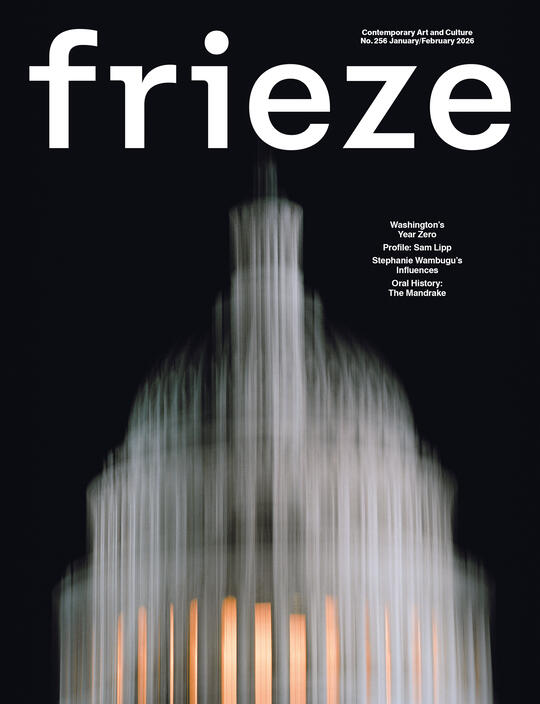

Can Washington DC’s Cultural Institutions Survive Trump?

As the President reshapes the nation’s capital, the city’s arts community struggles to withstand an administration obsessed with the arts

As the President reshapes the nation’s capital, the city’s arts community struggles to withstand an administration obsessed with the arts

Towards the end of Joe Biden's presidency in 2024, I found myself at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, walking a majestic balcony cantilevered over the Potomac, the monumental city lighted by the sunset. Despite periodic additions, the performing arts venue retains much of its mid-century charm: all open promenades and functional geometries and people milling about in slightly rumpled evening attire. During my 25 years in DC, this place has always felt like it captured a genius loci, a permanent embassy dinner energy – some Cold War panache there, yes, but buttoned up, a bit of a snooze. That’s not to say the performers aren’t always top-flight. It’s that, like most things in this town, the programmers aimed for a middle-brow consensus: family-friendly Americana, better-known operas, or a twist of Broadway.

This evening was a variation on the theme. Jason Moran, who had been artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center since 2011, played a suite of Duke Ellington songs. Apt, because Ellington was born in DC, long a lively Black city interspersed with dreary federal edifices. His standards are timeless, part of the national patrimony. Moran, an avant-garde composer and daring visual artist, set himself to breathing a contemporary energy into the music. Surrounded by the hundreds gathered, I was rapt by the pianist’s mournful virtuosity and the fresh resonance of those notes. It was the sort of show that made one grateful that the Kennedy Center quietly carried on night after night, year after year. Like the Smithsonian Institution (SI), of which it is a bureau, the sense of inevitable skilfulness there was easy to take for granted.

The anxiety in DC is palpable – and new.

Talking to Moran a few months later, he noted that in moments of turmoil he would turn to a piece like Ellington’s 1953 ‘Melancholia’ as a balm. It was a timely recommendation for 2024, when a world already on fire, both actually and figuratively, was about to become more sombre still. That DC predictability would be lashed by wave after wave of upheaval: election season, a new administration, DOGE’s young hackers chainsawing through the federal workforce, constitutional challenges, troops in the streets. As of last summer, Moran is no longer at the Kennedy Center, having resigned on 19 June 2025 – Juneteenth – in the wake of the White House dismissing Democratic appointees from its board and current president Donald Trump himself taking control as chair: an unprecedented manoeuvre.

There have been many such firings, resignations and ‘retirements’ of late, including Kim Sajet (director of the SI’s National Portrait Gallery since 2013), Carla Hayden (librarian of Congress since 2016) and Colleen Shogan (archivist of the United States since 2023). The legality of such ousters appears ambiguous. But while the top tier of leadership in DC arts institutions churns with every incoming administration, the bureaucrats who run those places typically carry out their work in a dispassionate way, guided by a wonky single-mindedness rather than partisan zeal.

