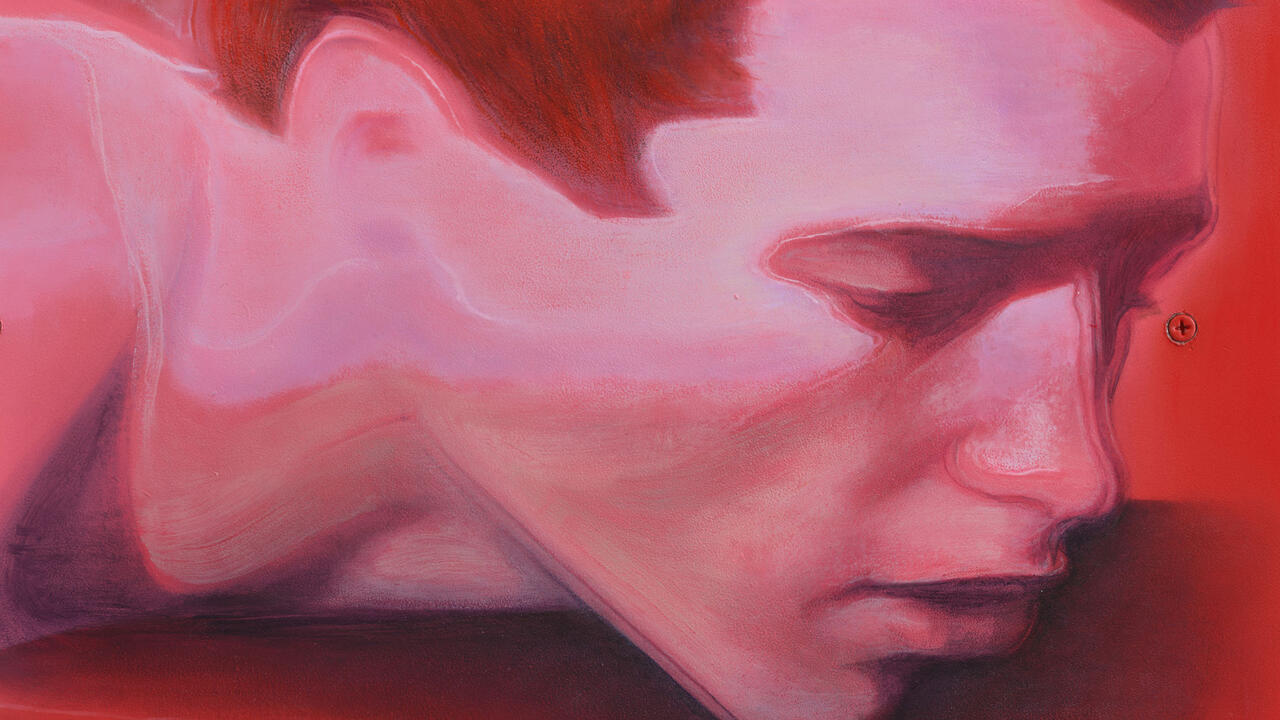

Carol Bove’s Fifth Avenue Era

The influential sculptor, whose mammoth works adorned the Met’s façade, reflects on the spiritual blind spots and esoteric histories behind her nearby Guggenheim show

The influential sculptor, whose mammoth works adorned the Met’s façade, reflects on the spiritual blind spots and esoteric histories behind her nearby Guggenheim show

Carol Bove You know how there’s something wrong with culture and with society right now?

Ariana Reines I have no idea what you’re talking about [laughter].

CB I’ve been thinking a lot about it – like everybody has – and it has led me to think about ancient history and into sense perceptions that only subtly register. One of the most basic elements of the problem is this: when you privilege your mind over your body, you no longer empathize with yourself, and when you stop empathizing with yourself then you stop empathizing with everyone and everything around you. This is what makes exploitation possible. Exploitation isn’t possible until you stop empathizing with yourself. There are so many ways in which museums reinforce this rejection of our bodies – our experience of art through our bodies. I’m trying to figure out a way to undo this very basic and pervasive condition.

One thing I’ve noticed in museums is the insufficient seating. The implicit message of no seating is a rejection of your human body and its needs. Your body is not invited into the space. This is a profoundly hostile message. And the hostility is conveyed in other ways – the full message can be translated into something like, ‘we’re grudgingly accepting that you have a body that carries your mind around, but we wish it weren’t so.’ There are so many ways that museums make people feel they’re not invited. Don’t touch anything, actually just keep walking and don’t take your time. Don’t feel comfortable. The messaging rein- forces the cultural programming that separates us from the world. To do rather than to be. Don’t just sit there.

