Pitupong Chaowakul’s Novel Architecture Anticipates Decay

With his Bangkok-based studio, Supermachine, the designer proposes buildings to bend, weather and endure, imagining a city shaped by survival

With his Bangkok-based studio, Supermachine, the designer proposes buildings to bend, weather and endure, imagining a city shaped by survival

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 256, ‘The Shape of Shape’

In Pitupong Chaowakul’s 2018 commission by the Association of Siamese Architects for the Venice Architecture Biennale, the architect and artist suggested something unusual: that he ‘restore’ Bangkok’s flooded, largely destroyed New World Mall while maintaining the building’s ruinous structure. Chaowakul’s proposal – which incorporated the large, fish-filled pond that had formed on the shopping centre’s ground level – still featured signatures of his own style and that of his studio, Supermachine, like its open-air, permeable design with visible scaffolding and armature. But where common approaches to natural disaster and climate change understandably prioritize solidity and permanence over the porous and the temporary, Chaowakul’s novel architecture anticipates, and even pre-empts, its own decay and potential destruction. This flexible mode necessitates a bottom-up revision to a building’s form, where a malleable and inventive approach to shape and line succeeds over the weight and rigidity of conventional frame and volume.

After the 2014 Mae Lao earthquake in Chiang Rai, Thailand, Chaowakul and Supermachine rebuilt a destroyed wooden school- house to better withstand future seismic activity. The results showcase the architect’s emphasis on the natural curves and forms of materials normally hidden from view. The design features a rounded, L-shaped pavilion composed of square thatch panels and an open gazebo – sheltering two classrooms – propped up with abundant, tree-like bamboo supports. Modern Western construction commonly relies on metal or wood armatures surrounded by insulation and opaque outer shells of plaster or concrete – dense exteriors that, like those of the former school, can be especially vulnerable to Thailand’s tropical, quake-prone climate. In Chaowakul’s redesign, the school’s breezy arbour disperses an already lightweight roof across replaceable, pliable bamboo, allowing greater resilience – and easy mending – down the line.

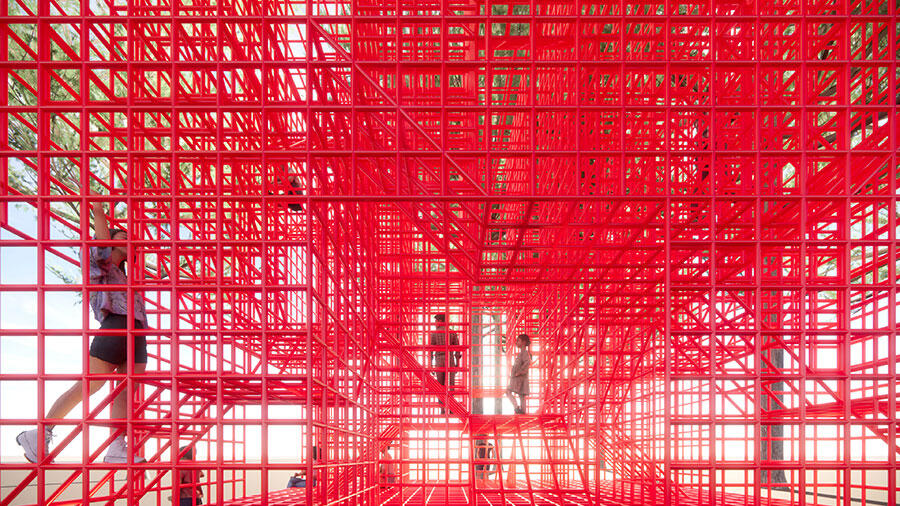

Chaowakul’s layouts for roofs and walls usually condense framing, insulation and siding into a single layer – a strategy that deconstructs solid volumes into their segmented, flattened shapes. The results feel close to a kind of drawing, as though Chaowakul and his collaborators were pencilling their structures into space – an approach that is especially visible in the architect’s temporary art installations. The See San Doitung Tunnel (2016), for example, was a 40-metre arched entryway to an eponymous local festival that featured handmade rectangular quilts, stretched and anchored to a set of thin, curved bamboo rods using simple string knots. The partially see-through passage – the sky was visible through gaps between quilts – turned a would-be opaque structure into an airy matrix of sticks and squares. At Khao Yai’s Big Mountain Music Festival, where Chaowakul has been artistic director, Supermachine regularly constructs similarly colourful canopies of quilt-like sheets buttressed by simple bamboo stands, providing shade without eliminating airflow or views.

Though other projects – particularly luxury ones – necessitate more durable materials, Chaowakul manages to transform conventional facades into amorphous, permeable frontage. Supermachine’s 2022 proposal for a New Station Hotel in Bangkok includes an adjustable exterior ‘skin’ crafted from ridged panels of varying sizes. Like the Doitung Tunnel, the hotel’s walls are sinuous and membrane-like, with hints of a bright interior peeking through the spaces around each four-sided segment. The structure’s integrated armature and siding form one moving apparatus; digital renderings showcase thin metal rods lifting portions of the facade, as though the bubble-like, ovular building were inhaling and exhaling. The curved, bodily shape of the hotel recalls Chaowakul’s 2012 collaboration with Wattikon Kosolkit and Yupadee Sutvisith on a proposed ‘Future House’, a dramatic, spiralling, half-cylinder home – reminiscent of an elbow and bent arm – largely elevated from the ground. Here, the corporeal impression conveyed by many of Chaowakul’s designs was made surprisingly literal. Overlapping, pangolin-inspired ‘scales’ gird the residence: water-repellent, movable plates that would enable the building to flood with minimal damage.

‘Bangkok Bastards’ is Thai architect Chatpong Chuenrudeemol’s affectionate term for the makeshift, hybrid shelters that have become permanent fixtures of the city’s unique skyline. While Chaowakul’s work is hardly ad hoc, his ‘soft architecture’ – a phrase that describes changeable and porous, as opposed to static and enclosed, buildings – embodies the dynamism and sensuality of Chuenrudeemol’s words. His completed structures have the strangely intimate quality of a sketched figure study, their lines, cones and cubes stretching towards something new. These ‘bastards’ are liberated from more restrictive legacies – and are better prepared for the future as a result.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Adaptable Architecture’

Pitupong Chaowakul is part of the Thailand Biennale Phuket 2025, until 30 April

Main image: 10 Cal Tower, The Labyrinth #1 (detail), 2014, Cholburi, Thailand. Courtesy: Supermachine Studio; photograph: W workspace