To witness the thousands of tourists shuffling between museums on the National Mall is to remember that the Smithsonian is a line of contact where the US flexes its scientific credibility, shows off its artistic sophistication and celebrates a certain vision of civic religion. The new administration seems to understand this PR function on a visceral level, but, unlike Trump 1.0, it also knows that for every gallery on Independence Avenue, there are countless other offices and warehouses where research is under way, symposia held, performances staged and curatorial decisions made. US governmental agencies have always been led by hacks; this time, those hacks might meddle in the unglamorous acreage where things actually get done. If this sort of activism is one source of the anxiety coursing through the DC arts establishment, another is that the pursuit of ‘facts’ is now understood to be ideological rather than apolitical. That knowledge and power cannot be untangled is an old insight of the left, but one newly jarring as the secretary of state, Marco Rubio, takes the helm of the place where the presidential records and the Declaration of Independence are housed, and when Lindsey Halligan, a former insurance attorney loyal to the president, was (briefly) brought on to ‘restore truth’ and remove ‘improper ideology’ from the SI’s museums, per an executive order of 27 March 2025. What that looks like in practice remains, at the time of writing, unclear.

That executive order explicitly took aim at what it calls the ‘corrosive ideology’ of ‘rewrit[ing] history’ to promote ‘national shame’ – that is, efforts to re-centre aspects of American history and creative practice that include its darker chapters, such as enslavement or Indigenous extermination policies. In this view, a more holistic presentation of America’s complex and cosmopolitan texture amounts to radical revisionism, to be counterbalanced by a pendulum swing in the direction of triumphalist pageantry (such as the slated ‘National Garden of American Heroes’, whose 250 statues would pay homage to an eclectic – if surprisingly inclusive – cohort, from Harriet Tubman to John Wayne). This traditionalist bent is of a piece with the reactionary tenor of the firings themselves: many leaders throughout the government (including Hayden) are Black; others promoted Black, Asian, Indigenous and women artists in their programming. Sajet, for one, presided over the commissioning and unveiling of Barack and Michelle Obama’s official portraits, by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively.

Those portraits, of Black people by Black artists, seemed to augur a curatorial shift at the NPG and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), with which it shares a building. The latter’s recent reinstallation of its contemporary collections features exceptional works by Mark Bradford, Nam June Paik, Fritz Scholder and Mickalene Thomas. The rehang brought SAAM into alignment with larger shifts in the mainstream art world while telling a more capacious and artistically virtuosic story of American art. Two of the finest group shows I encountered anywhere in recent years were at SAAM: ‘¡Printing the Revolution!’ (2020, 2021), a collection of Chicano agricultural protest posters, and ‘Pictures of Belonging’ (2024–25), which gathered portraits by three Japanese American women artists who lived through the period of wartime internment between 1942 and 1946. Both contexts produced strikingly original American art but were of little use to a nationalistic perspective.

It was difficult to research this essay, much less to get anyone to agree to be quoted. As I write, the federal government has been shut down for several weeks, the SI’s doors locked tight and my colleagues furloughed. Conversations I had scheduled are deferred indefinitely; those who will talk to me do so off the record, fearing for their livelihood. The anxiety in DC is palpable – and new.

It is not that art workers in DC are unfamiliar with political interference, it’s that this crisis seems more diffuse and amorphous.

While shutdowns are an all-too-commonplace feature of government work, until this year they tended to be viewed like a blizzard: something that will blow through while you hunker down at home. This time, it is rumoured that there will be no back pay, just lost wages. Mass layoffs across agencies seem to be underway (though temporarily blocked by a court). While some are sounding the alarm that ideological checks on our museums will look like a repeat of the 1980s (think Robert Mapplethorpe at the Corcoran), the shutdown firings suggest something more subtle: that institutions will slowly be corroded. A large section of SAAM will close for refurbishment this spring. This is standard procedure, true, but what objects will move? Will wall texts be altered? What future installations will now not happen?

And who will be the wiser, or paying attention a year or more hence? There’s an attentional dimension to the current administration’s tactics – one cannot keep up with the news cycle – but also a certain mafioso playbook in action. If one’s high-profile peers are made examples of, one begins to comply without direct coercion; no one wants to speak up. So when a much-touted retrospective of an important Indigenous artist is suddenly delayed by over a year, and my routine queries are answered only in oblique bromides, I am left nonplussed: is this business as usual, or is it censorship in all but name?

It is not that art workers in DC are unfamiliar with political interference, it’s that this crisis seems more diffuse and more amorphous. The 1990s, for instance, saw contemporary art pilloried during the congressional hearings for the (comparatively paltry) National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities grants on the grounds of ‘indecency’. Back in 2010, ‘Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture’ at the NPG drew the ire of religious groups for its inclusion of a truncated David Wojnarowicz film that briefly depicted ants scurrying on a cross (A Fire in My Belly, 1986–87). After a week of protest and counterprotest, Smithsonian management removed the film from view on 1 December – World AIDS Day – while issuing a statement in support of the group show.

