Janine Janet

The sculptor, set-designer, window-dresser and installation artist's work as a Balenciaga artisan

The sculptor, set-designer, window-dresser and installation artist's work as a Balenciaga artisan

The sculptor, set-designer, window-dresser and installation artist Janine Janet may have explored the overlapping worlds of fashion and commercial art before Andy Warhol, Tony Duquette or Alexander McQueen, but it is her work as a Balenciaga artisan for which she is best known outside of France. A contemporary of, and designer for, Jean Cocteau, Janet’s renaissance-inspired, intramural perspective of art dovetailed closely with his own, though she no more stood in his shadow than she did in Cristobál Balenciaga’s.

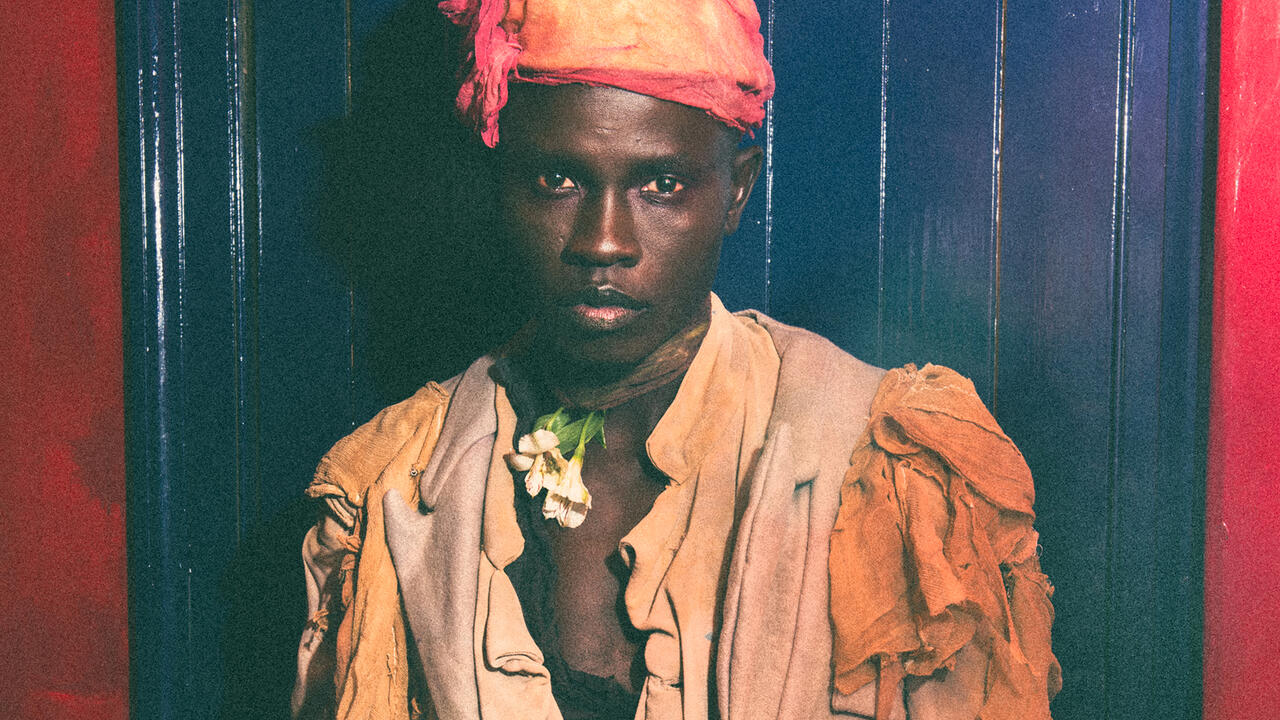

In this photograph, taken in 1962, Janet’s sculpture, La Reina (The Queen, 1959), sits in one of the three shop windows of Balenciaga’s Parisian atelier on Avenue George V, accompanied by a model wearing the Basque master’s couture egg coat, a design conceived in 1960. As with Janet’s most recognizable pieces, La Reina is decorative as well as gestural, composed of wood, nails, feathers, straw, shell and bark – an elemental nod, she claimed, to her African heritage. Born on the small French island of Reunion, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, the young Creole artist first encountered her patron one evening in 1952 when, assigned by Balenciaga directrice, Renée Tamisier, to design a window with droopy ostrich plumes, she complained to a passerby of the sorry state of her materials. The stranger introduced himself as the one-and-only Balenciaga and instructed her to demand whatever she required from the house. For decades, Janet created seasonal, window fantasias at the atelier, alongside vitrines for Hermès, Dior and Givenchy, with only one stipulation: nothing from inside the store could appear in the window as advertisement.

Though an artist whose medium was predominantly still life, Janet produced sculptural work that always intertwined with the emotive effects of performance and environment. Hired to create the costumes and set designs for Cocteau’s Le Testament d’Orphée (Testament of Orpheus, 1960), Janet found her exotic sphinx and centaurs exhibited for the first time in the world of cinema. Often, she would include perfumes and bouquets as part of her works to engage not only the haptic and visual, but the olfactory as well. At a Korrigan Lesur textile warehouse, she impressed a visiting Queen Elizabeth II with a life-sized, mock orchestra in mid-performance – instruments and all – made solely of discarded fabric. Inspired by the watery cosmogony of her childhood, she occasionally created decorative grottos for bathrooms and claimed her ambition was to design ‘functional sculpture’ for swimming pools. Treading the fine line between décor, couture and high-art at the end of the 20th century, Janet proved to be a multimedia artist avant la lettre.