Sam Lipp Scours the Painted Surface

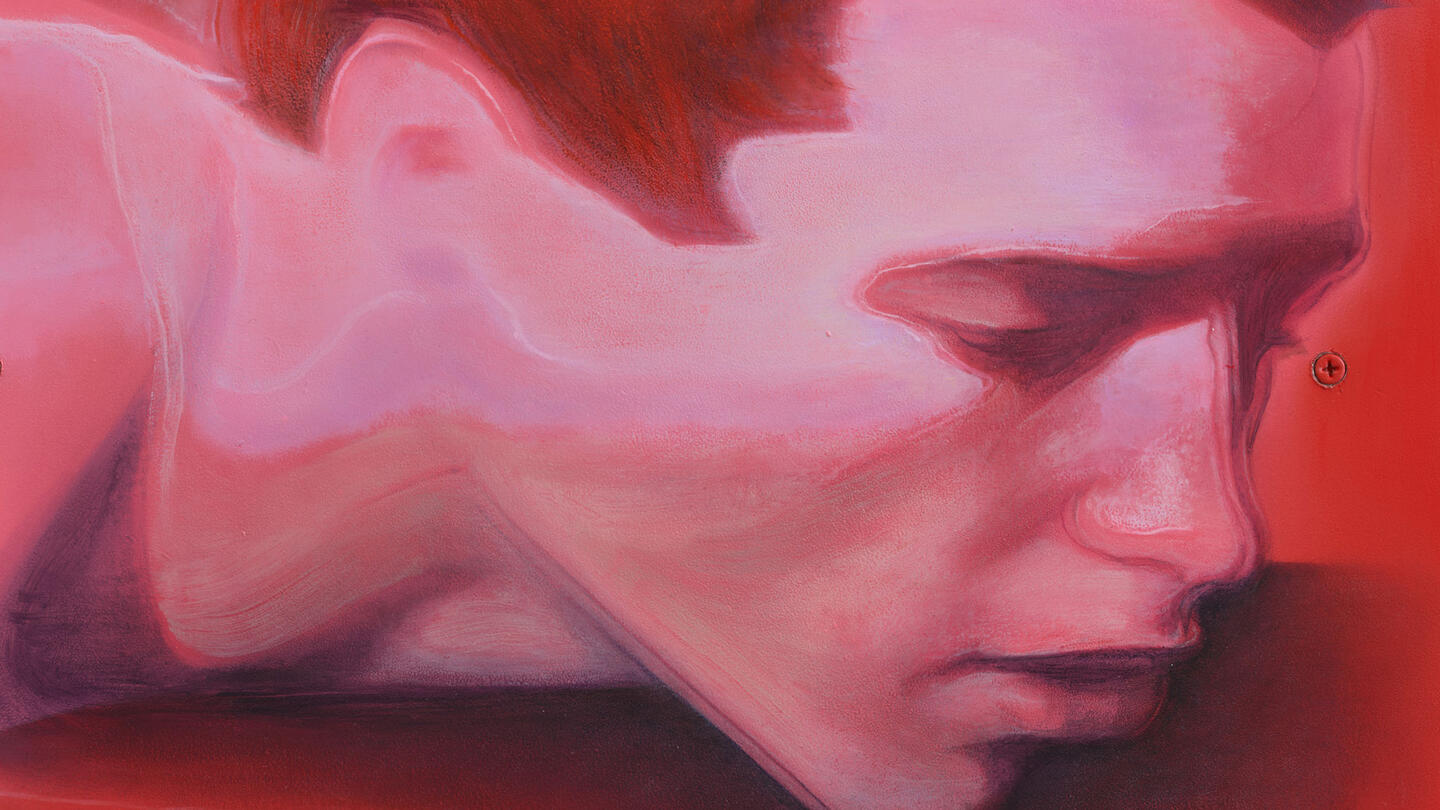

For more than a decade, the artist has rendered flesh, desire and damage into paintings where the image itself becomes the body