The affair felt, at the time, like a reactionary redux – another instance of Washington being out of touch. During the ensuing years, the removal of the Wojnarowicz film even began to seem like a last gasp of the ancien régime. A new generation of curators and voters was coming up, Obama was in the White House, and DC itself was becoming, if not hip, then more like a cousin of Brooklyn or Hackney. In short, it seemed like progressives were winning, even in the once stodgy federal city: at his inauguration in 2021, Biden was presented with Robert Duncanson’s painting Landscape with Rainbow (1859) – a first for a Black artist – on loan from SAAM; Mark Bradford’s epic Civil War painting Pickett’s Charge (2017) at the Hirshhorn Museum was becoming a semi-permanent pilgrimage site; and the National Gallery of Art mounted a major exhibition of 50 Indigenous artists curated by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (‘The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans’, 2024), as well as shows on Haitian modernism (‘Spirit & Strength: Modern Art From Haiti’, 2024–25) and the Black arts movement (‘Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985’, 2025–26).

At the same time, the ‘Hide/Seek’ controversy had been addressed by the Smithsonian’s leadership with a memo awash in bureaucratic dissimulation but clear on its affirmation of the institution’s own Directive 603, which stipulated oversight of ‘controversial shows’ involving ‘issues on which curators, scholars, or segments of the public may disagree on substantive grounds as to the presentation or contents of an exhibition’. It is this ambiguous directive, dating from 2003, that many fear may be used as a kind of purity test to reverse the curatorial sea change of the post-Obama years. But this remains to be seen. The one show that everyone acknowledges was ‘cancelled’ is Sherald’s ‘American Sublime’ in July 2025. Set to run at the NPG, it opened instead an hour away at the Baltimore Museum of Art. But, as has been widely reported, it was Sherald who withdrew, after the Smithsonian leadership proposed to include a didactic video alongside her Trans Forming Liberty (2024), a grisaille rendering of a national icon with a vibrant pink coif. While the curatorial motivations and merit here are debatable, the fact remains that it was the artist’s choice to cede the platform.

While Sherald’s case got all the press last summer, at the same moment, the SI’s Anacostia Community Museum – founded in the city’s poorest area in the wake of the civil rights movement – was quietly defunded, losing 60 percent of its budget and 17 federal employees. Its celebrated director, Melanie Adams, was moved to another position and will not comment on the situation there; the new interim director, Katelynd Anderson, could not speak due to the shutdown. The emerging consensus here is that the 60-year-old site will wither on the vine while attention is diverted elsewhere.

The pursuit of facts is now understood to be ideological.

For now, the curatorial class in DC remains on edge, working (or not) from home, hoping exhibitions organized over the course of years will open as planned. Outlandish episodes make the water-cooler rounds: a scuffle about moving the remnants of the space shuttle Discovery from the National Air and Space Museum to Texas, or the deposition of Todd Arrington, director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library, for failing to deaccession a sabre so that Trump might gift it to King Charles. Rumours about an unorthodox Venice Biennale selection process were suggested to be resolved in November with the apparent selection of sculptor Alma Allen – a choice that struck most as, in a word, bizarre.

During Trump 1.0, the breaks from local norms seemed a matter of degree, not kind; a playing out of old conflicts. The DC consensus had always been that culture wars jousting was fair play out in the hinterlands, but once inside the Beltway, it was okay to dust off one’s tux, take in a show at the Kennedy Center and let the experts do their thing – even if this meant DC culture was out of step with an imagined populist sentiment out there in the interior. No longer. As you read this, the longest shutdown in history will probably be over, but not without having pushed millions into food insecurity in November. Meanwhile, the administration hosted a Great Gatsby-themed party in south Florida, whilst planning a triumphal arch near the storied Lincoln Memorial. In October, the East Wing of the White House stood intact, as it had since the days of Teddy Roosevelt; now it is rubble. Anything seems possible. For now, the administration is probing to see if institutions will walk away, capitulating in advance to avoid a public fight. Barring that, all the pieces are in place for a heretofore unseen phase of pressure on curators. DC will never be the gallery town that New York or London is, but it has the bully pulpit of its national museums. It used to be the business of progressives to critique the slow-footed consensus-building of these places, but you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Scare Tactics’

Main image: US National Guard troops patrol the National Mall in Washington (detail), DC, 2025. Image commissioned by frieze. Photograph: Nate Langston Palmer