Constellation Cartography: Bouchra Khalili Maps Resistance

Through ‘The Mapping Journey Project’, the artist redefines Mediterranean geography, through stories of revolution and decolonization

Through ‘The Mapping Journey Project’, the artist redefines Mediterranean geography, through stories of revolution and decolonization

This piece appears in the columns section of frieze 252, ‘Remapping’

Marko Gluhaich After completing ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ [2008–11] – a series of videos documenting eight individuals’ migratory routes around the Mediterranean – you created ‘Constellations’ [2011], a corresponding series of silkscreen prints that reproduced those same mapped-out routes as astrological constellations. Could you tell me about the origins of your thinking through this concept and how it’s developed since you first introduced it into your practice?

Bouchra Khalili I have always been fascinated by geographical atlases and astronomy. The first book I remember reading was a history of geography during the Islamic Golden Age, which also covered astronomy and botany. I’ve often mentioned the influence of the Tabula Rogeriana, created by the Moroccan cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi in the 12th century, which was the most comprehensive atlas of the known world at the time. There is a map of the Mediterranean attributed to him that depicts the region ‘upside down’: what we consider the North is placed in the South, and vice versa. I’ve never forgotten that map and, when I became an artist, it remained a central reference in my work.

But my relationship with astronomy is also conceptual, even methodological. I can’t think of a project without ‘projecting’ a constellation: I first see fragments, then draw lines and, from there, connections emerge. This process is literally how the works you mention were created. One piece even forms a discourse on method: The Tempest Society [2017], in which we see the young protagonists begin by creating connections between different fragments of suppressed histories of resistance. By the end, they stand before a blackboard, drawing a constellation in real time – the visual translation of the story they’ve conveyed for nearly 55 minutes. From this perspective, The Tempest Society can be understood as the creation of trans-historical and trans-geographical constellations, with the constellation itself acting as a metaphor for a community yet to come. For me, the constellation is both the manifestation of the oldest stories and the image of becoming.

Thinking with and through constellations is also how I approach montage – film editing – as a conceptual practice and a technique for storytelling. The goal is not to produce a ‘narrative’ but to create connections, acknowledging that the lines are not straight and that gaps exist. In this sense, the gaps are integral to the larger picture. And this approach translates into the exhibition space: there is no fixed entry point. The constellation is constantly in flux.

MG In a 2018 conversation with the curator Omar Berrada, you emphasize that ‘to reduce “The Mapping Journey Project” to a work about “migrations” misses its real point: it is about resisting the arbitrariness of power.’ How has this been enacted in your own work?

BK I see my practice as the creation of a single piece. This becomes especially clear in solo exhibitions, where the arrangement of the artworks both reflects my cyclical process and maintains a sense of continuity. From this perspective, ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ and The Circle [2023] – a piece produced nearly 15 years later – address the same question: How can we form communities that are free from the restrictive ideas of belonging shaped by the nation-state model?

Showing maps not only reveals the history of colonial and imperial domination, exposing its continuous legacy, but also demonstrates that these very structures can be subverted through the performance of resilience and resistance, which can be expressed with something as simple as an indelible marker or a lone voice, which gradually transforms into a collective.

The constellation is both the manifestation of the oldest stories and the image of becoming.

The Circle focuses on the presidential candidacy of an undocumented member of Al Assifa (The Tempest), a theatre troupe formed by Maghrebi factory workers in France during the 1970s, and examines the performative power of storytelling as a means to imagine alternative ways of belonging. The Tempest Society revisited the circumstances surrounding the creation of this troupe and reactivated its theatrical methods in Athens.

Ultimately, I see my work as forming a large ‘choir’, with voices coming from different places, times and languages, yet still forming part of the same transnational and trans-historical ensemble.

MG What do you see as the relationship between the gesture of drawing on the map and the narration of that journey?

BK ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ is not the only piece in which hands play a central role. They appear in nearly all of my works – including Foreign Office, Twenty-Two Hours, The Tempest Society and The Circle – often literally performing gestures of assemblage and the formation of constellations. This practice of combining metonymies, epitomized by the hands, is also related to the notions of assemblage, arrangement and re-arrangement, which are central to my oeuvre.

Hands are connected to the concept of cinematic editing, too, which I view both as a conceptual practice and a gesture of resurrection. The hands symbolize the idea that editing – as a way of rendering visible what has been erased from history or what has remained at the margins – can rise again into the present and enable us to contemplate the future. From this perspective, the presence of hands underscores that image-making, movie-making and, by extension, editing are forms of ‘manual’ labour.

