtle memorial to them that will corrode over time? The formal qualities of Buchanan’s mounds, from their crumbling materials to their low position among the tall grasses that obscure them, situate them within a broader context of land art and reveal a concern with the relationship between art and ecology.

Buchanan’s work wears its historical inheritance lightly.

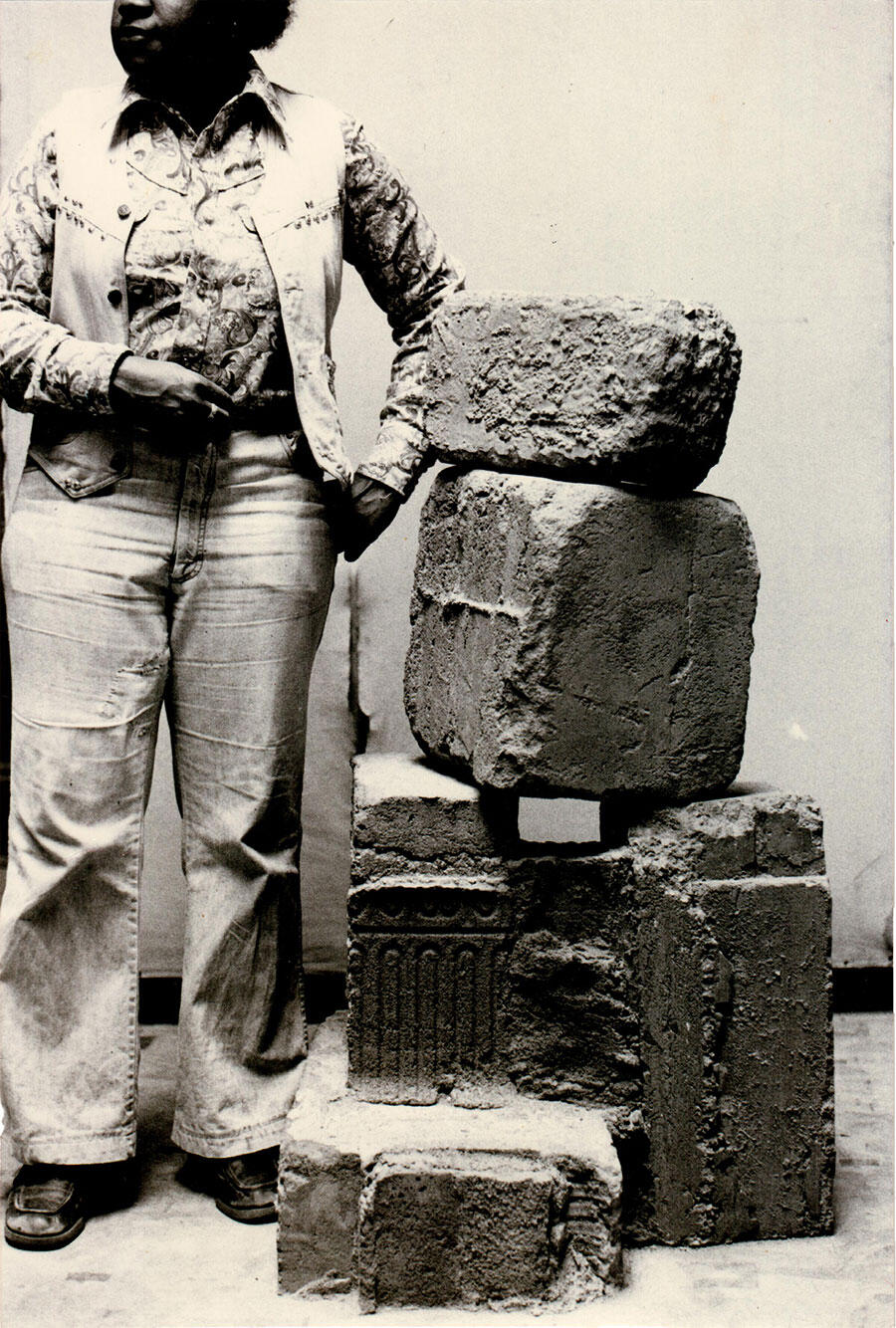

The preservation of works of land art is also dependent on how the public decides to treat them. Marsh Ruins has stewards in the form of museum professionals and gallerists, but it is also at the mercy of those who visit it. In a 2016 article in Rhizomes, writer Andy Campbell recounts an occasion when Buchanan drove by her outdoor sculpture Unity Stones (1983), installed on the grounds of the Booker T. Washington Community Center, which serves Macon’s majority Black and working class residents. The stones were built not only to be viewed at a distance, but to be sat on and gathered around, yet when Buchanan passed by and saw three men arguing while sitting on them, she is said to have thought, ‘We’re going to see blood on them next.’ It’s a rich anecdote not only because of the contrast between the men’s tense interaction and the title of the piece, but also because it reveals a recognition on Buchanan’s part of the myriad potential responses that await an artist when they place an artwork in a communal space, rather than a white cube.