AR I was thinking about the connection between The séances aren’t helping, your Facade Commission at the Metropolitan Museum of Art [2021], and your upcoming exhibition at yet another iconic New York landmark – but with a totally different DNA and character – the Guggenheim. You’re moving from the facade to the core.

CB Also, both are on Fifth Avenue.

AR Yes, you should just own all of Fifth Avenue [laughter].

CB I moved to Fifth Avenue right after the Met commission. And I’m going to move out right when the exhibition opens, so this is my Fifth Avenue …

AR … era?

CB Yes, weirdly. There’s this Shirley Temple song, ‘Fifth Avenue’ [1940]. I used to watch Shirley Temple when I was a kid, so it’s been in my head for years. I’m going to exorcise this song with this show. It’s going to go.

I’ve had some trepidation about doing a retrospective because it sounds so final. And it is in a way – after considering everything that came before and then presenting it as a single idea, my work and I will be changed. The show will be very traditional in some ways. We’re arranging the 25 years of work in chronological order. We’re planning a lot of surprises, though.

That’s the starting point for me: the negative space.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how programming could mean just serving tea and making people comfortable. With the show I did at the Museum of Art and History in Geneva last year [‘La Genevoise: Carte blanche à Carol Bove’, 2025] …

AR … Oh yes, I watched the videos on YouTube with you in conversation with the museum director, Marc-Olivier Wahler. You pointed out how deeply uncomfortable people are in museums, and how in the gift shop they relax because they can touch things, but then we shit on that and say it’s evil capitalism. But what if art spaces are just rude to people?

CB Commerce isn’t necessarily capitalism.

AR I’ve read that you don’t make drawings or sketches. So how do you build a model – do you improvise?

CB Well, I build a space.

AR And then you improvise inside the space?

CB Yes, it’s very improvisational. When I was doing the Met commission, I built one of the niches here [in the studio] at full scale, and then I would take elements and just hang them in relation to the void. I guess that’s the starting point for me: the negative space. Then I have an overhead crane, and we use forklifts to bring elements into relation with this void. It’s very easy to use.

AR It’s very intimidating to me! [Looks at the crane’s control panel]

CB You get used to it. Try it.

AR [Presses on the ‘DOWN’ button] Oh, that’s very empowering [laughter].

CB I know. You feel it in your body when you lift things with a machine, and somehow it also elevates your mood.

AR I heard you say in conversation with [art historian and curator] Catherine Craft that once objects are over 300 pounds, you have to lift them with machines. This helped me understand the effect of levity and play in your work – how, once you’re lifting with machines, you’re able to make very heavy objects become light or even delicate. I’m fascinated by your transition into working with steel and larger found materials. I’ve read that it wasn’t something you planned, that it maybe came out of being so celebrated for what came before.

CB The shift away from junk assemblage towards high-polish industrial fabrication came more from my boredom with my own taste. I was also disgusted with the tastefulness of my taste and I wanted to open up some new possibilities. I thought to include more questionable taste and humour.

AR So steel was a way to challenge yourself.

CB To make fun of myself. When I got out of school [New York University in 2000], I started this project. In other words, all of an artist’s work can be understood as a single project. An artist can abandon a way of working or go off in a new direction, but she can’t entirely free herself from older work. With this in mind, anytime I’ve pivoted, I’ve intentionally designed in relation to everything I’ve done before.

As an artist, you have to get out of your way in order to get the real transmission.

In the beginning, I was making these drawings and they were really painful. At the time, I felt like the drawings justified their existence because I suffered for them. I would sometimes sneak away from the drawings to arrange objects on shelves and considered this activity a guilty pleasure. And then, after some time, I realized the guilty pleasure was the real work, and the painful process was unnecessary. As an artist, sometimes suffering is necessary, sometimes not; you have to get out of your way in order to get the real transmission. I’m not saying it doesn’t come from me, but in a way, it doesn’t. The work doesn’t serve my needs, I serve its needs. The only really odious part left is maybe the fundraising, the admin and I guess the curating, the caretaking for the Harry Smith materials and related archival projects – actually there’s plenty of suffering [laughter]. But it isn’t the hard work that validates what I’m doing.

AR It seems like he’s a spirit that you’ve taken it upon yourself to take care of since you curated that show at the Whitney [‘Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith’, 2023–24]. He’s such a fascinating, cult figure in American folk music, but also this amazing artist and painter.

CB Yes, but it also feels like it wasn’t a choice. It’s like he recruited me. There’s this question of predestination or free will. These are mysteries in life, right? Determinism and free will are mysterious. How much freedom do you have?