MG You have mentioned in writing and interviews the significance to your practice of Édouard Glissant’s idea of the ‘right of opacity’ [from Caribbean Discourse, 1981]. Could you speak more about this concept?

BK Glissant’s writing on opacity, as well as his proposal for archipelagic thinking, invites us to challenge the dominant model of Western universalism. I believe these ideas allow us to engage in a new ‘poetics of relation’. Filmmaking is often tied to the idea of ‘transparency’ in representation. In my practice, I focus on strategies that produce ‘opacity’.

‘The Mapping Journey Project’ has often been misinterpreted as a work composed of interviews but, in fact, there were no interviews. What preceded the filming were long conversations that lasted several weeks, allowing the participants to appropriate their own stories and words, creating a sense of distance. This is reflected both in the focus on their hands and in the calm, distant quality of their ‘performances’. In most of my works, non-professional performers portray themselves and articulate a collective voice – voices of absentees from the past, as well as voices calling from the future. There’s a paradoxical presence of bodies in my works: they are made of flesh and blood, yet, at the same time, they seem absent and, in more recent works, explicitly ‘haunted’ by both the past and the future. In that form of ‘distanciation’, opacity is created. From this perspective, the survivors of the perilous and torturous journeys described in ‘The Mapping Journey Project’ not only bear witness to their survival, but also to their becoming.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 252 with the headline ‘Astral Planes’

Bouchra Khalili’s ‘A Trilogy: The Tempest Society, The Circle, and The Public Storyteller’ is on view at Luma Westbau, until 18 May

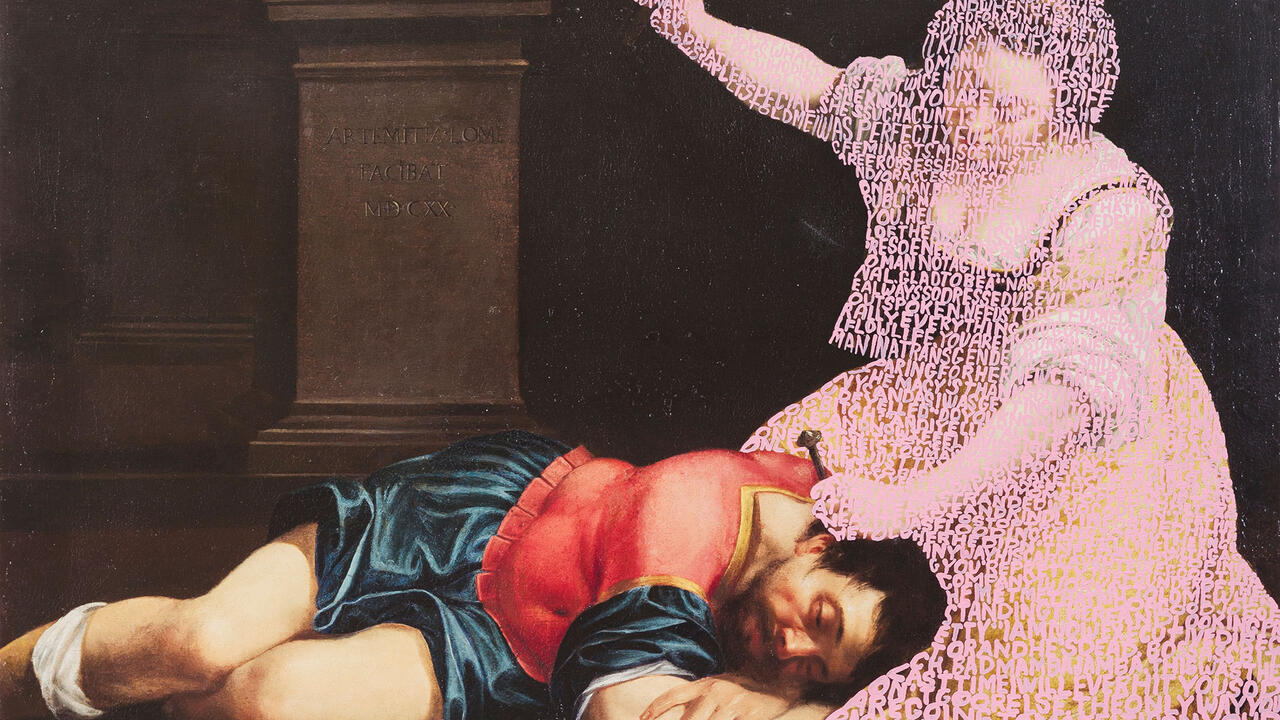

Main image: Bouchra Khalili, The Tempest Society (detail), 2017, video still. Courtesy: the artist and mor charpentier, Paris