Amy Sillman Returns to Her MoMA Show ‘The Shape of Shape’

The artist and curator reflects on the making of a form-defining exhibition, which lends its title to a new suite of columns in our January issue

The artist and curator reflects on the making of a form-defining exhibition, which lends its title to a new suite of columns in our January issue

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 256, ‘The Shape of Shape’

Jenny Harris Let’s talk about ‘The Shape of Shape’, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA], New York, in 2019.

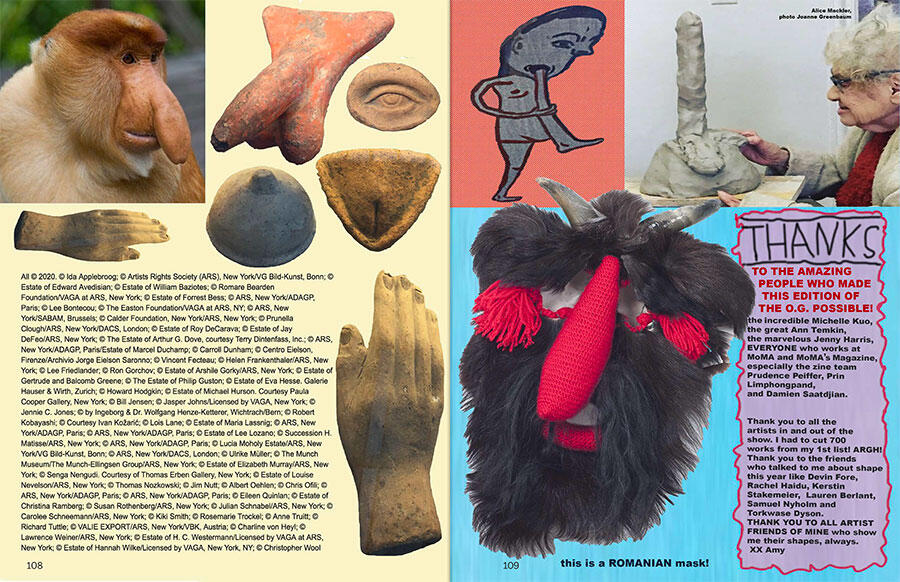

Amy Sillman Sure! I’d gotten a call from Ann Temkin [chief curator of Painting and Sculpture] and Michelle Kuo [chief curator at large], inviting me to curate an ‘Artist’s Choice’ exhibition at MoMA, drawing on the museum’s collection. In response, I suggested a show about shape. It was a kind of provocation – I felt like they’d never do it. Shape is so basic. But amazingly, they were interested! The lead time was short. I had to leave New York in three weeks to teach in Germany for the summer. But Ann said, ‘Give it a try; if it doesn’t work out, it’s okay.’ The show would take place in the autumn as part of MoMA’s reopening after years of renovation, so it was a big deal.

We worked like maniacs during our ‘trial balloon’ period: you and Michelle sending lists of works to peruse, me refining my idea, all of us working on the room and the design. Then I left for two months, and MoMA did the heavy lifting, building out the space. (Except, while in Frankfurt, I painted a huge canvas on my office floor, with a giant red shape, to use at the entrance to the show on a floor-to-ceiling, cloth-covered wall. But we never said who made it!)

JH We wanted to do something that messed with the logic of the floor’s other galleries. It was a perfect way of getting at some of the goals of the collection reinstallation – telling new stories, tracing multiple strands of modernism – but through the eyes of an artist.

AS The problem was, I realized, everything in the world is a shape: it’s just too vast a category. After earmarking 800 works the first week, I had to cut it down to 80! So, I made up rules for narrowing, like no nameable shapes.

JH No circles or squares.

AS And then I narrowed the concept of ‘shape’ to ‘shadow’.

JH How did shadow help you narrow it down?

AS Shadow implies subjectivity; point of view from the body and specific subject positions. That allowed for a kind of Trojan horse because really, underneath, the show was about the persistence of drawing, subjectivity and composition, and the fact that all kinds of things are being done all the time.

JH Could you say more about what these ‘compositional’ modes of making might have to do with traditional lineages of modernism?