For more than a decade, the artist has rendered flesh, desire and damage into paintings where the image itself becomes the body

I meet the painter Sam Lipp in his studio, on the seventh floor of a building in Chinatown, New York. Outside, screeching trains run in both directions across the Manhattan Bridge, concentrating the hum of life in the city into the splitting din of metal on metal. Inside, we talk at length about a new suite of paintings by the artist for his solo exhibition later this month at London’s Soft Opening. Arranged in a tight row like frames in a filmstrip are a series of steel panels, each in a different stage of completion, or maybe transformation. A few are coated with primer; others feature thick strokes of oil paint that have started to resemble faces – one with a cigarette in mouth, another looking breathless, if not faint. The remaining few canvases are undergoing other processes entirely, as if the paint on them has recently been sandblasted off or begun to flake, like the surface of a blister. Four screws fasten each of these panels to the studio walls. ‘My work is about formalizing the condition that positions any one subject in space,’ Lipp tells me. ‘The screws are the condition here. They support the paintings, and so they’re also part of its composition.’

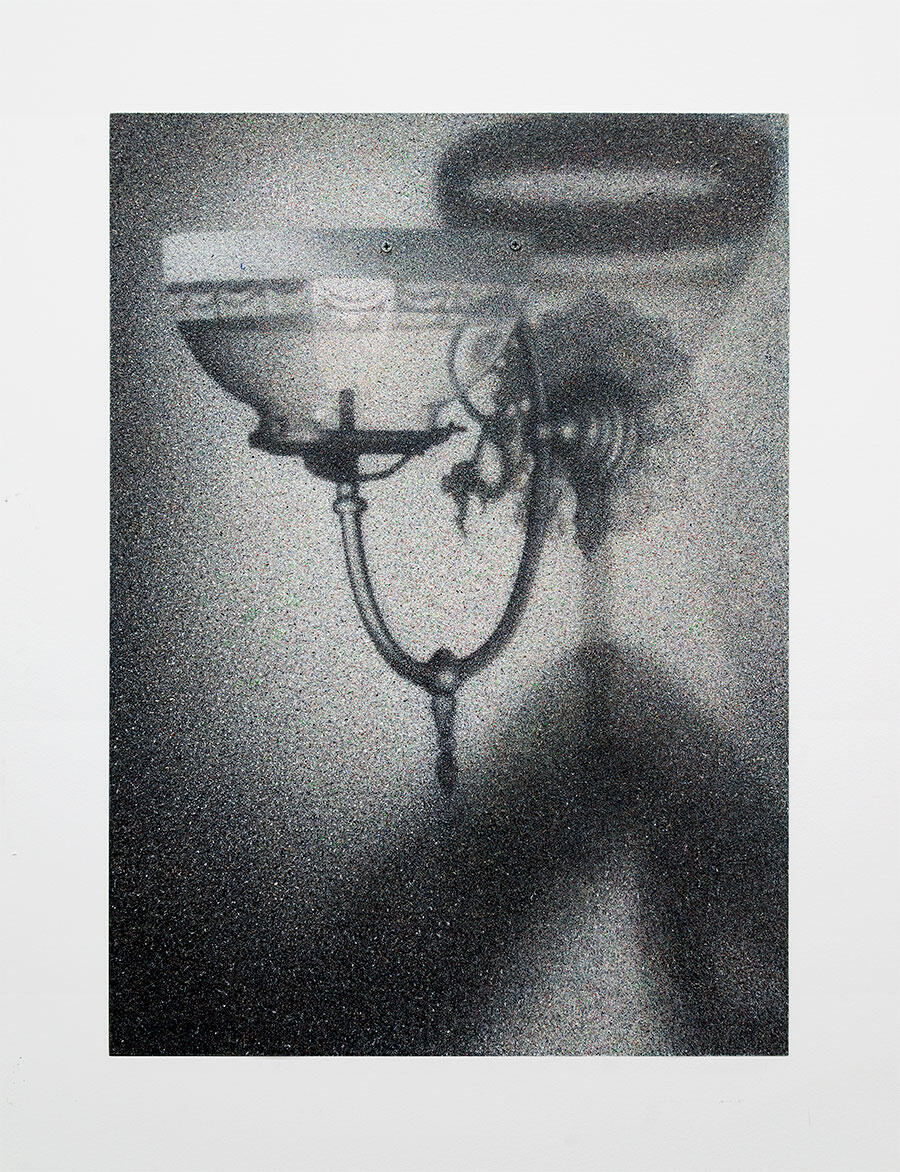

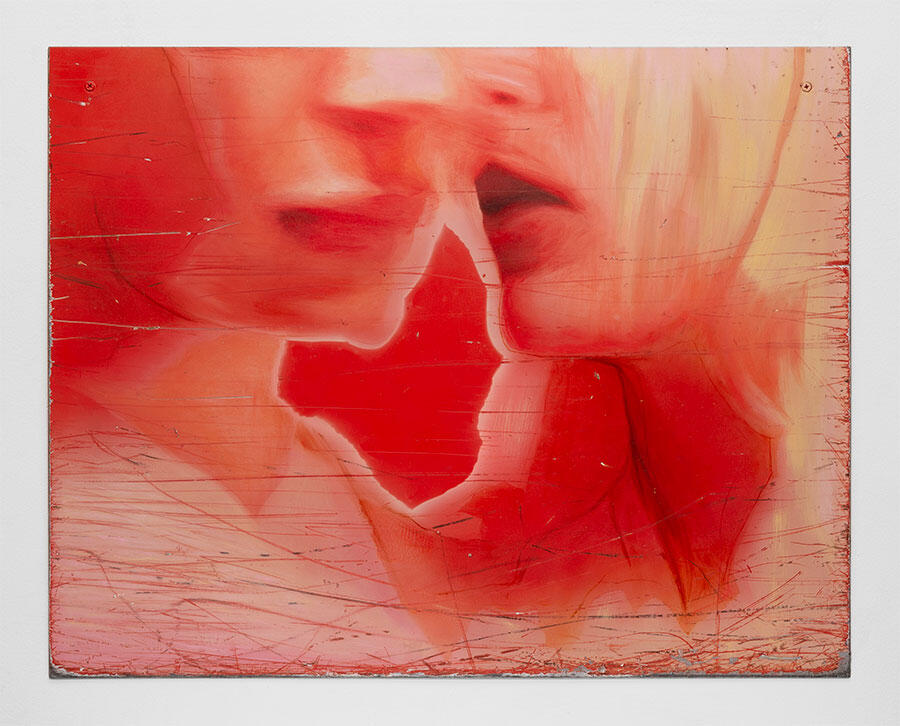

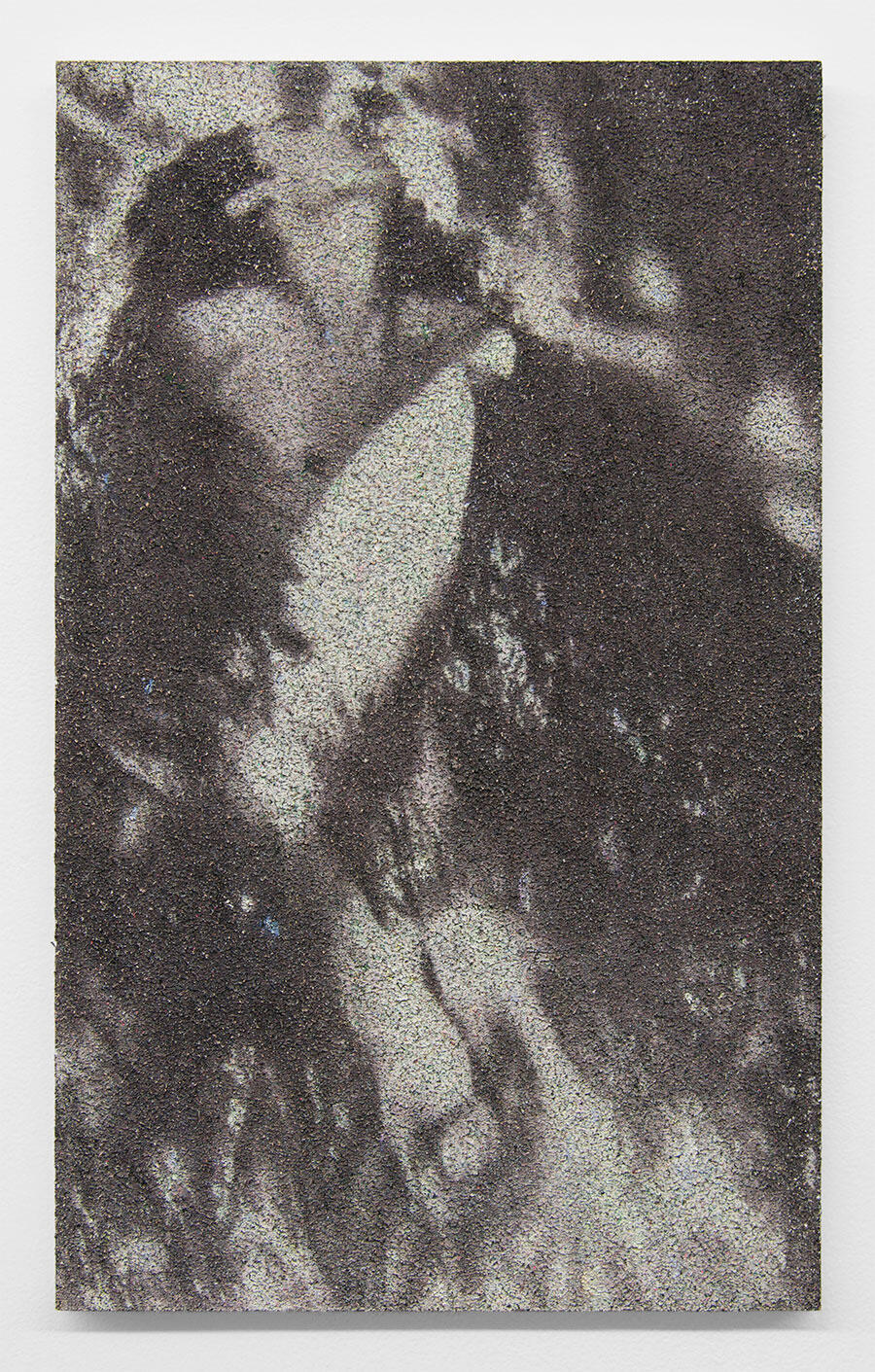

For the last decade, Lipp has used industrial tools and materials to make a body of work that disrupts the gaze with which we experience the effects of both paint and substrate. In works like Sleep (2016), steel wool is used in lieu of a paintbrush on a sheet of foamcore to produce a dense spray of pointillism that mimics the sheen of inkjet printing – its surface looks like it might crumble if touched. In other works, such as New York Doll (2023), tears and scrapes made on the steel backing by dragging it along asphalt complement the lattice of pencil marks with which the artist has drawn a torso. Lipp’s images, which often feature parts of the human body from sources either found or produced himself, fracture their subjects’ cohesiveness, as a glitch does to a display of pixels or as concrete does when it scrapes your knee. ‘I want to represent the experience of being part and parcel of the tyranny of images,’ Lipp remarks of the broken world his images make up, in which flesh is parcelled out as flatness and the figure looks pretty much like the ground.