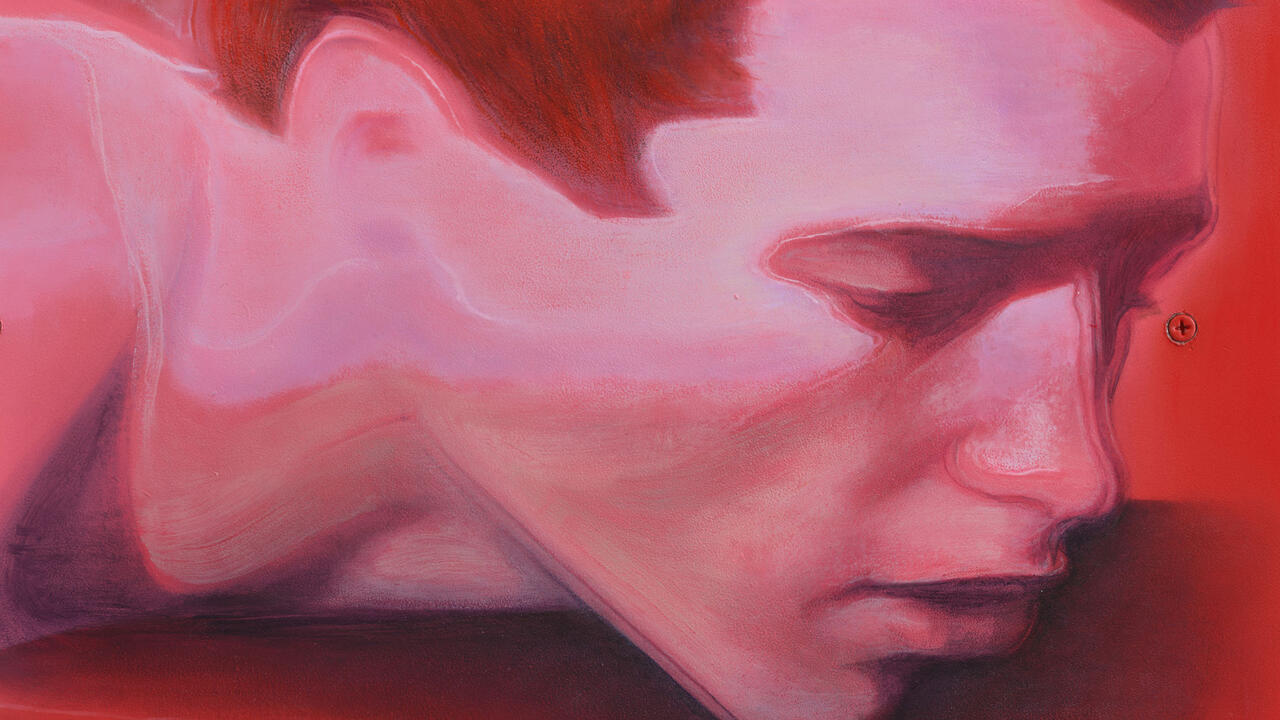

Buchanan’s work and life became important to me as I wrote my first novel, Lonely Crowds (2025). Set in the New York art world of the 1990s, it explores the various sociocultural shifts that gave rise to questions about the role of identity in art that we are still struggling to answer today. For example, is it exploitative to make and sell work about one’s race in moments of heightened visibility and demand prompted by instances of violence done to members of the group, as was the case with the recent boom in Black figurative art that responded implicitly and explicitly to police brutality in the US? Or does art suffer when the identity of the artist is foregrounded in its contextualization and marketing? Buchanan’s work offered a meaningful response to these ethical questions because of the ways she lived in contrast to what American culture insists is aspirational, particularly for those who want to become major artists. Rather than pursuing fame and a highly visible life in a cosmopolitan city such as New York or Los Angeles, Buchanan opted to live in Georgia. Her work also references her identity and self in an oblique way that I found instructive.

My novel makes an allusion to a self-taught Southern artist whose fictionalized gallery show is based in part on Buchanan’s ‘shacks’ and her biography more generally. The protagonist of my novel, Ruth, who has misgivings about her burgeoning success as a Black figurative painter, ventures to the Upper East Side to see the solo exhibition of a Mississippi-born artist who is plucked out of obscurity on his deathbed. The exhibition is advertised as ‘the discovery of an unknown genius from the outside world’, an idea that is a solace for Ruth, who feels ambivalent about the prospect of prosperity or visibility that is tied to the identitarian appetites she perceives in the art world at that time, even as she is desperate to become well-regarded as an artist. Though Buchanan did not work entirely outside the gallery system and was mentored by artists like Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis, the reference is intended to represent a contrast between the protagonists of my novel, who are upwardly mobile, careerist, young Black women artists who want to make a name for themselves, and someone like Buchanan, whose work derives its power, in my mind, not only from its elegance and simplicity but also from its self-effacing quality and the acceptance of its own gradual dissolution. Buchanan’s work suggests a potentially more enlightened relationship to one’s career, belongings and, even, oneself – since all of this will be erased in time.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Fall into Ruin’

Stephanie Wambugu’s ‘Lonely Crowds’ is published by Little, Brown and Company

Beverly Buchanan’s ‘Weathering’ is on view at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, until 1 January and will travel to Frac Lorraine, Metz (27 February – 26 August) and Spike Island, Bristol (26 September – 10 January 2027)

Main image: Beverly Buchanan, installation of Unity Stones (detail), c. 1983, artist’s book. Courtesy: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C