AS In a way, that was precisely the origin point of the whole show: to not go by the ‘traditional lineages’ and get it exactly wrong. Let’s look at form, composition, drawing, painterly painting, easel painting, at what has been left out, people who have been overlooked, and put things in ways that might even seem wrong or embarrassing. Let’s look at art unofficially.

I partly went by my own sense of humour. That’s a form of thinking.

The show was deeply hybrid and non-teleological, and as an artist-curator, I didn’t have to adhere to a specific MoMA or modernist ‘truth claim’, so there were puns, jokes, chains of association about formal affinities that made something look good or funny or interesting next to something else. An art historian might complain that it was wrong, but it was a joy to put form next to other form and just see what happens. Tons of people are doing things that the avant-garde says you’re not supposed to be doing, just making something completely unaccountable. So, I partly went by my own sense of humour. I think that’s a form of thinking.

JH Is that part of the usefulness of shadow and subjectivity for you?

AS Subjectivity is part of any kind of art, including a dry seriality – it’s not like I need expressionist Sturm und Drang. The ‘feeling’ of a Sol LeWitt can be as moving as a tear-jerker. I recently went to Martin Barré’s Paris apartment, a painter I never really got, and when I saw the way he designed his kitchen cabinets, I grasped his work immediately. It was very intimate, the way his kitchen cabinets were organized as these small containers going around a room. It was just like his paintings.

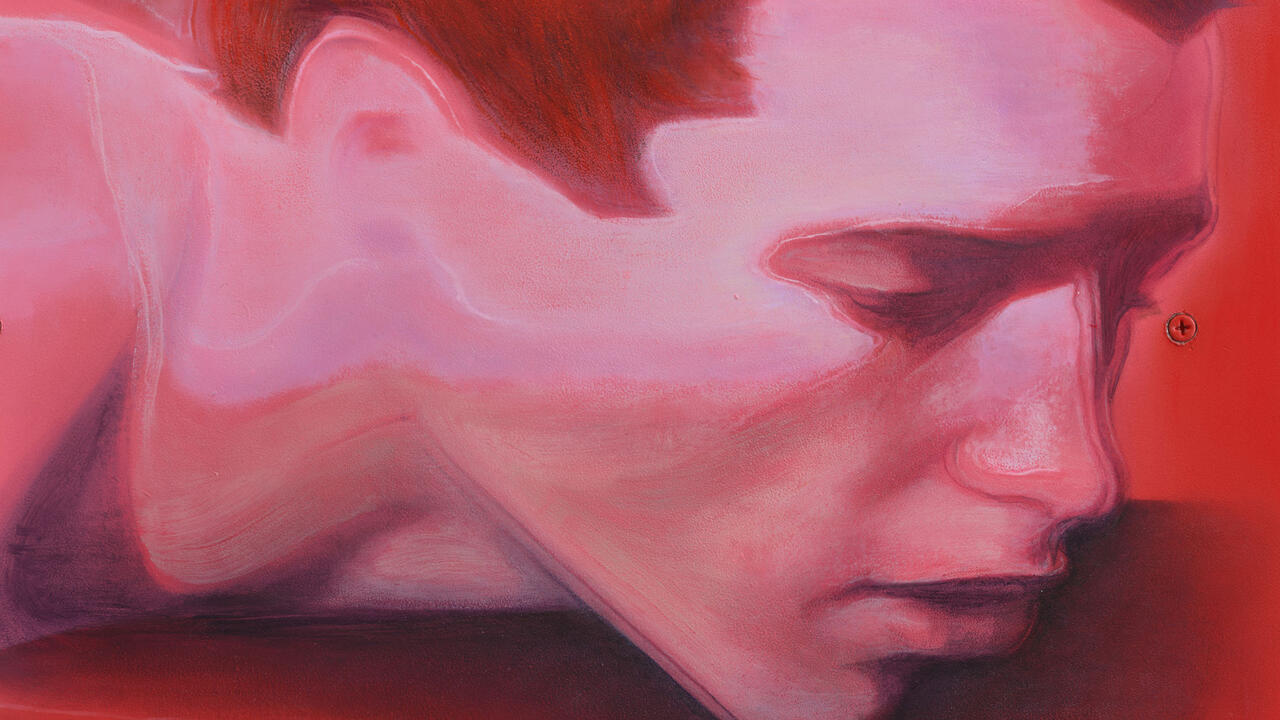

JH Your exhibitions in Switzerland and Germany [in 2024–25] seemed to be an elaboration of what you started at MoMA.