Lipp talks about his sustained interest in simulating a material debasement of the image, and the precarious materials with which he enacts this fixation. ‘This desire I have for producing things artificially is perhaps an intuitive and honest response to growing up amid the aesthetic milieu of Northern California,’ he says. Lipp, who was born in London but grew up in Napa, remembers how ‘everything around me was painted to look as if it were a villa in Tuscany.’ Using acrylic and watercolour paint as a child, then later experimenting as a teen with oil, was a memory that came to him easily. This is perhaps because the activity channelled a more complex node of feeling – say, that of a small pleasure suddenly rendered as shame, which we tacitly agreed may have had something to do with his growing up queer. ‘Painting allowed me to be weirdly creative and expressive, and at the same time was something secretive – I could be expressive but simultaneously mortified of the expression.’ An early art teacher who opened her home to a pre-teen Lipp introduced him to calligraphy, 19th-century French drawings and prints and the surrealism of René Magritte. He attributes his interest in using foamcore to his father: ‘It’s what my dad would have my art mounted onto as a kid. It had this informal, colloquial method of presentation that, at the time, I wanted to emulate in my paintings.’

Lipp left California to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied sculpture and experimented with video, only returning to paint at the end of his college years – in part, he recalls, as a response to his instructors’ dismissal of the medium. In the years after graduating in 2012, Lipp co-founded and directed the gallery Queer Thoughts, known as QT, with his then-boyfriend, the artist Luis Miguel Bendaña. The gallery began in the couple’s apartment in Chicago, inside the walk-in closet attached to their bedroom, which had its own entrance onto the street. Before long, they were prompted to ‘bring it to New York’, as he tells me – which they did in 2015. Their Tribeca space, above which Lipp had his own studio, exhibited artists like Puppies Puppies, David Rappeneau, Ser Serpas and Diamond Stingily early in their careers. QT closed in 2023. ‘There was always a finite timeline on the gallery,’ Lipp reflects, ‘I never intended to become an art dealer.’

The effect of these works is less a spark of arousal than an exhaustive reckoning with a sudden sense of loss.

Throughout this time Lipp continued to paint, applying his steel wool technique onto materials such as linen (Cruelty, 2014), paper (Looking, 2015) and foamcore, as in A Cobblestone (2016), in which the skin of a shirtless man’s smooth body becomes a landscape of brittle spackle. ‘Truthfully,’ Lipp confesses, ‘no one wanted to buy those, and you can only do certain things that people say no to for so long.’ In 2018, Lipp made a hard turn away from painting on these soft or cumbersome bases and began painting on salvaged steel, a move that suggests that Lipp’s material motivations are less about the annihilation of the image than the ability of any one image to withstand the temporal effects, both fast and slow, of being in the world. ‘What I’m doing is very specifically painting,’ Lipp insists: ‘Paintings about images that continue to refer outside of themselves’.

In Lipp’s more recent work, the painted images themselves become the substrate for other kinds of mark-making. Lipp uses the word ‘frottage’ to describe the act of tying his paintings to a chain and dragging them across the road. In the context of drawing, the word refers to the technique by which paper is held against a textured surface and marked with a drawing medium to produce an imprint. In the context of sex, it means cock-on-cock foreplay. Both meanings suggest that Lipp views these abrasive treatments less like a punishment and more as a movement necessary for mutual satisfaction. In works such as Superstar (2023), a man’s headless torso is encased by the exposed, ragged borders of the steel support. Lipp’s brushstrokes, which render the figure’s firm pectorals, clenched abs and star tattoos in steak-like shades of white, pink and red, are mottled by the road against which the image was rubbed. It might be tempting to situate Lipp’s paintings, specifically those that source images of men’s bodies from pornography or dating apps like Grindr, as exercises in the nude. But they can also be read as part of a particularly gay figurative canon, though here the sexuality in which they are steeped feels minor in relation to the textures of industrial ruin and rot that Lipp’s canvases so carefully regulate. The effect of these works seems to me less like the spark of arousal and more like an impairment or an exhaustive reckoning with a sudden sense of loss.