AR That seems like one of the central questions of your work. Your objects have a double- or triple-take effect, where it seems like you’re peeling back layers of conditioning to see if there’s more free will available in your perception.

CB I was reading over the weekend about the seven factors of awakening in Buddhism. And I thought, yes, that’s what I’m trying to do. The first is mindfulness, and the second is investigation of phenomena. The latter is so key for this work, or my approach: I want things to be totally what they are, but for them to also trick or entice you, to hopefully bring more of your perception into the work and your interaction with the phenomenal world.

Normally we’re taking so many mental shortcuts – we have to – and deciding that a lot of sense perceptions are irrelevant. But a physically inscrutable object signals to you to start using more data. Then you’re put into a different frame of mind.

AR I feel like your objects have an uncanny way of pulling the space around them towards themselves or pulling the invisible towards them.

CB Yes. That’s what I’m training to do now: to see the banal. The thing you can’t see because it’s so normal. Things hidden by a normal spell.

AR [Stares at a work titled Level Boss, 2025, mounted on the studio wall] It looks so soft, velvety, almost creamy.

CB I like how that shows up. When you see these objects painted and they’re not finished, when they don’t have that last coat, they don’t look mysterious. It’s just painted metal. But then the matte paint does something: it doesn’t look like metal at all anymore.

AR And you sense that it’s hollow, but you don’t really know; it feels like it could be hollow in one place but not the other.

CB Yes: why is it acting like that? I also sense that it could be a mirage. And we’ve looked at so much digital media, and it also reminds us of that. The sculptures – maybe not this one, but others like it – go into a vertical press to get that crumpled look. One thing I’ve noticed when we’re compressing objects is that an onlooker in the studio will say, ‘It looks like a computer model.’ And I’m like, ‘No, this is the thing that a computer model would refer to.’

AR So people perceive these objects as though they’re digital but somehow appearing physically in space. Could that weird blind spot be related to the phenomenon on 9/11 in New York, when everyone was saying it was like a movie, even though those of us who were actually in the city could see everything happening literally in front of us? Is the blind spot always in plain view, but we can’t see it? Is that where the most ideology is somehow pooling?

CB I think so, because with a blind spot you’re saying, this is absolutely inconsistent with my understanding of reality – to the point where you can’t see it. It’s part of a group hypnosis about consensus reality.

AR There’s something very New York about this ocular tuning-out: not knowing how to see what you’re seeing or not being able to tolerate so much density or emotional overwhelm. Self-generated holes in perception.

CB I noticed a headline earlier in the year in The Economist. It was ‘New York is Turning 400 and No One Cares.’ And it’s true. I’m obsessed with history, in a way, and yet I don’t care that New York is turning 400. It’s not relevant to the spirit of this place.

AR I feel like there’s a mystical element to the Guggenheim. But why do I think that? Is it because of the spiral? Because of Kandinsky? Theosophy?

CB Well, Hilla Rebay, who was its first director, was a theosophist. She was a real card-carrying Kandinsky-ite. She was passing out his book Point and Line to Plane [1926] and getting people to subscribe to its dogma. And she commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the building, so it has this theosophical DNA. That’s why you sense it; it’s there.

The topmost part of the building-as-Inferno – that’s where the virtuous pagans and sluts are.

Frank Lloyd Wright was 33 when Queen Victoria died. He’s not a regular modernist. He’s from a different time; he’s a total Victorian. I think that’s really important to keep in mind with the Guggenheim. You can see it if you look at the Oculus. But there’s another layer. Frank Lloyd Wright’s third wife [Olgivanna Lloyd Wright] was a Gurdjieffian. She had been a follower of [mystic and spiritual teacher] G.I. Gurdjieff for six or seven years in Russia and France, and then [in 1932] started with Wright the Taliesin Fellowship [a holistic community that provided architectural training to its members]. She had experience running a cult [laughter].

Moving through the Guggenheim, you go through a process of enlightenment: you pass from gross to fine and from darkness to light. Have you ever seen Botticelli’s illustrations of Dante’s Inferno? It looks like the Guggenheim. The topmost part of the building-as-Inferno – the sixth ramp and skylight – that’s where the virtuous pagans and sluts are. That’s where the exhibition ends.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256

Main image: Carol Bove, The seances aren't helping I (detail), 2021, stainless steel and aluminium, 5 × 2 × 3 m, installation view, ‘The Facade Commission: Carol Bove, The séances aren't helping’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2021. Courtesy: © Carol Bove Studio LLC; photograph: Jason Schmidt