AS This was a solo show, ‘Oh, Clock!’, that opened at Kunstmuseum Bern and travelled to the Ludwig Forum in Aachen. It focused on how painting might be called a time-based process, and how in drawings, prints and animations you can see all the moments unfurled and laid bare, instead of compressed into layers as in a painting. In both venues, I also curated a show from that museum’s collection, which I hung on walls I painted by hand. The walls were loud, improvisationally made, even a bit vulgar!

JH Because of how they took up space or because of the painting?

AS Both. In Aachen, for example, we hung the museum work on these giant walls on wheels, shoved at angles into the doorways of this neat Bauhaus building.

JH What does that breaking of the logic of the modernist cube do to the physical, embodied experience of viewing?

AS It’s very destabilizing and against the architecture. It’s disruptive. And these walls will eventually be painted out and erased.

JH What was the relationship between the processes of selecting works for your solo show and works from the museum collections?

AS The selection process for my solo show was based specifically on the way my work explores time. But all three museum shows [MoMA, Bern and Aachen] were like pointing a strange flashlight into a collection in a way had not been intended. At MoMA it was, as I said, a kind of antithesis to classical modernism. In Bern, it was about foregrounding both women artists and a kind of awkwardness, going against the grain of a centuries-old Swiss museum. In Aachen, I used the protocols of my own work to look through their collection.

JH What do you mean by ‘protocols’?

AS Well, in my own paintings I use specific focal points at specific times, like colour, pattern or anthropomorphism, or negation.

JH How did you approach painting the walls in relation to your selections?

AS After choosing the collection work, I just painted freestyle, without ever looking at the collections again. I did it in situ in both Bern and Aachen.

JH What was it like to make paintings that were essentially backdrops for other people’s work?

AS It was great! But the trick for each show was to hang it exactly right, or exactly wrong!

JH What do you mean?

AS I was making moves and countermoves, beautiful sync-ups and then contradictions. It was exciting, exactly like constructing a painting is. For example, one day I painted a long wall with colours and shapes in sequence – green, yellow and pink in a row. Then I found this perfect little yellow and pink Etel Adnan painting and a blue Sophie Taeuber-Arp work that looked gorgeous against the yellow, and then a long, skinny, brown Lee Krasner that was great on the pink and green border.

JH The installation itself became part of the painting process.

AS Absolutely! It was like making a crossword puzzle from scratch.

JH How do you approach the subject of temporality? You’ve spoken before about the invisible stages that go into the making of your paintings, and that’s something you foregrounded in the survey part of the show.

AS I always think about sequence. On the macro level, the way meaning emerges as you perambulate through a gallery. On the micro level, the whole hidden drama of making a painting that is invisible once the painting is done. Like reading a novel, you don’t ‘remember’ each page – at the end it all dissolves into a kind of overall resonance. Disappearance is part of time and experience.

JH These exhibitions, in fact, disappear.

AS Yes because the walls will all be painted over.

JH Does shape give you a way of superseding any one medium? Does it create a logic or a mode of thinking across painting, drawing, animation and printmaking?

AS Not really, but I’m always thinking about more than one medium leaking into another. I’m also always thinking a-chronologically, as artists do.

JH Shape plus shadow. I suppose this is how the show ultimately changed our view of art history. You produced new and surprising genealogies of the present.

AS And you helped! It’s necessary to say no to dogma and to look at what people are really doing. I’m mostly interested in the idea of change.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 256 with the headline ‘Art, Unofficially’

Main image: Amy Sillman, ‘Oh, Clock!’ (detail), 2024–25, exhibition view at Kunstmuseum Bern. Courtesy: the artist and Kunstmuseum Bern; photograph: Annik Wetter