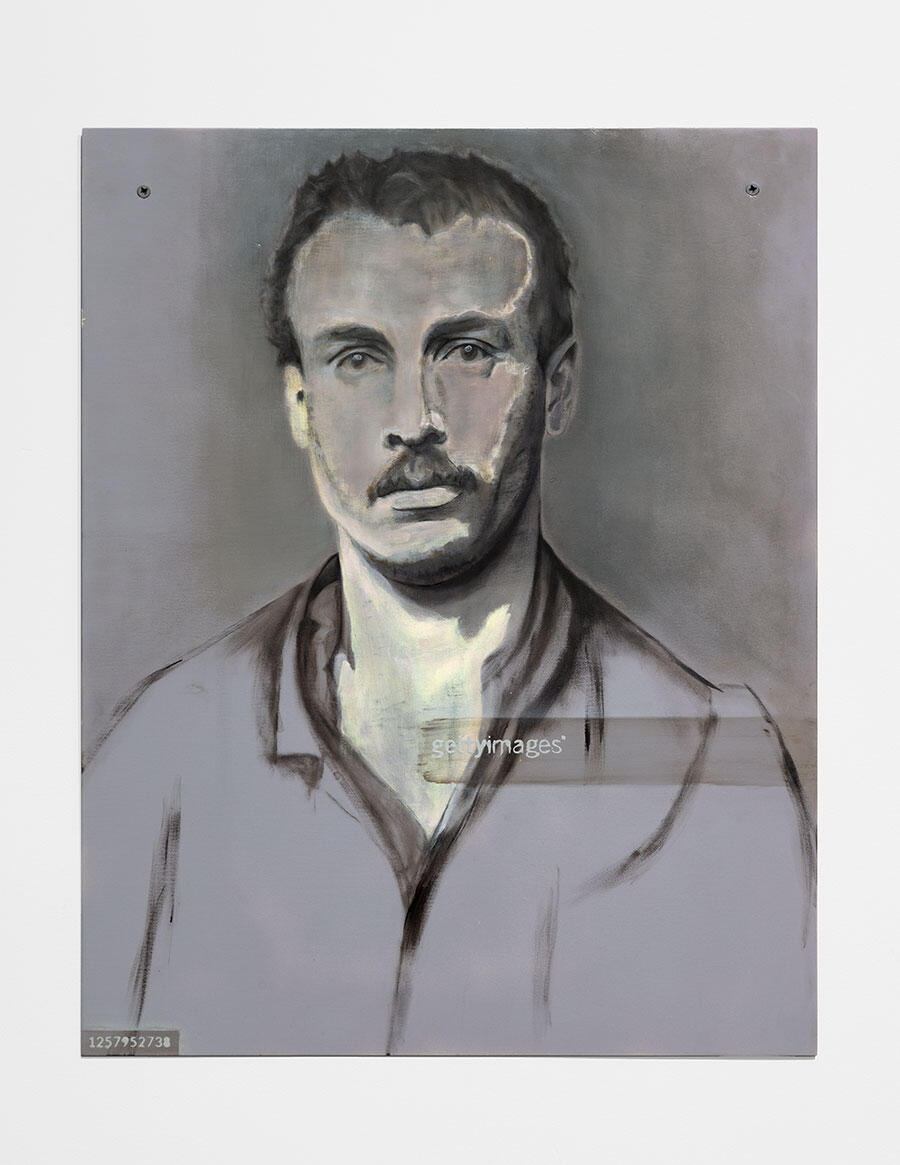

The works that comprised Lipp’s 2019 exhibition ‘Incest’ at Paris’s Bonny Poon gallery, specifically 2746782FH008_jacko_po (2019), clarify this conceptual underpinning of Lipp’s practice. Slightly larger than a sheet of legal paper, the painting, in oil on steel, captures the mugshot image of Michael Jackson – taken in November 2003 by the Santa Barbara County Sheriff ’s Department – after the pop star was arrested on multiple counts for allegedly molesting a child. If you were alive then, you’ll have seen it: Jackson, wearing a pressed white shirt and set against a mute blue backdrop, looks absolutely agog in the face of the camera’s flash. Lipp’s version isn’t sharp. Jackson’s edges are left soft and blurry, because Lipp painted from the cheap rendition of the state-owned original, which had been sold to the commercial archive Getty Images, only to be sold and resold ad infinitum. Naturally, the painting also includes the image bank’s familiar watermark, a dull grey banner that swipes in from the right side of the frame across Jackson’s pursing lips. Lipp’s painting refers not to the pop star or the scandal surrounding him, but to the arbitrary profit margins accumulated by the image as a result of its being deemed public property. ‘I wanted to monumentalize that image somehow,’ Lipp says of Jackson’s mugshot; ‘everything inside that image is about the circumstances that created it.’

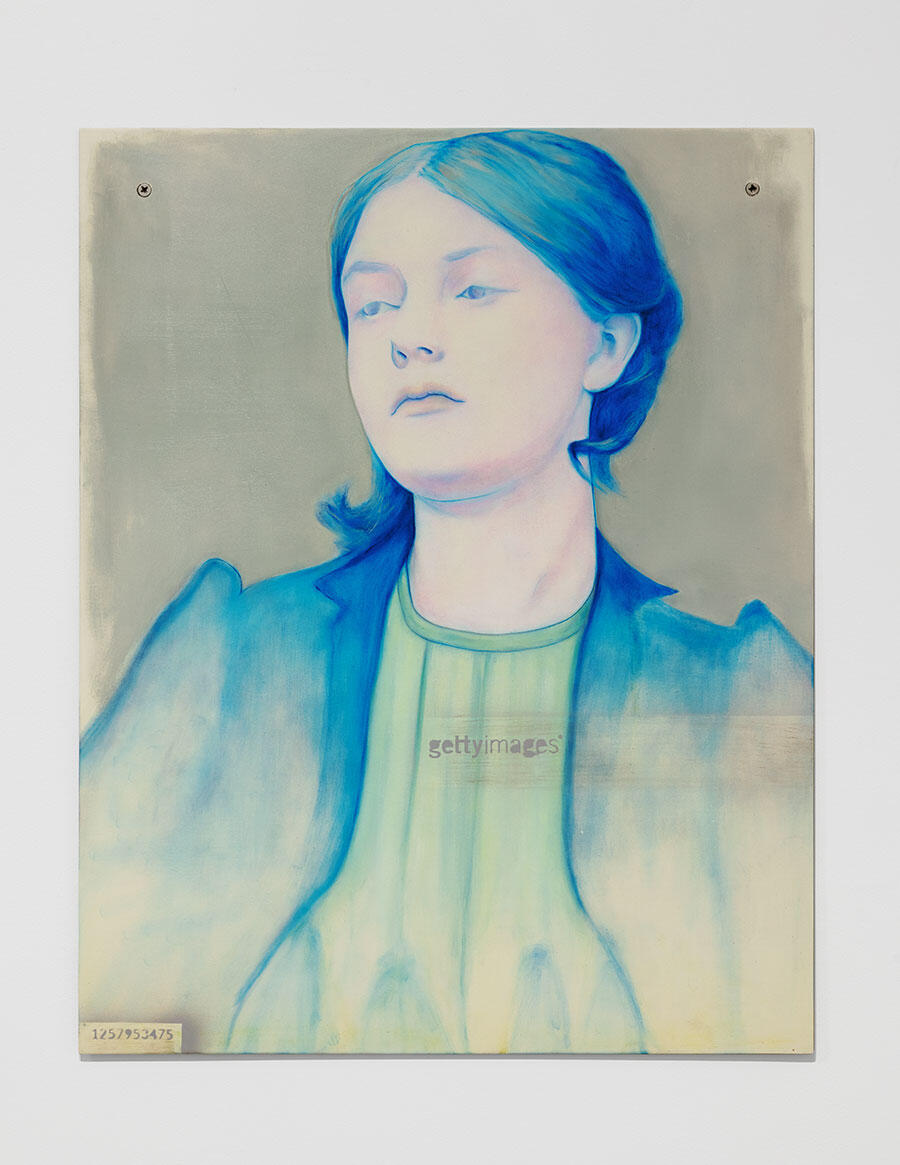

The mugshot is a genre of photography that imitates the portrait, inverting the originating scene of recognition into a printed handout that can then be used for purposes of identification, circumscription, news or entertainment. It stages a scene that is reduced to the registration of sin; it screws the ‘criminal’ into the historical record and traffics it into the world by way of an image licence. The genre is a natural extension for Lipp and since 2019 has become an ongoing motif in his work. ‘Camp as Paradigm’, an exhibition at Toronto’s Bonny Poon / Conditions in 2024, included historical photographs, again pulled from Getty Images, of several unnamed individuals who were likely among the first seated subjects of Alphonse Bertillon, the 19th-century French police officer and criminologist who invented the modern mugshot: 29 years. Day laborer. Anarchist. Vagabond (2024), reads the title of one work. Another, 19 years. Sculptor. Criminal association (2024), depicts a woman who deigns to turn her head and look away from the camera. She breaks from the frontal, anthropometric posture authorities would likely have instructed her to take, refusing, however slightly, the part of ‘criminal.’

In his book Notes on the Cinematographer (1975), film director Robert Bresson rejects the flesh-and-blood theatrics of the stage show in order to develop a theory of the elemental components that give soul to the flat, mediated flicker of the cinematic frame. He writes of the derisive attitude he holds towards ‘acting’ and to the category of ‘actors’, favouring instead the drained expressions of non-professionals, whom he calls ‘working models, taken from life’. He instructs the cinematographer to ‘Reduce to the minimum share [the model’s] consciousness […] Tighten the meshing within which he cannot any longer not be him and where he can now do nothing that is not useful.’ I could not help but think of Bresson’s non-actors while speaking to Lipp about his in-progress works which, rather than taking found images as their source, emerged from a series of in-studio photo shoots with a cast of hired models. One painting is of a man whom the artist cruised on the street and invited up to his studio: ‘He’s from Flint, Michigan, and I didn’t realize it at the time, but he was a drifter,’ he says. Several other models were cast by Lipp’s boyfriend. For each, Lipp provided his actors with a slim sketch to work from – so as to retain the rich ambiguity, perhaps, of the young sculptor and criminal associate of his earlier works. ‘I want to be the renderer and have the models act as if they were actors in a script,’ Lipp tells me, using the scene of his studio as a place for his models to rehearse any number of gestures or approximations rather than fix themselves to a ‘role’ for some kind of final take. (Once again, Bresson: ‘Model. Two mobile eyes in a mobile head, itself on a mobile body.’)

Freed from whatever arbitrary confines might limit a director to the specifics of instruction, and actors to some prefigured understanding of character, the scene I imagine taking place reduces both to something more elemental, like the light that’s used in any film or photograph to emphasize the surface effects of a setting, and where the expressions of people might start to resemble the blankness of a wall, prop or fixture. ‘I want to perform the idea of making content,’ suggests the painter, who, from where I’m looking, longs to stand in where an actor might, too.

'Sam Lipp’ is on view at Soft Opening, London, until 1 March

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Sam Lipp’

Main image: Sam Lipp, Cruelty (detail), 2014, acrylic on linen, 58 × 79 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Derosia, New York